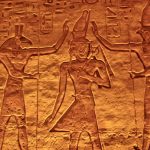

The Middle Kingdom is considered the classical age of Egyptian literature. During this time the script known as Middle Egyptian was created, considered the highest form of hieroglyphics and the one most often seen on monuments and other artifacts in museums in the present day. Egyptologist Rosalie David comments on this period:

The literature of this era reflected the added depth and maturity that the country now gained as a result of the civil wars and upheavals of the First Intermediate Period. New genres of literature were developed including the so-called Pessimistic Literature, which perhaps best exemplifies the self-analysis and doubts that the Egyptians now experienced. (209)

The Pessimistic Literature David mentions is some of the greatest work of the Middle Kingdom in that it not only expresses a depth of understanding of the complexities of life but does so in high prose. Some of the best known works of this genre (generally known as Didactic Literature because it teaches some lesson) are The Dispute Between a Man and his Ba (soul), The Eloquent Peasant, The Satire of the Trades, The Instruction of King Amenemhet I for his Son Senusret I, the Prophecies of Neferti, and the Admonitions of Ipuwer.

The Dispute Between a Man and his Ba is considered the oldest text on suicide in the world. The piece presents a conversation between a narrator and his soul on the difficulties of life and how one is supposed to live in it. In passages reminiscent of Ecclesiastes or the biblical Book of Lamentations, the soul tries to console the man by reminding him of the good things in life, the goodness of the gods, and how he should enjoy life while he can because he will be dead soon enough. Egyptologist W.K. Simpson has translated the text as The Man Who Was Weary of Life and disagrees with the interpretation that it has to do with suicide. Simpson writes:

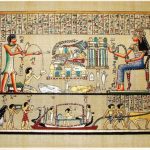

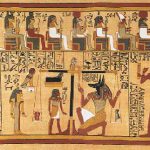

This Middle Kingdom text, preserved on Papyrus Berlin 3024, has often been interpreted as a debate between a man and his ba on the subject of suicide. I offer here the suggestion that the text is of a somewhat different nature. What is presented in this text is not a debate but a psychological picture of a man depressed by the evil of life to the point of feeling unable to arrive at any acceptance of the innate goodness of existence. His inner self is, as it were, unable to be integrated and at peace. (178)

The depth of the conversation between the man and his soul, the range of life experiences touched on, is also seen in the other works mentioned. In The Eloquent Peasant a poor man who can speak well is robbed by a wealthy landowner and presents his case to the mayor of the town. The mayor is so impressed with his speaking ability that he keeps refusing him justice so he can hear him speak further. Although in the end the peasant receives his due, the piece illustrates the injustice of having to humor and entertain those in positions of authority in order to receive what they should give freely.

The Satire of the Trades is presented as a man advising his son to become a scribe because life is hard and the best life possible is one where a man can sit around all day doing nothing but writing. All the other trades one could practice are presented as endless toil and suffering in a life which is too short and precious to waste on them.

The motif of the father advising his son on the best course in life is used in a number of other works. The Instruction of Amenemhat features the ghost of the assassinated king warning his son not to trust those close to him because people are not always what they seem to be; the best course is to keep one’s own counsel and be wary of everyone else. Amenemhat’s ghost tells the story of how he was murdered by those close to him because he made the mistake of believing the gods would reward him for a virtuous life by surrounding him with those he could trust. In Shakespeare’s HamletPolonius advises his son, “Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried/ Grapple them unto thy soul with hoops of steel/ But do not dull thy palm with entertainment of each new-hatched, unfledged courage” (I.iii.62-65). Polonius here is telling his son not to waste time on those he barely knows but to trust only those who have proven worthy. Amenemhat I’s ghost makes it clear that even this is a foolish course:

Put no trust in a brother,

Acknowledge no one as a friend,

Do not raise up for yourself intimate companions,

For nothing is to be gained from them.

When you lie down at night, let your own heart be watchful over you,

For no man has any to defend him on the day of anguish. (Simpson, 168)

The actual king Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) was the first great king of the 12th Dynasty and was, in fact, assassinated by those close to him. The Instruction bearing his name was written later by an unknown scribe, probably at the request of Senusret I (c. 1971-1926 BCE) to eulogize his father and vilify the conspirators. Amenemhat I is further praised in the work Prophecies of Neferti which foretell the coming of a king (Amenemhat I) who will be a savior to the people, solve all the country’s problems, and inaugurate a golden age. The work was written after Amenemhat I’s death but presented as though it were an actual prophecy pre-dating his reign.

