Minoan dress had some similarities to and some marked differences from other Mediterranean civilizations. Leaping over the horns of bulls was a sport or religious ritual in which both Minoan men and women participated. Wall paintings show that for this sport, both wore loincloths reinforced at the crotch for protection. Minoan men wore skirts that ranged in length from short thigh-length versions with a tassel in the front, to longer lengths that ended below the knee or at the ankle. Skirts that appear to be very similar to the Mesopotamian kaunakes garment are also seen in Minoan art.

Women, too, wore skirts, but the construction was quite different from those of men. Scholars propose three different skirt types. All are full length. One is a bell-shaped skirt fitted over the hips and flaring to the hem. Another appears to be made of a series of horizontal ruffles widening gradually until they reach the ground, and the third is shown with a line down the center that some have interpreted as depicting a culotte-like, bifurcated skirt. Others see that line as merely showing how the skirt fell. With these skirts women often wore an apronlike overgarment. Arthur Evans, an archaeologist who was one of the earliest to study Cretan sites, suggested that the apron garment was worn for religious rituals and was a vestige of a loincloth worn by men and women in earlier times.

With these skirts, the top women wore a garment unique to the Minoans: a smoothly fitted bodice that, if the art is being accurately interpreted, had to have been cut and sewn. Tightly fitted sleeves were sewn or otherwise fastened onto the bodice. It laced or fastened underneath the breasts, leaving the bosom exposed. Authorities do not agree on whether all women bared their breasts. Some believe this style was restricted to priestesses and that ordinary women covered their breasts with a layer of sheer fabric.

With skirts or loincloths both men and women wore wide, tight belts with rolled edges. They also wore tunics. Men’s were short or long; women’s were long. Most of the tunics, as well as bodices and skirts, seem to have had woven patterned braid trimmings covering what appear to be the seam lines or points where garments would have been sewn together.

Men and women are both depicted with long or short curly hair. A variety of headwear can be seen in Minoan art, much of which may have been used in religious rituals or to designate status. Women are often shown with their hair carefully arranged and held in place with decorative nets or fillets (bands).

Greek Dress

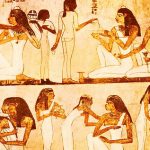

Greek sculpture and vase paintings provide numerous illustrations of Greek costume as do some wall paintings. Some even show individuals putting on or taking off clothing; therefore, scholars believe they understand what was worn and how it was constructed. Color of clothing, however, can be problematic. When first created and displayed most sculpture had been painted with colors. Those colors have been bleached away over time. For many years people believed that Greeks wore white almost exclusively. Most vase paintings are not a good source for information about color because the traditions of vase painting showed either black figures on a red background or red figures on a black background. From the few white background vases on which figures were painted in color and from frescoes it is possible to see that Greeks wore a wide range of often vivid colors.

Married women in ancient Greece ran the household. They provided for the family’s needs for textiles by spinning and weaving. Fibers used included wool, which was produced in Greece. Linen came to Greece by the sixth century B.C.E., probably making its way from Egypt to the Ionian region of Asia Minor, where some Greeks had settled, and from there to the Greek peninsula. Late in Greek history silk evidently came from China by way of Persia, and the Greek island of Cos was known for its silk production. Imported woven silk fabrics were probably unraveled into yarns and then combined with linen yarns and woven into fabrics. In this way, less of the precious silk was needed to make a highly decorative fabric.

Dyes were made from plants and minerals. A particularly prized and valuable color was purple, which was obtained from shellfish. Dyeing, bleaching, and some other finishing processes were probably carried out in special facilities, not in the home, because of the noxious fumes they produced. Women were skilled in decorating fabric with embroidery and woven designs. Garments were draped and were most likely woven to the correct size and therefore required little cutting and sewing. Many garments appear to be pleated, so it is likely that there were devices for pressing pleats into fabric and for keeping textiles smooth and flat.

