There were no religious services in Egypt corresponding to worship services in the present day. The priests served the gods, not the people, and their job was to administer to the gods’ daily needs, recite hymns and prayers for the souls of the dead, and engage in rituals which ensured the continued goodwill of the gods to the people.

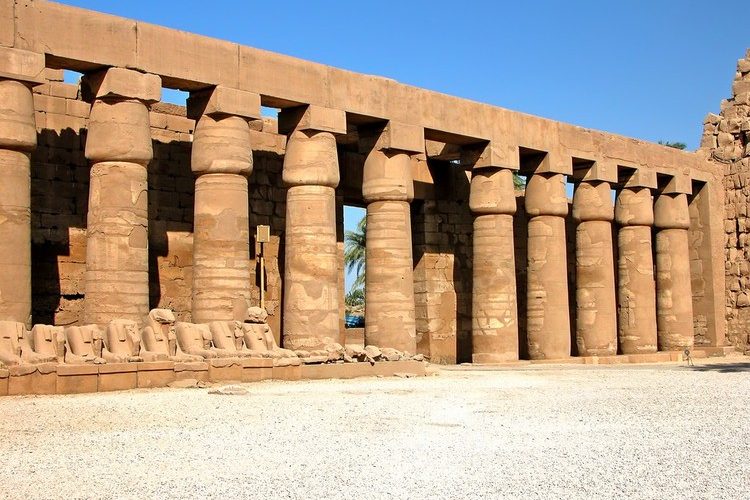

A deity was thought to live in the statue housed in the inner sanctum of that god’s temple, and the high priest was the only person allowed in its presence until the position of God’s Wife of Amun was elevated during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). At this time, the female priestess in the role of God’s Wife of Amun became the counterpart to the high priest and assisted in caring for the statue in the temple of Karnak at Thebes.

Although people would come to the temple complexes to offer sacrifices, offerings, receive various forms of aid, and make requests, they did not enter the temple to worship. Common people were allowed in the courtyard of the temple complex but not in the interiors and certainly not in the god’s presence. As noted, people performed their own private rituals in communion with the gods, but collectively, their only opportunity for worship was at a festival.

The Ancient Egyptian Festivals

The Egyptians observed national and local festivals annually. There were many such celebrations but those listed below are among the most important and best-documented. In some cases, the details of what went on at these gatherings have been lost, but for many, they are known in great detail. The festivals marked the progression of the year, notched on the staff of time by Thoth, and the year would end in the same celebration with which it had begun; thus emphasizing the cyclical, eternal, nature of life.

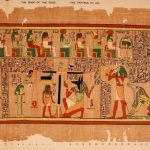

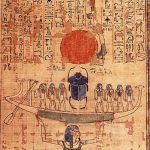

Wepet-Renpet Festival: The Opening of the Year – This was the New Year’s Day celebration in ancient Egypt. The festival was a kind of moveable feast as it depended on the inundation of the Nile River. It celebrated the death and rebirth of Osiris, and by extension, the rejuvenation and rebirth of the land and the people. It is firmly attested to as initiating in the latter part of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613 – c. 3150 BCE) and is clear evidence of the popularity of the Osiris cult at that time.

Feasting and drinking were a part of this festival, as they were for most, and the celebration would last for days; the length varied depending on the time period. Solemn rituals related to the death of Osiris were observed as well as singing and dancing to celebrate his rebirth. The call-and-response poem known as The Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys was recited at the beginning to call Osiris to his feast.

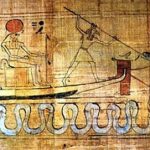

Wag Festival: Dedicated to the death of Osiris and honoring the souls of the deceased on their journey in the afterlife. This festival followed the Wepet-Renpet, but its date changed according to the lunar calendar. It is one of the oldest festivals celebrated by the Egyptians and, like Wepet-Renpet, first appears in the Old Kingdom. During this festival, people would make small boats out of paper and set them toward the west on graves to indicate Osiris’ death and people would float shrines of paper on the waters of the Nile for the same reason.

