The government of ancient Egypt was a theocratic monarchy as the king ruled by a mandate from the gods, initially was seen as an intermediary between human beings and the divine, and was supposed to represent the gods’ will through the laws passed and policies approved. A central government in Egypt is evident by c. 3150 BCE when King Narmer unified the country, but some form of government existed prior to this date. The Scorpion Kings of the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-3150 BCE) obviously had a form of monarchial government, but exactly how it operated is not known.

Egyptologists of the 19th century CE divided the country’s history into periods in order to clarify and manage their field of study. Periods in which there was a strong central government are called ‘kingdoms’ while those in which there was disunity or no central government are called ‘intermediate periods.’ In examining Egyptian history one needs to understand that these are modern designations; the ancient Egyptians did not recognize any demarcations between time periods by these terms. Scribes of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2040-1782 BCE) might look back on the time of the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) as a “time of woe” but the period had no official name.

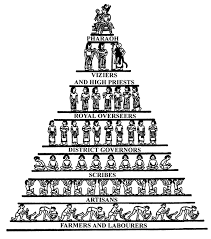

The way in which the government worked changed slightly over the centuries, but the basic pattern was set in the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3150 – c. 2890 BCE). The king ruled over the country with a vizier as second-in-command, government officials, scribes, regional governors (known as nomarchs), mayors of the town, and, following the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 – c.1570 BCE), a police force. From his palace at the capital, the king would make his pronouncements, decree laws, and commission building projects, and his word would then be implemented by the bureaucracy which became necessary to administer rule in the country. Egypt’s form of government lasted, with little modification, from c. 3150 BCE to 30 BCE when the country was annexed by Rome.

EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD & OLD KINGDOM

The ruler was known as a ‘king’ up until the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570-1069 BCE) when the term ‘pharaoh’ (meaning ‘Great House,’ a reference to the royal residence) came into use. The first king was Narmer (also known as Menes) who established a central government after uniting the country, probably by military means. The economy of Egypt was based on agriculture and used a barter system. The lower-class peasants farmed the land, gave the wheat and other produce to the noble landowner (keeping a modest portion for themselves), and the land owner then turned the produce over to the government to be used in trade or in distribution to the wider community.

Under the reign of Narmer’s successor, Hor-Aha (c. 3100-3050 BCE) an event was initiated known as Shemsu Hor (Following of Horus) which would become standard practice for later kings. The king and his retinue would travel through the country and thus make the king’s presence and power visible to his subjects. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson comments:

The Shemsu Hor would have served several purposes at once. It allowed the monarch to be a visible presence in the life of his subjects, enabled his officials to keep a close eye on everything that was happening in the country at large, implementing policies, resolving disputes, and dispensing justice; defrayed the costs of maintaining the court and removed the burden of supporting it year-round in one location; and, last but by no means least, facilitated the systematic assessment and levying of taxes. A little later, in the Second Dynasty, the court explicitly recognized the actuarial potential of the Following of Horus. Thereafter, the event was combined with a formal census of the country’s agricultural wealth

The Shemsu Hor (better known today as the Egyptian Cattle Count) became the means whereby the government assessed individual wealth and levied taxes. Each district (nome) was divided into provinces with a nomarch administering overall operation of the nome, and then lesser provincial officials, and then mayors of the towns. Rather than trust a nomarch to accurately report his wealth to the king, he and his court would travel to assess that wealth personally. The Shemsu Hor thus became an important annual (later bi-annual) event in the lives of the Egyptians and, much later, would provide Egyptologists with at least approximate reigns of the kings since the Shemsu Hor was always recorded by reign and year.

Tax collectors would follow the appraisal of the officials in the king’s retinue and collect a certain amount of produce from each nome, province, and town, which went to the central government. The government, then, would use that produce in trade. Throughout the Early Dynastic Period this system worked so well that by the time of the Third Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2670-2613 BCE) building projects requiring substantial costs and an efficient labor force were initiated, the best-known and longest-lasting being The Step Pyramid of king Djoser. During the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) the government was wealthy enough to build even larger monuments such as the pyramids at Giza.

The most powerful person in the country after the king was the vizier. There were sometimes two viziers, one for Upper and one for Lower Egypt. The vizier was the voice of the king and his representative and was usually a relative or someone very close to the monarch. The vizier managed the bureaucracy of the government and delegated the responsibilities as per the orders of the king. During the Old Kingdom, the viziers would have been in charge of the building projects as well as managing other affairs.

Toward the end of the Old Kingdom, the viziers became less vigilant as their position became more comfortable. The enormous wealth of the government was going out to these massive building projects at Giza, at Abusir, Saqqara, and Abydos and the priests who administered the temple complexes at these sites, as well as the nomarchs and provincial governors, were becoming more and more wealthy. As their wealth grew, so did their power, and as their power grew, they were less and less inclined to care very much what the king thought or what his vizier may or may not have demanded of them. The rise in the power of the priests and nomarchs meant a decline in that of the central government which, combined with other factors, brought about the collapse of the Old Kingdom.