To the ancient Egyptians, death was not the end of life but only the beginning of the next phase in an individual’s eternal journey. There was no word in ancient Egyptian which corresponds to the concept of “death” as usually defined, as “ceasing to live”, since death was simply a transition to another phase of one’s eternal existence. In fact, scholars claim, the modern Egyptian Arabic word for death, al mawt, is the same as ancient Egyptian and is also used for “mother”, clearly linking the death-experience with birth or, more precisely, re-birth on an eternal plane.

Once the soul had successfully passed through judgment by the god Osiris, it went on to an eternal paradise, The Field of Reeds, where everything which had been lost at death was returned and one would truly live happily ever after. Even though the Egyptian view of the afterlife was the most comforting of any ancient civilization, however, people still feared death. Even in the periods of strong central government when the king and the priests held absolute power and their view of the paradise-after-death was widely accepted, people were still afraid to die.

The rituals concerning mourning the dead never dramatically changed in all of Egypt’s history and are very similar to how people react to death today. One might think that knowing their loved one was on a journey to eternal happiness, or living in paradise, would have made the ancient Egyptians feel more at peace with death, but this is clearly not so. Inscriptions mourning the death of a beloved wife or husband or child – or pet – all express the grief of loss, how they miss the one who has died, how they hope to see them again someday in paradise – but do not express the wish to die and join them anytime soon. There are texts which express a wish to die, but this is to end the sufferings of one’s present life, not to exchange one’s mortal existence for the hope of eternal paradise.

The prevailing sentiment among these ancient Egyptian texts, in fact, is perfectly summed up by Hamlet in Shakespeare’s famous play: “The undiscovered country, from whose bourn/No traveler returns, puzzles the will/And makes us rather bear those ills we have/Than fly to others that we know not of” (III.i.79-82). The Egyptians loved life, celebrated it throughout the year, and were in no hurry to leave it even for the kind of paradise their religion promised.

The Discourse Between a Man and his Soul

A famous literary piece on this subject is known as Discourse Between a Man and his Ba (also translated as Discourse Between a Man and His Soul and The Man Who Was Weary of Life). This work, dated to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE), is a dialogue between a depressed man who can find no joy in life and his soul which encourages him to try to enjoy himself and take things easier. The man, at a number of points, complains how he should just give up and die – but at no point does he seem to think he will find a better existence on the ‘other side’ – he simply wants to end the misery he is feeling at the moment. The dialogue is often characterized as the first written work debating the benefits of suicide, but scholar William Kelly Simpson disagrees, writing:

What is presented in this text is not a debate but a psychological picture of a man depressed by the evil of life to the point of feeling unable to arrive at any acceptance of the innate goodness of existence. His inner self is, as it were, unable to be integrated and at peace. His dilemma is presented in what appears to be a dramatic monologue which illustrates his sudden changes of mood, his wavering between hope and despair, and an almost heroic effort to find strength to cope with life. It is not so much life itself which wearies the speaker as it is his own efforts to arrive at a means of coping with life’s difficulties.

As the speaker struggles to come to some kind of satisfactory conclusion, his soul attempts to guide him in the right direction of giving thanks for his life and embracing the good things the world has to offer. His soul encourages him to express gratitude for the good things he has in this life and to stop thinking about death because no good can come of it. To the ancient Egyptians, ingratitude was the ‘gateway sin’ which let all other sins into one’s life.

If one were grateful, then one appreciated all that one had and gave thanks to the gods; if one allowed one’s self to feel ungrateful, then this led one down a spiral into all the other sins of bitterness, depression, selfishness, pride, and negative thought. The message of the soul to the man is similar to that of the speaker in the biblical book of Ecclesiastes when he says, “God is in heaven and thou upon the earth; therefore let thy words be few” (5:2).

The man, after wishing that death would take him, seems to consider the words of the soul seriously. Toward the end of the piece, the man says, “Surely he who is yonder will be a living god/Having purged away the evil which had afflicted him…Surely he who is yonder will be one who knows all things” (142-146). The soul has the last word in the piece, assuring the man that death will come naturally in time and life should be embraced and loved in the present.

The Lay of the Harper

Another Middle Kingdom text, The Lay of the Harper, also resonates with the same theme. The Middle Kingdom is the period in Egyptian history when the vision of an eternal paradise after death was most seriously challenged in literary works. Although some have argued that this is due to a lingering cynicism following the chaos and cultural confusion of the First Intermediate Period, this claim is untenable. The First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) was simply an era lacking a strong central government, but this does not mean the civilization collapsed with the disintegration of the Old Kingdom, simply that the country experienced the natural changes in government and society which are a part of any living civilization.