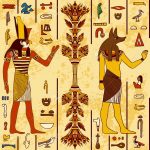

Wag and Thoth Festival: A combining of the Wag Festival with the birth of the god Thoth and centered on rejuvenation and rebirth. This festival was a set date on the 18th day of the first month of the year. Thoth was worshiped as the god of writing, wisdom, and knowledge – among other attributes – and associated with the judgment of the dead by Osiris, thus linking the two gods. Thoth’s birth and Osiris’ rebirth were joined in this festival from the latter part of the Old Kingdom onwards.

Tekh Festival: The Feast of Drunkenness: This festival was dedicated to Hathor (‘The Lady of Drunkenness’) and commemorated the time when humanity was saved from destruction by beer. According to the story, Ra had become weary of people’s endless cruelty and nonsense and so sent Sekhmet to destroy them. She took to her task with enthusiasm, tearing people apart and drinking their blood. Ra is satisfied with the destruction until the other gods point out to him that, if he wanted to teach people a lesson, he should stop the destruction before no one was left to learn from it. Ra then orders the goddess of beer, Tenenet, to dye a large quantity of the brew red and has it delivered to Dendera, right in Sekhmet’s path of destruction. She finds it and, thinking it is blood, drinks it all, falls asleep, and wakes up as the gentle and beneficent Hathor.

According to Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown, the festival began in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), was most popular in the early New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), fell out of favor, and was then revived in Roman Egypt. Graves-Brown describes the central part of the festival as depicted on a ‘Porch of Drunkenness’ in the Temple of Mut at Karnak: “It seems that in the Hall of Drunkenness, worshippers got drunk, slept, and then were woken by drummers to commune with the goddess Mut [who was closely linked with Hathor]” (169). Participants would lessen their inhibitions and preconceptions through alcohol and experience the goddess intimately upon waking to the sacred drums.

Opet Festival: One of the most important festivals in which the king was rejuvenated by the god Amun at Thebes. It was observed during the Middle Kingdom but grew in popularity in the New Kingdom of Egypt, where, in the 20th Dynasty, it was celebrated for twenty days. During this festival, the priests would first wash and dress the statue of Amun and then carry it out of the temple and through the streets of Thebes which were lined with people waiting to see the god. The statue was then transported to Luxor, by foot in earlier times, and later on a barge. Once at the temple of Luxor, the king would enter the presence of the god in the inner sanctum and emerge forgiven of sins and rejuvenated to continue his reign.

As at other festivals, the state supplied the people with food and drink, distributing bread, sweets, and beer while the crowds waited their turn to ask the god a question. The statue of Amun would answer these questions through the agency of the priests who would either interpret the god’s answer or ‘tip’ the statue one way or another to indicate a positive or negative response.

Hathor Festival: Held annually at Dendera, the main site of Hathor’s cult, this festival celebrated the birth of the goddess and her many blessings. It was similar to the Tekh Festival in many aspects. This festival dates from the Old Kingdom and was among the most anticipated. The cult of Hathor was extremely popular and, just as with the festival for Neith, the celebration was well-attended wherever it was held. As with the Tekh Festival, participants were encouraged to over-indulge in alcohol while engaging in singing and dancing in honor of the goddess. There may also have been a sexual component to the celebration similar to the Tekh Festival, but this interpretation, while not at all inconsistent or incredible, is not universally accepted.

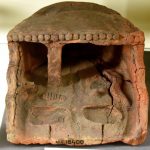

Sokar Festival/Festival of Khoiak: Sokar was an agricultural god in the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE) whose characteristics were later taken on by Osiris. In the Old Kingdom, the Sokar Festival was merged with the solemn Khoiak Festival of Osiris which observed his death. It was a very somber affair in its early form but grew to include Osiris’ resurrection as well and was celebrated in the Late Period of Ancient Egypt(525-332 BCE) for almost a month. People planted Osiris Gardens and crops during the celebrations which honored the god as the plants sprung from the earth, commemorating Osiris’ rebirth from the dead. The planting of crops during the festival no doubt dates back to the early worship of Sokar.

