Few ancient civilizations enabled women to achieve important social positions. In Ancient Egypt, there are not only examples indicating women high officials were not so rare, but more surprising (for its time), there are women in the highest office, that of Pharaoh. More than a kind of feminism, this is a sign of the importance of theocracy in Egyptian society.

Egyptian society of antiquity, like many other civilizations of the time, used religion as a foundation for society. This was how the throne of the power of the Pharaohs was justified, as anointed by the gods, and the holder of the throne had a divine right. Typically, in ancient societies power was transferred from one male to the next. The son inherited the power, and in cases where the king did not have a son, the throne was then inherited by the male members of the family further removed from the king, such as cousins or uncles. But even if the monarch had daughters, they could not gain power.

In Egyptian civilization, this obligation of passing power to a male successor was not without exceptions. Royal blood, a factor determined by divine legitimacy, was the unique criteria for access to the throne. However, the divine essence was transmitted to the royal spouse, as was the case with Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaton.

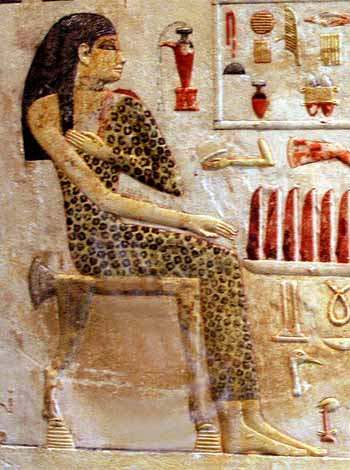

Egyptians preferred to be governed by a woman with royal blood (being divine according to mythology) rather than by a man who did not have royal blood. Also, during crises of succession, there were women who took power. When this happened, the female Pharoah adopted all of the masculine symbols of the throne. There even exist doubts, in some instances, about the sex of certain Pharoahs who could have been women.

During the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt, when Amenhotep I died, his successor Thutmose I appears to have not been his son, at least he was not the child of a secondary wife of the late Pharaoh; if his wife Ahmes was related to Amenhotep I, this union permitted divine legitimacy. For the following successor, princess Hatsepsut, daughter of Thutmose I and the Great Royal Wife, enabled Thutmose II, son of his second wife and therefore half-brother of the princess, to gain the throne by marrying him.

It was not rare for women to gain the throne in Ancient Egypt, as with Hatsepsut, who took the place of her nephew Thutmose III. When Hatsepsut inherited the throne from her late husband and became Pharaoh, her daughter Neferure took on a role that exceeded the normal duties of a royal princess, acquiring a more queenly role. There were also the Cleopatras, of whom the most well-known is Cleopatra VII (69 BCE to 30 BCE), famous for her beauty and her relationships with Julius Caesar and then Marc Antony, the leaders who depended upon her throne.