The first standing army in Egypt was established by Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) of the 12th Dynasty in the Middle Kingdom. Prior to this time, the army was comprised of conscripts sent to the king by regional governors (called nomarchs) from their districts (nomes) who were often more loyal to their home-ruler and region than the king of the country. These early armies marched under their own banners and elevated their regional cult gods. Amenemhat I cut the power of the nomarchs by creating a professional army with a chain of command that placed power in the king’s hands and was overseen by his vizier.

The army Ahmose I mobilized against the Hyksos was made up of professionals, conscripts, and mercenaries like the Medjay warriors but under the reign of his son, Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE) this army would be extensively trained and further equipped with the best weapons available at the time. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick notes:

By the New Kingdom, the Egyptian army had begun to adopt the superior weapons and equipment of their enemies – the Syrians and Hittites. The triangular bow, the helmet, chain-mail tunics, and the Khepesh sword became standard issue. Equally, the quality of the bronze improved as the Egyptians experimented with different proportions of tin and copper.

Not only were the weapons of the army new and improved but so was the structure of the military itself. Between the time of Amenemhat I and Ahmose I the military had remained more or less the same. Weaponry and military training had improved but not dramatically. Under the reign of Amenhotep I, though, this would change as Egyptologist Margaret Bunson explains:

The army was no longer a confederation of nome levies but a first-class military force … organized into divisions, both chariot forces and infantry. Each division numbered approximately 5,000 men. These divisions carried the names of the principal deities of the nation.

Unlike the early army which went to battle under the banners of their nomes and clans, the New Kingdom army fought for the welfare of the entire country, bearing the standards of the universal gods of Egypt. The king was the commander-in-chief of the armed forces with his vizier and subordinates handling the logistics and supply lines. The chariot divisions, in which the pharaoh rode, were directly under his command and divided into squadrons with their own captain. There were also mercenary forces, like the Medjay, who served as shock troops.

The Age of Imperial Egypt

These were the troops who forged and then maintained the Egyptian Empire. Amenhotep I continued the policies of Ahmose I and each pharaoh who came after him did the same. Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) put down rebellions in Nubia and expanded Egypt’s territories in the Levant and Syria. Nubia was especially prized by the Egyptians for their gold mines and, in fact, the region took its name from the Egyptian word for ‘gold’ – nub. Little is known of his successor, Thutmose II (1492-1479 BCE) because his reign is overshadowed by the impressive era of queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE).

Hatshepsut is not only the most successful female ruler in Egypt’s history but among the most remarkable leaders of the ancient world. She broke with the tradition of a patriarchal monarchy with no evidence of rebellion on the part of her subjects or the court and established a reign which enriched Egypt financially and culturally without engaging in any extensive military campaigns.

Although there is evidence that she commissioned military expeditions early in her reign, the remainder was peaceful and focused on Egypt’s infrastructure, building projects, and trade. She re-established contact with the Land of Punt – an almost mythical land of riches – which supplied Egypt with many of the luxury goods the upper classes came to covet as well as necessary items for the worship of the gods (such as incense) and the cosmetics industry (oils and scented flowers).

When Hatshepsut died, she was succeeded by Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) who, possibly in an effort to prevent future women from emulating her, had Hatshepsut’s name erased from monuments. He would have done this in order to maintain the tradition of a male sovereign, not because he had anything against the queen, and he left her name intact inside her mortuary temple and elsewhere out of the public eye. Even so, later kings knew nothing of her accomplishments and she would not be known to history again for over 2,000 years.

Thutmose III should not be remembered for this one action, however, as he proved himself an able and efficient ruler and a brilliant military leader. Historians have often referred to him as the “Napoleon of Egypt” for his success in battle as he fought 17 campaigns in 20 years and, unlike Napoleon, he was victorious in all of them. He also encouraged and extended trade and was a man of culture who helped preserve Egypt’s history.