Major Costume Forms

The Greek name for the garment roughly equivalent to a tunic was chiton, which is what costume historians now call Greek tunics. Throughout Greek history one form or another of the chiton was the basic garment for men, women, and children. Its size, shape, and methods of fastening varied over time. Even so, the chiton was constructed in much the same way throughout Greek history. A rectangular length of fabric was folded in half lengthwise and placed around the body under the arms with the fold on one side and the open edge on the other. The top of the fabric was pulled up over the shoulder in the front to meet the fabric in the back, and pinned. This was repeated over the other shoulder. This rudimentary garment was belted at the waist. Sometimes the open side was sewn or it may have been pinned or left open. By beginning with this simple garment, variations could be made easily. Often the top edge of the fabric was folded down to form a decorative overfold. The width of the folded section could vary. Belts could be placed at various locations or multiple belts could be used. The method of pinning the shoulder could also change.

The names used today for these different styles are not necessarily those given to them by the ancient Greeks, but have been assigned later by costume historians who sometimes differ about terminology. The terms employed here are those that appear to be most commonly accepted.

In the Archaic Period, the chiton type garments are known as the chitoniskos and the Doric peplos. Both had the same construction and were made with an overfold that came to about waist length. They appear to have been closely fitted and seem to have been made from patterned wool fabrics. Men wore the chitoniskos, which was usually short and ended between the hip and the thigh. Women wore the Doric peplos, similar in shape and fit but reaching to the floor. The Doric peplos was fastened with a long, sharp, daggerlike decorative pin.

Herodotus says that the transition from the Doric peplos to the Ionic chiton came about because the women of Athens were said to have used their dress pins to stab to death a messenger who brought them the news of the resounding defeat of the Athenians in a battle. Herodotus says that the use of these large pins was outlawed, and small fastenings mandated instead.

This story may be apocryphal, but it is true that the Ionic chiton did replace the Doric peplos for both men and women soon after 550 B.C.E. The Ionic chiton was made from a wider fabric and was pinned with many small fasteners part or all of the way down the length of the arm. With more fabric in the garment, overfolds were less likely to be used. Instead other shawls or small rectangular garments were placed over the chiton. Many of the wider Ionic chitons appear to be pleated and were most likely made of lighter weight wool or of linen. Styles could be varied by belting the fabric in different ways.

Around 400 B.C.E. the Ionic chiton gradually gave way to the Doric chiton. The Doric chiton was narrower and fastened at the shoulder with a single pin very much like a decorative safety pin. The Romans called such pins fibulae and this Latin term is now used for any such pin from ancient times. This garment was more likely than the Ionic chiton to have an overfold. Doric chitons could also be worn with the previously mentioned small draped garments and belted in various ways. They seem to have been made from wool, linen, or silk.

Some scholars see the transition from the large, ostentatious Ionic chiton to the simpler Doric chiton as reflecting changes in attitudes and values in Greek society. A. G. Geddes (1987) suggests that in the late fifth century B.C.E. emphasis was being placed on physical fitness (more obvious in the more fitted Doric chiton), equality, and less flaunting of wealth.

The Hellenistic chiton appears from around 300 to 100 B.C.E. It was a refinement of the Doric chiton that was narrower, belted just beneath the breasts, and made of lighter weight wool cloth, linen, or silk. It is this chiton that is closest in style to many of the later garment styles that were inspired by the Greek chiton.

In general, styles for men and women were very similar, with women’s garments reaching to the floor and men’s more likely to be short for daily use. A poor man’s version of the chiton was the exomis, a simple rectangle of cloth that fastened over one shoulder, leaving the other arm free for easier action.

Several garments seem to have been used more by men than women. The himation was a large rectangle of fabric that wrapped around the body. In use from the late fifth century, the garment might be worn alone or over a chiton. It covered the left shoulder, wrapped across the back and under the right arm, then was thrown over the left shoulder or carried across the left arm. For protection against inclement weather and while traveling, men wore a rectangular cloak of leather or wool called the chlamys. It could also be used as a blanket. The petasos, a wide-brimmed hat that offered additional protection against sun or rain was often worn with this cloak.

The question of whether married, adult Greek women were required to be veiled when out-of-doors is still debated. Some statues do seem to show this. A respectable married woman’s activities were limited; most of her time was spent in the home and she was excluded from men’s social gatherings. The women shown socializing with men in Greek art are courtesans or entertainers, not wives. Some scholars believe that when a woman went outside the home, she pulled a mantle or veil over her head to obscure her face. C. Galt (1931) suggests that veiling came to Greece from Ionia in the Middle East about the time the Ionian chiton was adopted.