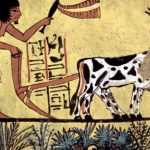

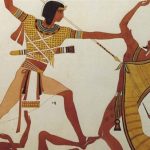

The Egyptians maintained a largely vegetarian diet. Meat was expensive, could not last long as there was no concept of refrigeration, and so was primarily reserved for nobility, the wealthy, and for festivals and special occasions. Animals used for meat included cattle, lambs, sheep, goats, poultry, and for the nobles, antelope killed in the hunt. Pigs were regularly eaten in Lower Egypt while shunned (along with anyone associated with them) in Upper Egypt during certain periods. Fish was the most common food of the lower classes but considered unclean by many upper-class Egyptians; priests, for example, were forbidden to eat fish.

The staple crops of ancient Egypt were emmer (a wheat-grain), chickpeas and lentils, lettuce, onions, garlic, sesame, corn, barley, papyrus, flax, the castor oil plant, and – during the period of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) at Thebes – the opium poppy.

Opium was used for medicinal purposes and recreation from as early as c. 3400 BCE in Sumeria, where the Mesopotamians referred to it as Hul Gil (‘the joy plant’), and cultivation of the poppy passed on to other cultures such as the Assyrian and Egyptian. By the time of the New Kingdom, the opium trade was quite lucrative and contributed to the great wealth of the city of Thebes.

Papyrus was used for a number of products. Although it is most commonly recognized as the raw material for paper, papyrus was also used to make sandals, rope, material for dolls, boxes, baskets, mats, window shades, as a food source, and even to make small fishing boats. The castor oil plant was crushed and used for lamp oil and also as a tonic. Flax was used for rope and clothing and sometimes in the manufacture of footwear.

Among the most important crops was the emmer which went into the production of beer, the most popular drink in Egypt, and bread, a daily staple of the Egyptian diet. When Rome annexed Egypt after 30 BCE, wheat production gradually declined in favor of the cultivation of grapes because the Romans favored wine over beer. Prior to the coming of Rome, however, emmer was probably the most important crop regularly grown in Egypt after papyrus.

Farmers & Trade

The individual farmers would make their living from the crops in a number of ways. If one were a private landowner, of course, one could do as one wished with one’s crops (keeping in mind that one would have to pay a certain amount to the state in taxes). Most farmers worked on land owned by the nobles or the priests or other wealthy members of society, and so the men would typically tend the fields and surrender the produce to the noble while keeping a small amount for personal use. The wives and children of these tenant farmers often kept small gardens they tended for the family, but agriculture was primarily a man’s work. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley writes:

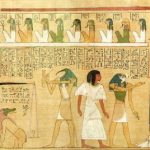

Women are not conventionally illustrated ploughing, sowing, or looking after the animals in the fileds, but they are shown providing refreshments for the labourers, while gleaning was an approved female outdoor activity recorded in several tombscenes; women and children follow the official harvesters and pick up any ears of corn which have been left behind. Of equal, or perhaps greater, importance were the small-scale informal transactions conducted between women, with one wife, for example, simply agreeing to swap a jug of her homemade beer for her neighbour’s excess fish. This type of exchange, which formed the basis of the Egyptian economy, allowed the careful housewife to convert her surplus directly into useable goods, just as her husband was able to exchange his labour for his daily bread.

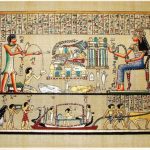

Such exchanges, in good years, often involved the family garden and produce served as currency in transactions. Fishing was a daily activity for many, if not most, of the lower classes as a means to supplement their income, and Egyptians were known as expert fishermen. Ancient Egypt was a cashless society up until the time of the Persian Invasion of 525 BCE, and so the more one had to barter with, the better one’s situation.

Agriculture & Personal Wealth

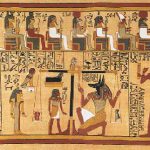

The monetary unit of ancient Egypt was the deben which, according to historian James C. Thompson, “functioned much as the dollar does in North America today to let customers know the price of things, except that there was no deben coin” (Egyptian Economy, 1). A deben was “approximately 90 grams of copper; very expensive items could also be priced in debens of silver or gold with proportionate changes in value” (ibid). Thompson continues:

Since seventy-five litters of wheat cost one deben and a pair of sandals also cost one deben, it made perfect sense to the Egyptians that a pair of sandals could be purchased with a bag of wheat as easily as with a chunk of copper. Even if the sandal maker had more than enough wheat, she would happily accept it in payment because it could easily be exchanged for something else. The most common items used to make purchases were wheat, barley, and cooking or lamp oil, but in theory almost anything would do.

This same system of barter which took place on the most modest scale throughout the villages of Egypt was also the paradigm in the cities and in international trade. Egypt shipped its produce to Mesopotamia, the Levant, India, Nubia, and the Land of Punt(modern-day Somalia) among others. Crops were harvested and stored at the local level and then a portion collected by the state and moved to the Royal Granaries in the capital as taxes.

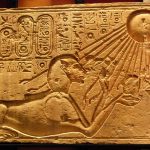

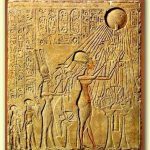

Bunson notes how “assessors were sent from the capital to the provinces to collect taxes in the form of grain” and how the local temples “had storage units and were subject to taxes in most eras unless exempted for a particular reason or favor” (5). Temples to especially popular gods, such as Amun, grew wealthy from agriculture, and Egypt’s history repeatedly turns on conflicts between the priests of Amun and the throne.