Egyptian burial is the common term for the ancient Egyptian funerary rituals concerning death and the soul’s journey to the afterlife. Eternity, according to scholar Margaret Bunson, “was the common destination of each man, woman and child in Egypt” (87) but not `eternity’ as in an afterlife above the clouds but, rather, an eternal Egypt which mirrored one’s life on earth. The afterlife for the ancient Egyptians was The Field of Reeds (Aaru) which was a perfect reflection of the life one had lived on earth. Everything one thought had been lost at death was waiting in an idealized form in the afterlife and one’s earthly goods, interred with one’s corpse, followed suit and were there at hand.

Egyptian burial rites were practiced as early as the Pre-Dynastic Period (c. 6000-c.3150 BCE) and reflect this vision of eternity. The earliest preserved body from a tomb is that of so-called `Ginger’, discovered in Gebelein, Egypt, and dated to 3400 BCE, which contained grave goods for the afterlife. Burial rites changed over time between the Pre-Dynastic Period and the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE, the last Egyptian era before it became a Roman province) but the constant focus was on eternal life and the certainty of personal existence beyond death. This belief became well-known throughout the ancient world via cultural transmission through trade (notably by way of the Silk Road) and came to influence other civilizations and religions. It is thought to have served as an inspiration for the Christian vision of heaven and a major influence on burial practices in other cultures.

Mourning and the Soul

According to Herodotus (484-425/413 BCE), the Egyptian rites concerning burial were very dramatic in mourning the dead even though it was hoped that the deceased would find bliss in an eternal land beyond the grave. He writes:

As regards mourning and funerals, when a distinguished man dies, all the women of the household plaster their heads and faces with mud, then, leaving the body indoors, perambulate the town with the dead man’s relatives, their dresses fastened with a girdle, and beat their bared breasts. The men too, for their part, follow the same procedure, wearing a girdle and beating themselves like the women. The ceremony over, they take the body to be mummified.

Mummification was practiced in Egypt as early as 3500 BCE and is thought to have been suggested by the preservation of corpses buried in the arid sand. The Egyptian concept of the soul – which may have developed quite early – dictated that there needed to be a preserved body on the earth in order for the soul to have hope of an eternal life. The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts:

- Khat was the physical body

- Ka was one’s double-form

- Ba was a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens

- Shuyet was the shadow self

- Akh the immortal, transformed self

- Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh

- Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil

- Ren was one’s secret name

The Khat needed to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and so the body had to be preserved as intact as possible.

After a person had died, the family would bring the body of the deceased to the embalmers where the professionals “produce specimen models in wood, graded in quality. They ask which of the three is required, and the family of the dead, having agreed upon a price, leave the embalmers to their task” (Ikram, 53). There were three levels of quality and corresponding price in Egyptian burial and the professional embalmers would offer all three choices to the bereaved. According to Herodotus: “The best and most expensive kind is said to represent [Osiris], the next best is somewhat inferior and cheaper, while the third is cheapest of all” (Nardo, 110).

Types of Mummification

These three choices in burial dictated the kind of coffin one would be buried in, the funerary rites available and, also, the treatment of the body. According to the scholar Salima Ikram:

The key ingredient in the mummification was natron, or netjry, divine salt. It is a mixture of sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, sodium sulphate and sodium chloride that occurs naturally in Egypt, most commonly in the Wadi Natrun some sixty four kilometres northwest of Cairo. It has desiccating and defatting properties and was the preferred desiccant, although common salt was also used in more economical burials.

The body of the deceased, in the most expensive type of burial, was laid out on a table and the brain removed

via the nostrils with an iron hook, and what cannot be reached with the hook is washed out with drugs; next the flank is opened with a flint knife and the whole contents of the abdomen removed; the cavity is then thoroughly cleaned and washed out, firstly with palm wine and again with an infusion of ground spices. After that it is filled with pure myrrh, cassia, and every other aromatic substance, excepting frankincense, and sewn up again, after which the body is placed in natron, covered entirely over for seventy days – never longer. When this period is over, the body is washed and then wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum, which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue. In this condition the body is given back to the family who have a wooden case made, shaped like a human figure, into which it is put.

The second most expensive burial differed from the first in that less care was given to the body.

No incision is made and the intestines are not removed, but oil of cedar is injected with a syringe into the body through the anus which is afterwards stopped up to prevent the liquid from escaping. The body is then cured in natron for the prescribed number of days, on the last of which the oil is drained off. The effect is so powerful that as it leaves the body it brings with it the viscera in a liquid state and, as the flesh has been dissolved by the natron, nothing of the body is left but the skin and bones. After this treatment, it is returned to the family without further attention.

The third, and cheapest, method of embalming was “simply to wash out the intestines and keep the body for seventy days in natron” (Ikram, 54, citing Herodotus). The internal organs were removed in order to help preserve the corpse but, because it was believed the deceased would still need them, the viscera were placed in canopic jars to be sealed in the tomb. Only the heart was left inside the body as it was thought to contain the Ab aspect of the soul.

Funerals and Graves

Even the poorest Egyptian was given some kind of ceremony as it was thought that, if the deceased were not properly buried, the soul would return in the form of a ghost to haunt the living. Ghosts were considered a very real and serious threat and grieving families were often hard-pressed to afford the kind of funerary rites which the morticians advertised as the best in keeping the soul of the deceased happy and the surviving family members ghost-free.

