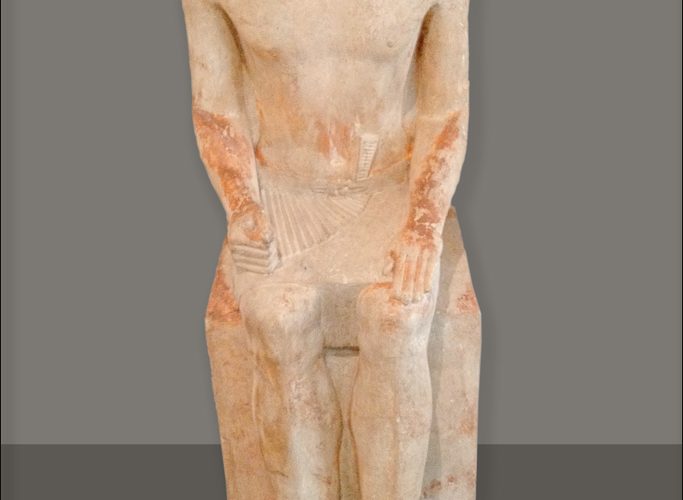

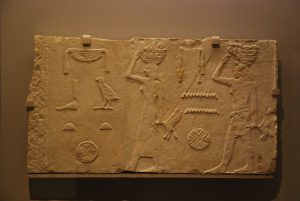

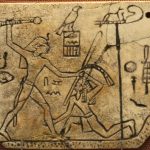

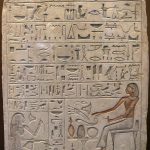

The monumental sculpture of ancient Egypt’s temples and tombs is well known,[49] but refined and delicate small works exist in much greater numbers. The Egyptians used the technique of sunk relief, which is best viewed in sunlight for the outlines and forms to be emphasized by shadows. The distinctive pose of standing statues facing forward with one foot in front of the other was helpful for the balance and strength of the piece. This singular pose was used early in the history of Egyptian art and well into the Ptolemaic period, although seated statues were common as well.

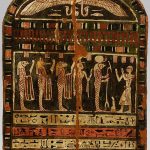

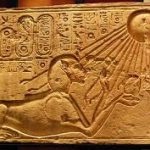

Egyptian pharaohs were always regarded as gods, but other deities are much less common in large statues, except when they represent the pharaoh as another deity; however, the other deities are frequently shown in paintings and reliefs. The famous row of four colossal statues outside the main temple at Abu Simbel each show Rameses II, a typical scheme, though here exceptionally large.[50] Most larger sculptures survived from Egyptian temples or tombs; massive statues were built to represent gods and pharaohs and their queens, usually for open areas in or outside temples. The very early colossal Great Sphinx of Giza was never repeated, but avenues lined with very large statues including sphinxes and other animals formed part of many temple complexes. The most sacred cult image of a god in a temple, usually held in the naos, was in the form of a relatively small boat or barque holding an image of the god, and apparently usually in precious metal – none of these are known to have survived.

By Dynasty IV (2680–2565 BC), the idea of the Ka statue was firmly established. These were put in tombs as a resting place for the ka portion of the soul, and so there is a good number of less conventionalized statues of well-off administrators and their wives, many in wood as Egypt is one of the few places in the world where the climate allows wood to survive over millennia, and many block statues. The so-called reserve heads, plain hairless heads, are especially naturalistic, though the extent to which there was real portraiture in ancient Egypt is still debated.

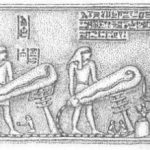

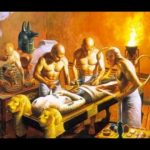

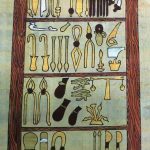

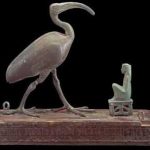

Early tombs also contained small models of the slaves, animals, buildings and objects such as boats (and later Ushabti figures) necessary for the deceased to continue his lifestyle in the afterlife.[51] However, the great majority of wooden sculpture have been lost to decay, or probably used as fuel. Small figures of deities, or their animal personifications, are very common, and found in popular materials such as pottery. There were also large numbers of small carved objects, from figures of the gods to toys and carved utensils. Alabaster was used for expensive versions of these, though painted wood was the most common material, and was normal for the small models of animals, slaves and possessions placed in tombs to provide for the afterlife.

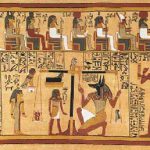

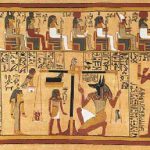

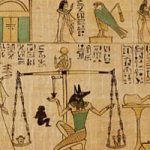

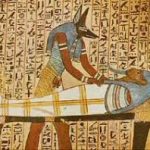

Very strict conventions were followed while crafting statues, and specific rules governed the appearance of every Egyptian god. For example, the sky god (Horus) was to be represented with a falcon’s head, the god of funeral rites (Anubis) was to be shown with a jackal’s head. Artistic works were ranked according to their compliance with these conventions, and the conventions were followed so strictly that, over three thousand years, the appearance of statues changed very little. These conventions were intended to convey the timeless and non-ageing quality of the figure’s ka.[citation needed]

A common relief in ancient Egyptian sculpture was the difference between the representation of men and women. Women were often represented in an idealistic form, young and pretty, and rarely shown in an older maturity. Men were shown in either an idealistic manner or a more realistic depiction.[27] Sculptures of men often showed men that aged, since the regeneration of ageing was a positive thing for them whereas women are shown as perpetually young.[52]