The Lay of the Harper is even more closely comparable to Ecclesiastes in tone and expression as seen clearly in the refrain: “Enjoy pleasant times/And do not weary thereof/Behold, it is not given to any man to take his belongings with him/Behold, there is no one departed who will return again” (Simpson, 333). The claim that one cannot take one’s possessions into death is a direct refutation of the tradition of burying the dead with grave goods: all those items one enjoyed and used in life which would be needed in the next world.

It is entirely possible, of course, that these views were simply literary devices to make a point that one should make the most of life instead of hoping for some eternal bliss beyond death. Still, the fact that these sentiments only find this kind of expression in the Middle Kingdom suggests a significant shift in cultural focus. The most likely cause of this is a more ‘cosmopolitan’ upper class during this period, which was made possible precisely by the First Intermediate Period, which 19th- and 20th-century CE scholarship has done so much to vilify. The collapse of the Old Kingdom of Egypt empowered regional governors and led to greater freedom of expression from different areas of the country instead of conformity to a single vision of the king.

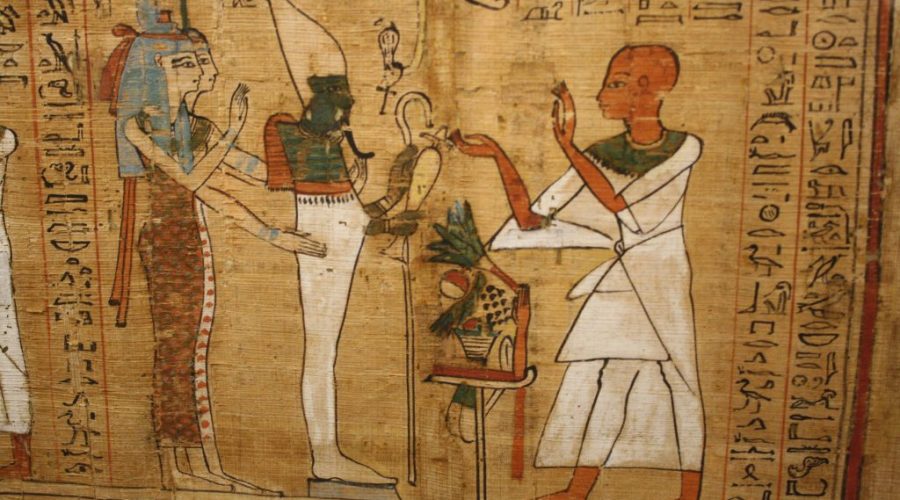

The cynicism and world-weary view of religion and the afterlife disappear after this period and New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) literature again focuses on an eternal paradise which waits beyond death. The popularity of The Book of Coming Forth by Day (better known as TheEgyptian Book of the Dead) during this period is amongst the best evidence for this belief. The Book of the Dead is an instructional manual for the soul after death, a guide to the afterlife, which a soul would need in order to reach the Field of Reeds.

Eternal Life

The reputation Ancient Egypt has acquired of being ‘death-obsessed’ is actually undeserved; the culture was obsessed with living life to its fullest. The mortuary rituals so carefully observed were intended not to glorify death but to celebrate life and ensure it continued. The dead were buried with their possessions in magnificent tombs and with elaborate rituals because the soul would live forever once it has passed through death’s doors.

While one lived, one was expected to make the most of the time and enjoy one’s self as much as one could. A love song from the New Kingdom of Egypt, one of the so-called Songs of the Orchard, expresses the Egyptian view of life perfectly. In the following lines, a sycamore tree in the orchard speaks to one of the young women who planted it when she was a little girl:

Give heed! Have them come bearing their equipment,

Bringing every kind of beer, all sorts of bread in abundance

Vegetables, strong drink of yesterday and today,

And all kinds of fruit for enjoyment.

Come and pass the day in happiness,

Tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow,

Even for three days, sitting beneath my shade.

Although one does find expressions of resentment and unhappiness in life – as in the Discourse Between a Man and his Soul – Egyptians, for the most part, loved life and embraced it fully. They did not look forward to death or dying – even though promised the most ideal afterlife – because they felt they were already living in the most perfect of worlds.

An eternal life was only worth imagining because of the joy the people found in their earthly existence. The ancient Egyptians cultivated a civilization which elevated each day to an experience in gratitude and divine transcendence and a life into an eternal journey of which one’s time in the body was only a brief interlude. Far from looking forward to or hoping for death, the Egyptians fully embraced the time they knew on earth and mourned the passing of those who were no longer participants in the great festival of life.