As mummification could be very expensive, the poor gave their used clothing to the embalmers to be used in wrapping the corpse. This gave rise to the phrase “The Linen of Yesterday” alluding to death. “The poor could not afford new linens, and so wrapped their beloved corpses in those of `yesterday’” (Bunson, 146). In time, the phrase came to be applied to anyone who had died and was used by the Kites of Nephthys (the professional female mourners at funerals) in their lamentations. Bunson notes, “The deceased is addressed by these mourners as one who dressed in fine linen but now sleeps in the `linen of yesterday’. That image alluded to the fact that life upon the earth became `yesterday’ to the dead” (146). The linen bandages were also known as The Tresses of Nephthys after that goddess, the twin sister of Isis, became associated with death and the afterlife. The poor were buried in simple graves with those artifacts they had enjoyed in life or whatever objects the family could afford to part with.

Every grave contained some sort of provision for the afterlife. Tombs in Egypt were originally simple graves dug into the earth which then developed into the rectangular mastabas, more ornate graves built of mud brick. Mastabas eventually advanced in form to become the structures known as `step pyramids’ and those then became `true pyramids’. These tombs became increasingly important as Egyptian civilization advanced in that they would be the eternal resting place of the Khat and that physical form needed to be protected from grave robbers and the elements.

The coffin, or sarcophagus, was also securely constructed for the purposes of both symbolic and practical protection of the corpse. The line of hieroglyphics which run vertically down the back of a sarcophagus represent the backbone of the deceased and was thought to provide strength to the mummy in rising to eat and drink. Instructions for the deceased were written inside the sarcophagus and are now referred to as the Coffin Texts (in use c. 2134-2040 BCE) which developed from the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300 BCE). These texts would eventually be developed further during the New Kingdom (c.1570-c. 1069 BCE) as The Egyptian Book of the Dead (known to Egyptians as The Book of Coming Forth by Day, c. 1550-1070 BCE). All of these texts served to remind the soul of who they had been in life, where they were now, and how to proceed in the afterlife. The Egyptian Book of the Dead was the most comprehensive of the three, instructing how to navigate in the afterlife down to the most minute detail.

Provisioning the tomb, of course, relied upon one’s personal wealth but among the artifacts everyone wanted included were shabti dolls. In life, the Egyptians were called upon to donate a certain amount of their time every year to public building projects like the pyramids, parks, or temples. If one were ill, or could not afford the time, one could send a replacement worker. One could only do this once in a year or else face punishment for avoidance of civic duty. In death, it was thought, people would still have to perform this same sort of service (as the afterlife was simply a continuation of the earthly one) and so shabti dolls were placed in the tomb to serve as one’s replacement worker when called upon by the god Osiris for service. The more shabti dolls found in a tomb, the greater the wealth of the one buried there. As on earth, each shabti could only be used once as a replacement and so more dolls were to be desired than less and this demand created an industry to manufacture them. Most shabti dolls were made of wood but those for a pharaoh could be made of precious stone or metals.

Once the corpse had been mummified and the tomb prepared, the funeral was held in which the life of the deceased was honored and the loss mourned. Even if the deceased had been popular, with no shortage of mourners, the funeral procession and burial was accompanied by Kites of Nephthys (always women) who were paid to lament loudly throughout the proceedings. They sang The Lamentation of Isis and Nephthys, which originated in the myth of the two sisters weeping over the death of Osiris, and were supposed to inspire others at the funeral to an emotional release which would help them express their grief. As in other ancient cultures, remembrance of the dead ensured their continued existence in the afterlife and a great showing of grief at a funeral was thought to have echoes in the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Osiris) where the soul of the departed was heading.

From the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) on, the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony was performed either before the funeral procession or just prior to placing the mummy in the tomb. This ceremony again underscores the importance of the physical body in that it was conducted in order to reanimate the corpse for continued use by the soul. A priest would recite spells as he used a ceremonial blade to touch the mouth of the corpse (so it could again breathe, eat, and drink) and the arms and legs so it could move about in the tomb. Once the body was laid to rest and the tomb sealed, other spells and prayers, such as The Litany of Osiris (or, in the case of a pharaoh, The Pyramid Texts) were recited and the deceased was then left to begin the journey to the afterlife.

Conclusion

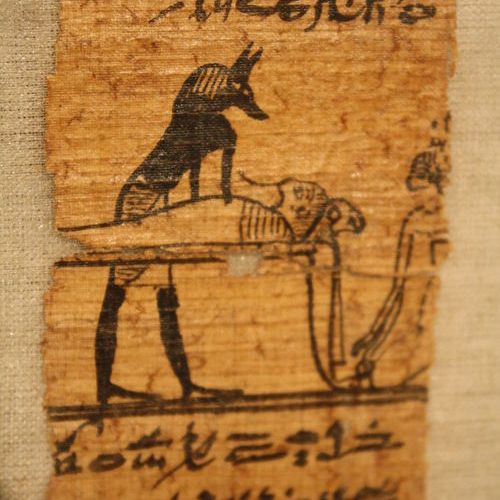

After the tomb was sealed, the mourners would celebrate the life of the departed with a feast, usually held right beside the grave. When the party was done, the people returned to their homes and resumed their lives but the soul of the departed was thought to be just starting out on the next phase of their eternal journey. The soul would wake in the tomb, be reassured and instructed by the texts on inside of the sarcophagus and walls, and rise to be guided by the god Anubis to the Hall of Truth where its heart would be weighed against the white feather of the goddess Ma’at under the supervision of Osiris and Thoth.

If one’s heart was found to be heavier than Ma’at’s feather of truth, it was dropped to the floor where it was consumed by a monster and one ceased to exist. If the heart was lighter, the soul continued on its way toward the paradise of the Field of Reeds where one would live eternally. Even if one had lived an exemplary life, however, one would not reach paradise if one’s body had not been properly buried and all the funerary rites followed in accordance with tradition. It is for this reason that proper burial rituals were so important and were so strictly observed.