The Cult of Horus in Egypt, as noted, was already ancient by the time the Osiris Myth became popular and that myth elevated the worship of Osiris, Isis and Horus to a national level. The Cult of Isis became so popular that worship of the goddess traveled through tradeto Greece and then to Rome where it became the greatest challenge to the new religion of Christianity in the 3rd-5th centuries CE. Horus traveled with her in the form of Horus the Child and influenced Christian iconography of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child.

There is no doubt the woship of Isis influenced early Christianity through the concepts of the Dying and Reviving God who returns from the dead to bring life to the people, eternal life through dedication to that god, the image of the virgin mother and child, and even the red-hue and characteristics of the Christian devil. This is not to say, however, that Christianity is simply the Isis Cult re-packaged nor that Horus was the prototype for the risen Christ.

The book The Pagan Christ by Tom Harpur (2004) makes this very claim, however, and has given rise to the so-called Horus-Jesus Controversy also known as the Son of God Controversy. Harpur claims that Christianity was invented wholly from Egyptian mythology and that Jesus Christ is simply Horus re-imagined. To support his claim, Harpur cites `experts’ on the subject such as Godfrey Higgins, Gerald Massey, and Alvin Boyd Kuhn, all writers from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, none of whom were biblical scholars or Egyptologists. Higgins was an English magistrate who believed all religions came from the Lost City of Atlantis; Massey, a self-styled Egyptologist, was an English spiritualist who studied available inscriptions at the British Museum; Kuhn was a self-published author whose primary focus was promoting his Christ Myth Theory which was essentially just a re-write of the work done by Higgins and Massey.

Harpur presents these `experts’ as though they had uncovered something miraculous and unheard of when, in reality, their observations are often innacurate re-treads of earlier works (such as those of Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius) or wildly speculative theories presented as though they are brilliant insights. The Dying and Reviving God motif had existed for thousands of years before the apostle Paul began is evangelical efforts c. 42-62 CE and the concept of eternal life through personal dedication to a god was equally well established. Harpur’s book presents a number of very serious problems to any reader acquainted with the Bible, Christianity, and Egyptian Mythology and history but his most serious offense is the claim that Horus and Jesus share “remarkable similarities”.

This claim, which is quite obviously false to anyone who knows the stories of the two figures, has become the best known of the book. Unfortunately, many readers who do not know the original stories take Harpur’s claims as legitimate scholarship when they are not. To cite only a few examples, Harpur asserts that both Horus and Jesus were born in a cave – this is false, Horus was born in the Delta swamps and Jesus in a stable; both births were announced by an angel – also false, as the concept of the angel, a messenger of God, is absent from Egyptian beliefs; Horus and Jesus were both baptized – false, baptism was not practiced by Egyptians; both Horus and Jesus were tempted in the wilderness – false, Horus battled Set in many different regions, including the arid desert while the gospel stories make clear that Jesus was tempted in the desert or the wilderness; Horus and Jesus were both visited by Three Wise Men – false, Horus is never visited by wise men and, even more damaging to Harpur’s ‘scholarship’, there are not ‘three wise men’ mentioned in the Bible which only references `wise men’ who bring three kinds of gifts; Horus and Jesus both raised the dead back to life – false, Horus had nothing to do with raising Osiris or anyone else from the dead.

Horus the Redeemer

All of Harpur’s further claims are equally untenable owing to extremely poor scholarship and a reliance on sources which are not credible. Neither Horus nor Jesus benefit from his shoddy comparison of their lives. The concept of Horus as redeemer was well established in Egypt but this does not necessarily mean that concept was exclusive to him nor that there were not other `redeemers’ in between the time of the popularity of Horus and the development of Christianity. Horus was a redeemer of health and humans in their earthly form; not of souls needing salvation from sin and eternal punishment. Horus the Child was one of a number of so-called ‘child gods’ of ancient Egypt who appeared in the form known as Shed (Savior) but was a savior from earthly troubles, not eternal ones. Geraldine Pinch writes:

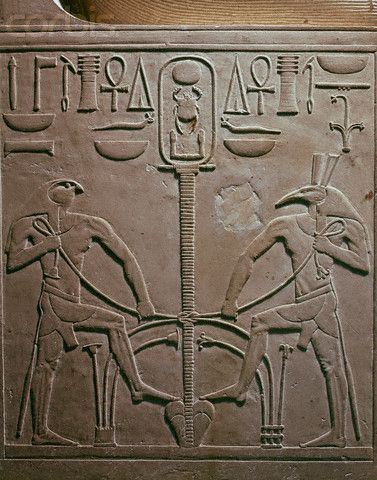

He appeared on stelae of the late New Kingdom dressed as a prince who vanquished dangerous animals with his bow or curved sword. This was a forerunner of the type of magical stela known as a cippus. On these, the naked Horus child tramples on crocodiles and squeezes the life out of other dangerous creatures such as snakes, lions, and antelopes. When the Greeks saw such objects, they identified Horus the Child/Harpocrates with the infant Herakles (Hercules) who strangled two snakes that attacked him in his cradle (147).

Horus also, through his Four Sons, watched over and was a friend to the dead but was primarily a god of the living. He was the distant god who could draw close in time of need, the dependable friend, the caring brother, the protector, and one’s guide through the perils of life. He shares these qualities and characteristics with other deities in cultures around the world up through the present day but to the Egyptians he was wholly unique because he was their own; as it is and has always been with any god of any faith anywhere.