Material Objects & Cultures

Material objects convey volumes about the people who possessed them. Cultures and societies in every generation are in part classified – either correctly or incorrectly – by the objects or symbols they select and how they are displayed. Typically, the formal study of society is the purview of anthropologists and social scientists who categorize ‘people’ into cultural assemblages which are extrapolated from commonly held ‘features’ (e.g. clothing, jewellery, and music) and their interpersonal behaviour (e.g. occupation, political activities, rand eligious practices) which socially defines them. Hence, any answer to the ‘meaning of things’ in society, generally speaking, is a structured hypothesis.

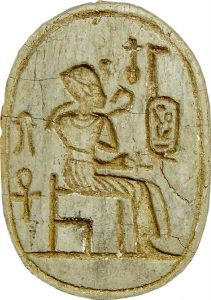

Amulets are an example of such culturally defining objects, and they satisfied a variety of roles in the society of Ancient Egypt. Specifically, they possessed complex socio-religious meanings which are reflected in their diverse designs and, therefore, may be analyzed within ontological/phenomenological and/or structural/poststructural dichotomies. In this article, I shall discuss Egyptian amulets as objects of human expression; exploring their symbolism and utilization in socio-cultural functions.

Life Before Death

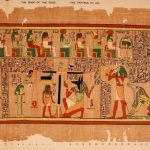

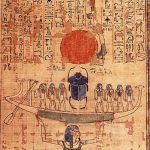

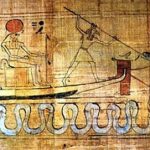

Culturally, amulets were intimately associated with the greater Egyptian religious system, which was a state system whose earliest cosmological views of nature contained a cyclical perception of life, death, and rebirth. Typically, amulets were worn as jewellery by both men and women in social settings. However, they were not worn as a mere ornamental feature or simply as a sign of religious devotion. Rather, the amulet was regarded as a talisman. That is to say – metaphysically speaking – each amulet was understood to possess a precise supernatural attribute which could be imparted to those who wore them. The spiritual value of the amulet depended entirely on what specific enchantment was assigned to it and how it was employed. For example, to increase an amulet’s potency, a sacrosanct ‘inscription’ may have been added to ascribe a certain spell. Unprovenanced specimens reveal wishes for a ‘happy new year’ or ‘health and prosperity’ and from this feature, we may deduce its owner’s socio-economic needs or personal desire.

Ankh – Symbol of Life

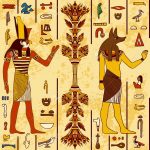

Inversely, while the selection of a particular amulet may indeed signify an aspect of an individual’s identity, the amulet itself – symbolizing a commonly held concept – also denoted a larger social system of beliefs that were intra-culturally understood. Thus, one of the ways of establishing their meaning is through the ‘reading’ of amulets within their cultural setting. For example, amulets that were carved in the form of the ☥, or ankh, were understood to impart the mystical properties of ‘everlasting life’. In an abstract sense, this may be construed from the hieroglyph ☥ which is simply translated as ‘life’.

While standalone amuletic ankhs are extremely rare, examples of the design can commonly be seen engraved on other amulets, such as the bull-bat cult specimen from Naga ed-Deir. Additionally, an ankh pendant has been found at el-Amarna, the capital of Akhenaten. Its discovery at Akhetaten – a city dedicated to the dissemination of monotheism – is a small yet intriguing example of the durability of Old to New Kingdomiconography during the turbulent Amarna Period.

The story behind this particular design is unsettled amongst scholars. For example, it is known from First Intermediate Period (2160-2055 BCE) inhumations that some amulets had anatomical associations with the human body. Hypothetically, considering the ankh’s known hieroglyphic meaning of ‘life’, one may infer a possible phallic origin for its lower cross-stem extension. In addition, the shape of the loop-handle has led some to propose a yonic interpretation. If this is true, a parallel with ancient Egyptian binary concepts regarding existence such as order/chaos, creation/destruction, and birth/death may be inferred. Furthermore, when considering the fact that the earliest ankhs have been contextually dated to the First Dynasty (3000-2890 BCE) – a time when according to Egyptian cosmology chaos and ruins were replaced by order and creation – an archaeological context that coincides with the historical ‘birth’ of ancient Egypt may be established.

Consequently, what we may be observing is a cognitive association between the Egyptian understanding of eternal life, their contemplations about creation, and their cosmological views regarding connubial relations. By extension, to the ancient Egyptians, the ankh may have been a microcosm of Egyptian history, beliefs, and interpersonal relations. Thus, a symbolic meaning – when found within an Egyptian household – could conceivably be interpreted as a desire for the magical impartation of a sound and happy marriage, prodigious fecundity, and/or a healthy and strong family. In each example, some aspect of biological or societal ‘conception’ is present (e.g. marriage, procreation). In any case, the ankh, being a unified or intersexual symbol, functions as a cultural sign for the reproductive or cyclical order of nature.

Contextually however, any definitive social interpretation would depend solely on the perception (or subjective experience) of the individual Egyptian living at the time. Thus, while we may seek to establish understandings vis-à-vis social conventions, we cannot conclusively interpret individual intention from the amulet alone, which should remind us of the importance of archaeological context. But even within context, meanings are occasionally murky. For example, it has been noted that the ankh is seldom found in non-royal burials. Deductively, one may infer a quality of ‘restriction’ or ‘aristocratic exclusivity’ regarding its use within Egyptian society. Conversely, perhaps natural or human made devastation to ‘commoner’ burials – in the form of erosion or looting – is the reason for their absence, presenting us with a much distorted picture. Nonetheless, this is only supposition and again shows us the great difficulty in establishing a precise ‘meaning’ which is here reflected in the incomplete, and ever evolving, archaeological record.