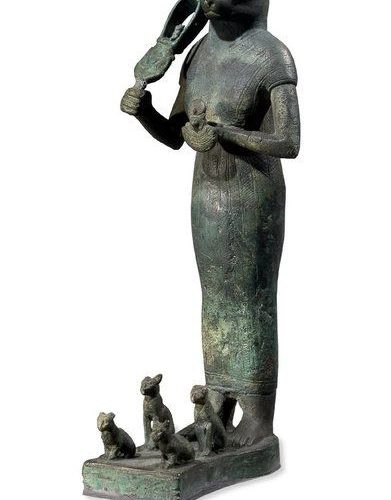

Bast Festival: This was the celebration of the goddess Bastet at her cult center of Bubastis and another very popular festival. It honored the birth of the cat goddess Bastet who was the guardian of hearth and home and protector of women, children, and women’s secrets. Herodotus claims that Bastet’s festival was the most elaborate and popular in Egypt. Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch, citing Herodotus, claims, “women were freed from all constraints during the annual festival at Bubastis. They celebrated the festival of the goddess by drinking, dancing, making music, and displaying their genitals” (116). This “raising of the skirts” by the women, described by Herodotus, exemplified the freedom from normal constraints often observed at festivals but, in this case, also had to do with fertility.

Herodotus places the number of attendees at the festival as over seven hundred thousand, and although this may be an exaggeration, there is no doubt the goddess was one of the most popular in Egypt among both sexes and so could be an accurate number. The festival revolved around dancing, singing, and drinking in honor of Bastet thanking her for gifts given and asking for future favors.

Nehebkau Festival: Nehebkau was the god who bound the ka (soul) to the khat (body) at birth and then attached the ka to the ba (the traveling aspect of the soul) after death. The festival commemorated Osiris’ resurrection and the return of his ka as the people celebrated rebirth and rejuvenation. The festival was similar in many respects to the Wepet-Renpet Festival of the New Year.

Min Festival: Min was the god of fertility, virility, and reproduction from the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 – c. 3150 BCE) onwards. He is usually represented as a man standing with an erect penis holding a flail. The Min Festival was probably celebrated in some form starting in the Early Dynastic Period but is best attested to in the New Kingdom and afterwards.

As at the Opet Festival, the statue of Min was carried out of the temple by the priests in a procession which included sacred singers and dancers. When they reached the place where the king stood, he would ceremonially cut the first sheaf of grain to symbolize his connection between the gods, the land, and the people and offer the grain to the god in sacrifice. The festival honored the king as well as the god in the hopes of a continued prosperous reign which would bring fertility to the land and the people.

Wadi Festival/The Beautiful Feast of the Valley: Similar in many ways to the Qingming Festival in China and the Day of the Dead in Mexico and elsewhere, the Beautiful Feast of the Valley honored the souls of the deceased and allowed for the living and dead to celebrate together while, at the same time, honoring Amun. The statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu (the Theban Triad) were taken from their temples to visit the mortuary temples and necropolis across the river. People visited with their departed loved ones at their tombs and brought bouquets of flowers and food and drink offerings. Egyptologist Lynn Meskell describes the focus of the celebration:

The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi was a key example of a festival of the dead, which took place between the harvest and the Nile flood. In it, the divine boat of Amun traveled from the Karnak temple to the necropolis of Western Thebes. A large procession followed and the living and dead were thought to commune near the graves which became houses of the joy of the heart on that occasion. (cited in Nardo,

Images of the deceased were carried in the procession so their souls might join in the festivities and were left in the tombs when the festival was completed. As Meskell notes, “in this way a link was forged between celebrating the gods and the dead in a single all-encompassing event” which brought the past into the present and, through the eternal gods, on into the future. The Beautiful Feast of the Valley was among the most popular in Egypt’s history and was celebrated from at least the Middle Kingdom on.

