Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) is considered to be one of ancient Egypt’s most revered if controversial rulers. Celebrated by Egyptologists as a commanding female sovereign whose rule ushered in a long period of military success, economic growth and prosperity.

Hatshepsut was ancient Egypt’s first female ruler to reign with the full political authority of a pharaoh. However, in tradition-bound Egypt, no woman should have been able to ascend the throne as a pharaoh.

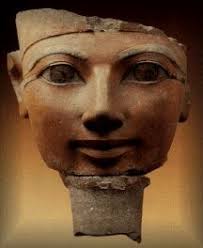

Initially, Hatshepsut’s reign began as regent to her stepson Thuthmose III (1458-1425 BCE). Around the seventh year of her reign, however, she moved to assume the throne in her own right. Hatshepsut directed her artists to depict her as a male pharaoh in reliefs and statuary while continuing to refer to herself as a woman in her inscriptions. Hatshepsut became the 18th Dynasty’s fifth pharaoh during the New Kingdom period (1570-1069 BCE) and emerged as one of Egypt’s most able and successful pharaohs.

Facts About Queen Hatshepsut

- First Queen to rule as a Pharaoh in her own right

- Rule is credited with returning Egypt to economic prosperity

- Name translates as “Foremost of Noble Women”.

- Though credited with some important military victories early in her reign, she is most remembered for returning a high level of economic prosperity to Egypt.

- As pharaoh, Hatshepsut dressed in the traditional male kilt and wore a fake beard

- Her successor, Thutmose III, attempted to erase her rule from history as a female Pharaoh was believed to disrupt Egypt’s sacred harmony and balance

- Her temple is one of the one admired in ancient Egypt and created the trend of burying pharaohs in the nearby Valley of the Kings

- Hatshepsut’s long reign saw her conduct successful military campaigns followed by a long period of peace and the reestablishment of critical trade routes.

Hatshepsut’s Lineage

Hatshepsut was Thuthmose I (1520-1492 BCE) and his Great Wife Ahmose’s daughter. Thutmose I was also the father of Thutmose II with his secondary wife Mutnofret. Adhering to the tradition amongst the Egyptian royal family, Hatshepsut married Thutmose II before she turned 20. Hatshepsut received the supreme honour open to an Egyptian woman after that of the role of the queen, when she was elevated to the position of God’s Wife of Amun at Thebes. This honour conferred more power and influence than many queens enjoyed.

God’s Wife of Amun was largely an honorary title for an upper-class woman. Its main obligation was to assist the Great Temple of Amun’s high priest. By the New Kingdom, God’s Wife of Amun enjoyed sufficient power to influence state policy. At Thebes, Amun enjoyed extensive popularity. Eventually, Amun evolved into Egypt’s creator god as well as king of their gods. Her role as Amun’s wife positioned Hatshepsut as his consort. She would have officiated at Amun’s festivals, singing and dancing for the god. These duties elevated Hatshepsut to divine status. To her, fell the duty of arousing him for his act of creation at the beginning of each festival.

Hatshepsut and Thutmose II produced a daughter Neferu-Ra. Thutmose II and his lesser wife Isis also had a son Thutmose III. Thutmose III was named as his father’s successor. While Thutmose III was still a child, Thutmose II died. Hatshepsut took on the role of regent. In this role, Hatshepsut controlled Egypt’s state affairs until Thutmose III came of age.

However, in her seventh year as regent, though, Hatshepsut assumed the throne of Egypt herself and was crowned pharaoh. Hatshepsut adopted the gamut of royal names and titles. While Hatshepsut directed she be depicted as a male king her inscriptions all adopted the feminine grammatical style.

Her inscriptions and statuary portrayed Hatshepsut in her royal magnificence dominating the foreground, while Thutmose III was positioned below or behind Hatshepsut on a diminished scale indicating Thutmose’s lesser status. While Hatshepsut continued to address her stepson as Egypt’s king, he was king only in name. Hatshepsut plainly believed she had as much claim to Egypt’s throne as any man and her portraits reinforced this belief.

Hatshepsut’s Early Reign

Hatshepsut initiated action to quickly legitimize her rule. Early in her reign, Hatshepsut married her daughter Neferu-Ra to Thutmose III, bestowing the title of God’s Wife of Amun on Neferu-Ra to assure her role. Were Hatshepsut to be forced to accede to Thutmose III, Hatshepsut would remain in an influential position as Thutmose III’s mother-in-law as well as being his stepmother. She had also elevated her daughter to one of Egypt’s most influential and prestigious. Hatshepsut further legitimized her rule by depicting herself as Amun’s daughter and wife. Hatshepsut further claimed Amun had materialised before her mother as Thutmose I and conceived her, ascribing Hatshepsut with the status of a demi-goddess.

Hatshepsut bolstered her legitimacy by depicting herself as Thutmose I’s co-ruler on reliefs and inscriptions on monuments and government buildings. Further, Hatshepsut claimed Amun had despatched an oracle to her predicting her later ascension to the throne, thus connecting Hatshepsut to the defeat of the Hyskos People 80 years previously. Hatshepsut exploited Egyptian’s memory of the Hyksos as loathed invaders and tyrants.

