The priests of the temple cults understood this but their function was to honor and care for their particular deity and ensure a reciprocity between that god and the people. The priests or priestesses, therefore, would not invoke Heka directly because he was already present in the power of the deity they served.

Magic in religious practice took the form of establishing what was already known about the gods and how the world worked. In the words of Egyptologist Jan Assman, the rituals of the temple “predominantly aimed at maintenance and stability” Egyptologist Margaret Bunson clarifies:

The main function of priests appears to have remained constant; they kept the temple and sanctuary areas pure, conducted the cultic rituals and observances, and performed the great festival ceremonies for the public.

In their role as defenders of the faith, they were also expected to be able to display the power of their god against those of any other nation. A famous example of this is given in the biblical book of Exodus (7:10-12) when Moses and Aaron confront the Egyptian “wise men and sorcerors”.

The priest was the intermediary between the gods and the people but, in daily life, individuals could commune with the gods through their own private practices. Whatever other duties the priest engaged in, as Assman points out, his primary importance was in imparting to people theological meaning through mythological narratives. They might offer counsel or advice or material goods but, in cases of sickness or injury or mental illness, another professional was consulted: the physician.

Magic & Medicine

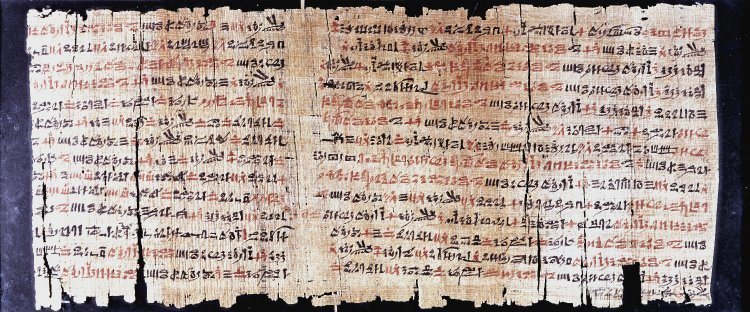

Heka was the god of medicine as well as magic and for good reason: the two were considered equally important by medical professionals. There was a kind of doctor with the title of swnw (general practitioner) and another known as a sau (magical practitioner) denoting their respective areas of expertise but magic was widely used by both. Doctors operated out of an institution known as the Per-Ankh (“The House of Life”), a part of a temple where medical texts were written, copied, studied, and discussed.

The medical texts of ancient Egypt contain spells as well as what one today would consider ‘practical measures’ in treating disease and injury. Disease was considered supernatural in origin throughout Egypt’s history even though the architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) had written medical treatises explaining that disease could occur naturally and was not necessarily a punishment sent by the gods.

The priest-physician-magician would carefully examine and question a patient to determine the nature of the problem and would then invoke whatever god seemed most appropriate to deal with it. Disease was a disruption of the natural order and so, unlike the role of the temple priest who maintained the people’s belief in the gods through standard rituals, the physician was dealing with powerful and unpredictable forces which had to be summoned and controlled expertly.

Doctors, even in rural villages, were expensive and so people often sought medical assistance from someone who might have once worked with a doctor or had acquired some medical knowledge in some other way. These individuals seem to have regularly set broken bones or prescribed herbal remedies but would not have been thought authorized to invoke a spell for healing. That would have been the official view on the subject, however; it seems a number of people who were not considered doctors still practiced medicine of a sort through magical means.

Magic in Daily Life

Among these were the seers, wise women who could see the future and were also instrumental in healing. Egyptologist Rosalie David notes how, “it has been suggested that such seers may have been a regular aspect of practical religion in the New Kingdom and possibly even in earlier times” (281). Seers could help women conceive, interpret dreams, and prescribed herbal remedies for diseases. Although the majority of Egyptians were illiterate, it seems some people – like the seers – could memorize spells read to them for later use.

Egyptians of every social class from the king to the peasant believed in and relied upon magic in their daily lives. Evidence for this practice comes from the number of amulets and charms found through excavations, inscriptions on obelisks, monuments, palaces, and temples, tomb engravings, personal and official correspondence, inscriptions, and gravegoods. Rosalie David explains that “magic had been given by the gods to mankind as a means of self-defense and this could be exercised by the king or by magicians who effectively took on the role of the gods” (283). When a king, magician, or doctor was unavailable, however, everyday people performed their own rituals.

Charms and spells were used to increase fertility, for luck in business, for improved health, and also to curse an enemy. One’s name was considered one’s identity but Egyptians believed that everyone also had a secret name (the ren) which only the individual and the gods knew. To discover one’s secret name was to gain power over them. Even if one could not discover another person’s ren they could still exercise control by slandering the person’s name or even erasing that person’s name from history.