You might be tempted to ignore the stubby structures of frontier Aswan, known in Ancient Egypt as Swenett. You might focus on the more impressive pillars of Cairo and the temples of Giza – but there would be no pyramids and no shrines without little ol’ Aswan and the Nile River.

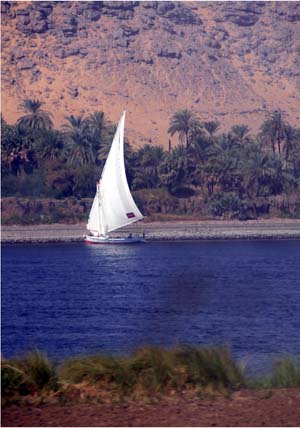

Dhow on the Nile River near Aswan

Aswan is hot. It receives essentially no rain. Ever. Daytime temperatures hover over 100 degrees six months out of twelve. The only source of water is the Nile, less than half a mile in width. But Ancient Egypt considered Aswan indispensable for its special granite, a rock called Syenite.

Rough-hewn blocks were chiseled from raw stone, loaded onto barges, and shipped down the placid Nile River to the halls of the god-king pharaohs. During flood season, this trip would take about two weeks, for there was not a single cataract to delay the trip. During the dry season, the same trip would take about two months. Ships would return bearing cargo and men, their sails fattened by northern trade winds.

The Nile River was Ancient Egypt’s highway. There were no semi-trucks, no Amazon Prime 1-day shipping offers. There was only water. No bridges spanned the Nile’s girth in ancient times. Only boats could plow the surface and skim across the channel measuring 20-40 feet deep.

Around 4,000 B.C., the Ancient Egyptians first lashed bundles of papyrus stalks together to make rafts. Later, craftsmen learned to build wooden ships using local acacia wood. Some of these boats could carry cargo up to 500 tons. That’s as much as 125 elephants! Where boats could no travel over desert sands, Egyptians rode camels from one hidden cistern to another.

Flora and Fauna of the Riverbanks

Animals

Of course, most Egyptians rarely saw the Nile from its center. The farmer of the Middle Kingdom would have stood at the water’s edge and peered across two miles of silvery blue. In the summer, those two miles might expand to five or ten. Torrential spring rains in Ethiopia and sub-Saharan Africa would cause the Egyptian Nile to overflow its banks for 4-6 months, inundating the surrounding flood plain in black silt.

The Nile River plain was a suitable living environment for a variety of animals.

The two largest herbivores are the hippopotamus and black rhinoceroses, both of which are now nearing extinction. Blue herons and white ibis birds scope out the shallow waters for small fish, eels and snakes. The Nile River contains more than 30 species of snakes, and more than half are venomous. Not for nothing did Cleopatra, the great Queen of Egypt, die from the bite of an asp.

Depictions of Snakes, Wadjet Amulet

This annual flooding cycle enticed water-loving amphibians, reptiles and birds to come dwell in the Nile. The most common reptile is the Nile crocodile, a grayish beast that grows up to 1,500 pounds. It waylays unsuspecting gazelles and small mammals who come to feed at the riverbanks.

Nile Crocodile Facts – The Nile Crocodile has been a major component of the Egyptian culture and way of life since the first Egyptians settled along the fertile banks of the Nile. Most Nile Crocodiles are approximately 4 meters in length, although some have been reported as longer.

They make their nests along the banks of the Nile River, where the female may lay up to 60 eggs at one time. Some three months later the babies are born and are taken to the water by their mother. They will remain with her for at least two years before reaching maturity.

Nile Crocodiles

Farming and Food

Although Ancient Egyptians relied on fish for animal protein, they obtained most of their food from the earth. The rich topsoil of the Nile basin can measure up to 70 feet deep. It is a farmer’s utopia. After Ahket, the season of Inundation, villages planted the first seeds.

During Peret, the growing season, which lasted October-February, farmers tended their fields. Shemu was the season of harvest and abundance. They would either carry water by hand, by camel, or would dig irrigation canals from the Nile River to water the rich black kemet of the fields.

Farmers cultivated all manner of crops: barely for beer, cotton for clothing, melons and pomegranates and figs for an evening meal. But three crops stood out: wheat, flax, and papyrus. Wheat was ground into bread, flax was spun into linen, and papyrus dried into a paper substitute.