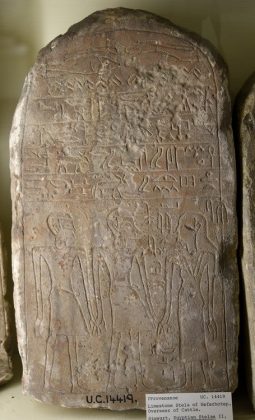

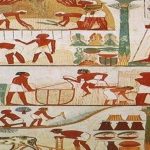

The art of the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt continued the traditions of the Middle Kingdom but often less effectively. The best artists were available to the nobility at Thebes and produced high-quality work, but non-royal artists were less skilled. This era, like the first, is also often characterized as disorganized and chaotic, and the artwork held up as proof, but there were many fine works created during this time; they were simply on a smaller scale.

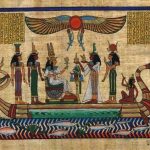

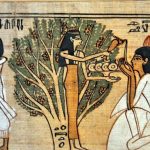

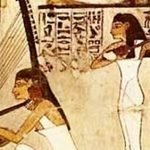

Tomb paintings, statuary, temple reliefs, pectorals, headdresses, and other jewelry of high quality continued to be produced and the Hyksos, though often vilified by later Egyptian writers, contributed to cultural development. They copied and preserved many of the written works of earlier history which are still extant and also copied statuary and other artworks.

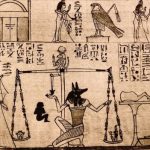

The Hyksos were finally driven out by the Theban prince Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) whose rule begins the period of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 – c. 1069 BCE). The New Kingdom is the most famous era of Egyptian history with the best-known rulers and most recognizable artwork. The colossal statues which were initiated in the Middle Kingdom became more common during this time, the temple of Karnak with its great Hypostyle Hall was expanded regularly, the Egyptian Book of the Dead was copied with accompanying illustrations for more and more people, and funerary objects like shabti dolls were of higher quality.

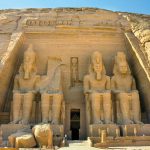

Egypt of the New Kingdom is the Egypt of empire. As the borders of the country expanded, Egyptian artists were introduced to different styles and techniques which improved their skills. The metalwork of the Hittites which the Egyptians made use of in weaponry also influenced art. The wealth of the country was reflected in the enormity of individual artworks as well as their quality. The pharaoh Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) built so many monuments and temples that later scholars attributed to him an exceptionally long reign. Among his greatest works are the Colossi of Memnon, two enormous statues of the seated king rising 60 ft (18 m) high and weighing 720 tons each. When they were built they stood at the entrance to Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple, which is now gone.

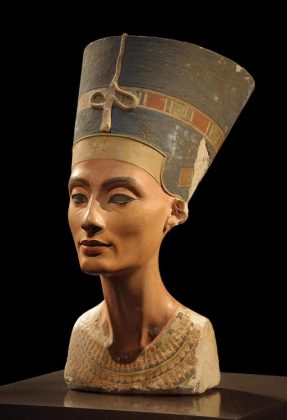

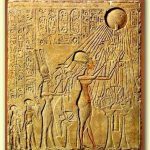

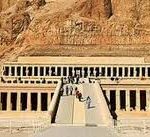

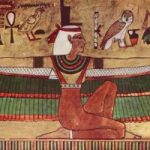

Amenhotep III’s son, Amenhotep IV, is better known as Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE), the name he chose after devoting himself to the god Aten and abolishing the ancient religious traditions of the country. During this time (known as the Amarna Period) art returned to the realism of the Middle Kingdom. From the beginning of the New Kingdom, artistic representations had again moved toward the ideal. During the reign of Queen Hatshepsut(1479-1458 BCE), although the queen is depicted realistically, most portraits of nobility show the idealism of Old Kingdom sensibilities with heart-shaped faces and smiles. The art of the Amarna period is so realistic that modern-day scholars have been able to reasonably suggest what physical ailments people in the pictures probably suffered from.

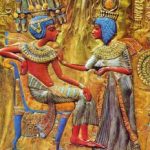

Two of the most famous works of Egyptian art come from this time: the bust of Nefertitiand the golden death mask of Tutankhamun. Nefertiti (c. 1370-1336 BCE) was Akhenaten’s wife and her bust, discovered at Amarna in 1912 CE by the German archaeologist Borchardt is almost synonymous with Egypt today. Tutankhamun (c.1336-1327 BCE) was Akhenaten’s son (but not Nefertiti’s) who was in the process of dismantling his father’s religious reforms and returning Egypt to traditional beliefs when he died before the age of 20. He is best known for his famous tomb, discovered in 1922 CE, and the vast number of artifacts it contained.

The golden mask and other metal objects found in the tomb were all the result of innovations in metalwork learned from the Hittites. The art of the Egyptian Empire is among the greatest of the civilization because of the Egyptian’s interest in learning new techniques and styles and incorporating them. Prior to the arrival of the Hyksos in Egypt, Egyptians thought of other nations as barbaric and uncivilized and did not consider them worthy of any special attention. The Hyksos ‘invasion’ forced the people of Egypt to recognize the contributions of others and make use of them.

Later Periods & Legacy

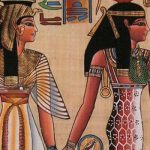

The skills acquired would continue through the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE) and Late Period (525-332 BCE), which are also negatively compared with the grander eras of a strong central government. The style of these later periods was affected by the times and the limited resources, but the art is still of considerable quality. Egyptologist David P. Silverman notes how “the art of this era reflects the opposing forces of tradition and change” (222). The Kushite rulers of the Late Period of Ancient Egypt revived Old Kingdom art in an effort to identify themselves with Egypt’s oldest traditions while native Egyptian rulers and nobility sought to advance artistic representation from the New Kingdom.

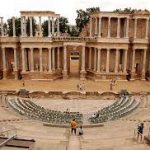

This same paradigm holds with Persian influence following their invasion of 525 BCE. The Persians also had great respect for Egyptian culture and history and identified themselves with Old Kingdom art and architecture. The Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) blended Egyptian with Greek art to create statuary like that of the god Serapis – himself a combination of Greek and Egyptian gods – and the art of the Roman Egypt (30 BCE – 646 CE) followed this same model. Romans would draw on the older Egyptian themes and techniques in adapting Egyptian gods to Roman understanding. Tomb paintings from this time are distinctly Roman but follow the precepts begun in the Old Kingdom.