Sed Festival: Usually given as the Heb-Sed Festival, this celebration honored the king and revitalized him. It was held every thirty years of the king’s reign in order to ensure he was still in harmony with the will of the gods and physically fit to rule Egypt. The festival began with a grand procession held in front of priests, nobles, and the public. The king would need to run around an enclosed space (such as the temple complex at Saqqara) in order to prove he was fit and, in later eras, would fire arrows toward the four cardinal directions as a symbol of his power over the land and his ability to bring other nations under Egypt’s influence.

The festival probably dates from the Predynastic Period in some form but is certainly attested to from the reign of King Den (c. 2990-2940 BCE) of the First Dynasty. The name comes from the deity Sed, an early wolf-god (sometimes depicted as more of a jackal), who was originally among the most important gods, associated with the strength of the king, justice, and balance (and so linked with the goddess and concept of ma’at). Sed was eventually absorbed by Wepwawet and Anubis and superseded by Osiris who, by the New Kingdom, had taken Sed’s place in the festival. As with all the great festivals, the state provided the people with food and beer for the duration.

Although only supposed to be celebrated after the first 30 years of the king’s reign (and every three years afterwards), the Heb-Sed was sometimes observed earlier and is often referred to as the king’s jubilee. The length of a king’s reign was once dated, in part, according to the observance of the Heb-Sed until it came to be understood that some kings initiated the festival earlier than the 30-year mark if they were in poor health (and needed the gods’ rejuvenation) or for other reasons.

The Epagomenae: The Super-added Days. These were the five days at the end of the year added in order to bring the Egyptian calendar of 360 days in line with the solar year of 365. According to the myth, when Nut became pregnant by her brother Geb at the beginning of the world, it so enraged Ra (Atum) that he decreed she would not give birth on any day of the year. Thoth, however, played a game of senet with the moon god Iah (Khonsu) in which he gambled, and won, five day’s worth of moonlight. He took this moonlight and created the five “super-added days” which Nut could give birth in.

On the first day, she gave birth to Osiris, on the second Horus the Elder, on the third Set, on the fourth Isis, and on the fifth Nephthys. These days were considered a potent time of transition by the Egyptians who saw them as either auspicious or ominous depending on the deity born on a given day. The third day, when Set was born, was thought especially unlucky, and Plutarch reports that business was not transacted on the third day and people would fast until evening.

The Epagomenae were not festivals, although observances could be conducted and, no doubt, rituals were performed in temples, but still are counted among others because they formed the transition in the cycle of the year between the old and the new. Following the Epagomenae, the Wepet-Renpet Festival was again observed and a new year was begun.

Conclusion

In addition to these, there were many more festivals celebrated throughout the year, which were considered just as important by the ancient Egyptians. The Festival of Neith, for example, united the entire nation as people lighted candles and oil lamps at night to mirror the sky and bring earth into harmony with the realm of the gods. The Festival of Ptah was one of the earliest, honoring the creator god. Another, the Raising of the Djed, dates from the Predynastic Period and is another of the earliest rites observed in Egypt which came to be associated with Osiris.

There are even more besides these since, as noted, there were national and local celebrations. According to Bunson, “these ceremonies served as manifestations of the divine in human existence and, as such, wove a pattern of life for the Egyptian people” (91). Meskell notes how “religious festivals actualized belief; they were not simply social celebrations” (Nardo, 99). The festivals brought the past into the present, elevated the people toward the divine, and, on the simplest level, were times when the people could relax and enjoy themselves. The great number of such festivals in the Egyptian calendar is the clearest evidence of the value the culture placed on joy in life and the most common form of its collective expression.