Hatshepsut portrayed herself as Ahmose’s direct successor, whose name Egyptian’s remembered as a great liberator. This strategy was designed to defend her against any detractors who claimed a woman was unworthy of being Pharaoh.

Her countless temple monument and inscriptions illustrated just how groundbreaking her rule was. Prior to Hatshepsut taking the throne, no woman had previously dared to openly rule Egypt as its pharaoh.

Hatshepsut As Pharaoh

As previous pharaoh’s had, Hatshepsut commissioned vast construction projects including a magnificent temple at Deir el-Bahri. On the military front, Hatshepsut dispatched military expeditions to Nubia and Syria. Some Egyptologists point to the tradition of Egyptian pharaohs being warrior-kings to explain Hatshepsut’s campaigns of conquest. These may be simply been an extension of Thutmose I’s military expeditions to emphasize the continuity her reign represented. New Kingdom pharaohs emphasised the maintenance of secure buffer zones along their frontier to avoid any repetition of a Hyksos-style invasion.

However, it was Hatshepsut’s ambitious construction projects, which absorbed much of her energy. They created employment for Egyptians during the time when the Nile flooded making agriculture impossible while honouring Egypt’s gods and reinforcing Hatshepsut’s reputation amongst her subjects. The scale of Hatshepsut’s construction projects, together with their elegant design, bore testimony to the wealth under her control coupled with the prosperity of reign.

Politically Hatshepsut’s fabled Pent expedition in today’s Somalia was the apogee of her reign. Punt had traded with Egypt since the Middle Kingdom, however, expeditions to this far off and exotic land were hideously expensive to outfit and time-consuming to mount. Hatshepsut’s ability to dispatch her own lavishly equipped expedition was yet another testament to the wealth and influence Egypt enjoyed during her reign.

Hatshepsut’s magnificent temple at Deir el-Bahri set into the cliffs outside the Valley of the Kings is one of the most impressive of Egypt’s archaeological treasures. Today it is one of Egypt’s most visited sites. Egyptian art created under her reign was delicate and nuanced. Her temple was once connected to the Nile River via a lengthy ramp rising from a courtyard dotted with small pools and groves of trees to an imposing terrace. Many of the temple’s trees appear to have been transported to the site from Punt. They represent history’s first successful mature tree transplants from one country to another. Their remains, now reduced to fossilized tree stumps, are still visible in the temple courtyard. The lower terrace was flanked with graceful decorated columns. A second equally imposing terrace was accessed via an imposing ramp, which dominated the temple layout. The temple was decorated throughout with inscriptions, reliefs and statuary. Hatshepsut’s burial chamber was cut from the cliff’s living rock, which formed the building’s back wall.

Succeeding pharaohs so admired the elegant design of Hatshepsut’s temple that they selected nearby sites for their burial. This sprawling necropolis eventually evolved into the complex we know today as the Valley of the Kings.

Following Tuthmose III’s successful suppression of another rebellion by Kadesh in c. 1457 BCE Hatshepsut effectively vanishes from our historical record. Tuthmose III succeeded Hatshepsut and had all evidence of his stepmother and her reign erased. Wreckage from some works naming her was dumped near her temple. When Champollion excavated Deir el-Bahri he rediscovered her name together with mystifying inscriptions inside her temple.

When and how Hatshepsut died remained unknown until 2006 when Egyptologist Zahi Hawass claimed to have located her mummy in the Cairo museum’s holdings. A medical examination of that mummy indicates Hatshepsut died in her fifties after developing an abscess following a tooth extraction.

Ma’at And Disturbing Balance And Harmony

For ancient Egyptians, amongst their pharaoh’s primary responsibilities was the maintenance of ma’at, which represented balance and harmony. As a woman ruling in a man’s traditional role, Hatshepsut represented a disruption to that essential balance. As the pharaoh was a role model for his people Tuthmose III potentially feared other queens might harbour ambitions to rule and view Hatshepsut as their inspiration.

Tradition held only men should rule Egypt. Women regardless of their skills and abilities were relegated to the role of consorts. This traditional reflected the Egyptian myth of the god Osiris ruling supreme with his consort Isis. Ancient Egyptian culture was conservative and highly change-averse. A female pharaoh, regardless of how successful her reign was, was outside the accepted boundaries of the role of the monarchy. Hence all memory of that female pharaoh needed to be erased.

Hatshepsut exemplified the ancient Egyptian belief that one lives for eternity as long as one’s name is remembered. Forgotten as the New Kingdom continued she remained so for centuries until her rediscovery.

Reflecting On The Past

With her rediscovery in the 19th century by Champollion, Hatshepsut regained her deserved place in Egyptian history. Flaunting tradition, Hatshepsut dared to reign in her own right as a female pharaoh and proved one of Egypt’s most outstanding pharaohs.