This motif of the “false prophecy” – a vision recorded after the event it supposedly predicts – is another element found in Mesopotamian Naru literature where the historical “facts” are reinterpreted to suit the purposes of the writer. In the case of the Prophecies of Neferti, the focus of the piece is on how mighty a king Amenemhat I was and so the vision of his reign is placed further back in time to show how he was chosen by the gods to fulfil this destiny and save his country. The piece also follows a common motif of Middle Kingdom literature in contrasting the time of prosperity of Amenemhat I’s reign, a “golden age”, with a previous one of disunity and chaos.

The Admonitions of Ipuwer touches on this theme of a golden age more completely. Once considered historical reportage, the piece has come to be recognized as literature of the order vs. chaos didactic genre in which a present time of despair and uncertainty is contrasted with an earlier era when all was good and life was easy. The Admonitions of Ipuweris often cited by those wishing to align biblical narratives with Egyptian history as proof of the Ten Plagues from the Book of Exodus but it is no such thing.

Not only does it not – in any way – correlate to the biblical plagues but it is quite obviously a type of literary piece which many, many cultures have produced throughout history up to the present day. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that everyone, at some point in his or her life, has looked back on the past and compared it favorably to the present. The Admonitions of Ipuwer simply records that experience, though perhaps more eloquently than most, and can in no way be interpreted as an actual historical account.

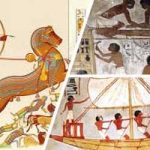

In addition to these prose pieces, the Middle Kingdom also produced the poetry known as The Lay of the Harper (also known as The Songs of the Harper), which frequently question the existence of an ideal afterlife and the mercy of the gods and, at the same time, created hymns to those gods affirming such an afterlife. The most famous prose narratives in Egyptian history – The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and The Story of Sinuhe both come from the Middle Kingdom as well. The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor holds Egypt up as the best of all possible worlds through the narrative of a man shipwrecked on an island and offered all manner of wealth and happiness; he refuses, however, because he knows that all he wants is back in Egypt. Sinuhe’s story reflects the same ideal as a man is driven into exile following the assassination of Amenemhat I and longs to return home.

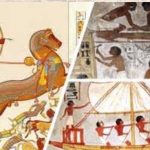

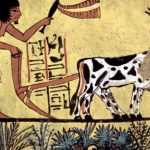

The complexities Egypt had experienced during the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) were reflected in the literature which followed in the Middle Period. Contrary to the claim still appearing in history books on Egypt, the First Intermediate Period had not been a time of chaos, darkness, and universal distress; it was simply a time when there was no strong central government. This situation resulted in a democritization of art and culture as individual regions developed their own styles which were valued as greatly as royal art had been in the Old Kingdom.

The Middle Kingdom scribes, however, looked back on the time of the First Intermediate Period and saw in it a clear departure from the glory of the Old Kingdom. Works such as The Admonitions of Ipuwer were interpreted by later Egyptologists as accurate accounts of the chaos and disorder of the era preceding the Middle Kingdom but actually, if it were not for the freedom of exploration and expression in the arts the First Intermediate Period encouraged, the later scribes could never have written the works they produced.

The royal autobiographies and Offering Lists of the Old Kingdom, only available to kings and nobles, were made use of in the First Intermediate Period by anyone who could afford to build a tomb, royal and non-royal alike. In this same way, the literature of the Middle Kingdom presented stories which could praise a king like Amenemhat I or present the thoughts and feelings of a common sailor or the nameless narrator in conflict with his soul. The literature of the Middle Kingdom opened wide the range of expression by enlarging upon the subjects one could write about and this would not have been possible without the First Intermediate Period.

Following the age of the 12th Dynasty, in which the majority of the great works were created, the weaker 13th Dynasty ruled Egypt. The Middle Kingdom declined during this dynasty in all aspects, finally to the point of allowing a foreign people to gain power in lower Egypt: The Hyksos and their period of control, just like the First Intermediate Period, would be vilified by later Egyptian scribes who would again write of a time of chaos and darkness. In reality, however, the Hyksos would provide valuable contributions to Egyptian culture even though these were ignored in the later literature of the New Kingdom.