The foreign and domestic policies of Thutmose III enriched Egypt and expanded its borders, providing the country with a stable economy and a growing international reputation. By the time of the reign of Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE), Egypt was among the wealthiest and most powerful in the world. Amenhotep III was a brilliant administrator and diplomat whose prosperous reign established Egypt firmly in what historians refer to as the “Club of the Great Powers” – which included Babylonia, Assyria, Mittanni, and the Land of the Hatti (Hittites) – all of whom were joined in peaceful relations through trade and diplomacy.

Foreign kings wrote regularly to Amenhotep III asking for gold and favors, which he freely granted, and countries were eager to trade with Egypt because of its vast resources and considerable strength. The Egyptian army at this time was formidable and alliances were quick to be made. Wealth flowed into the royal treasury from beyond Egypt’s borders and Amenhotep III could afford to pay large crews of workers to erect his temples and monuments. He built so many of these, in fact, that later historians thought he must have ruled for over 100 years to have accomplished all he had; in reality, he was simply an exceptionally able statesman.

Amenhotep III’s son and successor was Amenhotep IV who, in the fourth or fifth year of his reign, changed his name to Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) and abolished the traditional religious practices of Egypt. Although Akhenaten is frequently depicted by modern day writers as a great religious visionary and an exceptional king he was actually neither. His religious reforms were most likely a political maneuver to decrease the power of the Cult of Amun which, by his time, was almost as powerful as the king, and his attention to rule was so minimal that his wife, Nefertiti, took over administrative duties and correspondence with other nations.

The friction between the Cult of Amun and royalty started during the period of the Old Kingdom when the kings of the 4th Dynasty elevated the sect and gave them tax-exempt status in exchange for performing the necessary mortuary rituals at the Giza complex. Since they were tax-exempt, all the produce from their lands went to them directly – not to the government – and so they were able to amass considerable wealth. From the Old Kingdom on, the cult only grew in power and so it is probable that Akhenaten’s “reforms” were motivated far more by politics and greed than any divine vision of a one true god.

Under the reign of Akhenaten, the capital was moved from Thebes to a new city, Akhetaten, designed and built by the king and dedicated to his personal god. The temples in all the cities and towns were closed and religious festivals abolished except those venerating his god, the Aten. The Egyptian economy relied heavily on religious practices as the temples were the centers of the community and employed a large staff.

Further, crafts-people who made statuary, amulets, and other religious artifacts were also put out of work. The central cultural value of Egypt – ma’at (harmony and balance) – which was the foundation of the religion and the society was ignored by Akhenaten’s administration and so were the diplomatic and commercial ties with other powers.

Akhenaten’s successor was Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE) who was in the process of restoring Egypt to its former status when he died young. His work was completed by Horemheb (1320-1295 BCE) who erased Akhenaten’s name from history and destroyed his city. Horemheb succeeded in restoring Egypt but it was nowhere near the strength it had been prior to Akhenaten’s reign.

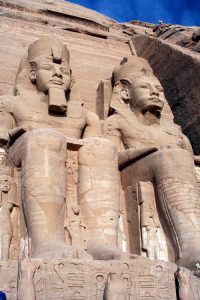

During the 19th Dynasty which followed Horemheb, the most famous pharaoh in Egypt’s history would claim to have finally restored the country to power: Ramesses II (the Great, 1279-1213 BCE). Ramesses II is not only the best-known pharaoh in the present day but also in antiquity thanks to his talent for self-promotion and the skills of his vizier, Khay, who ensured that the king’s name would endure through monuments, temples, and towering statuary honoring him.

Ramesses II may not have completely brought Egypt back to the level of power it had known under Amenhotep III but he certainly came close. He re-established ties with the other great powers, signed the first peace treaty in the world with the Hittites following the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BCE), and, although he had himself depicted regularly as a great warrior-king, concentrated most of his reign on domestic policies, trade, and diplomacy. Thutmose III was actually the most skilled military leader of the New Kingdom, not Ramesses II, but the image of the pharaoh as a mighty warrior was a long-established tradition in Egypt symbolizing the king’s powers even if a particular monarch was actually more skilled in other areas.