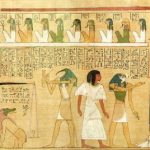

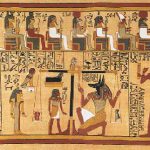

The concept of the afterlife changed in different eras of Egypt’s very long history, but for the most part, it was imagined as a paradise where one lived eternally. To the Egyptians, their country was the most perfect place which had been created by the gods for human happiness. The afterlife, therefore, was a mirror image of the life one had lived on earth – down to the last detail – with the only difference being an absence of all those aspects of existence one found unpleasant or sorrowful. One inscription about the afterlife talks about the soul being able to eternally walk beside its favorite stream and sit under its favorite sycamore tree, others show husbands and wives meeting again in paradise and doing all the things they did on earth such as plowing the fields, harvesting the grain, eating and drinking.

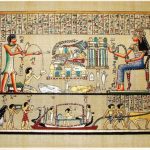

In order to enjoy this paradise, however, one would need the same items one had during one’s life. Tombs and even simple graves included personal belongings as well as food and drink for the soul in the afterlife. These items are known as ‘grave goods’ and have become an important resource for modern-day archaeologists in identifying the owners of tombs, dating them, and understanding Egyptian history. Although some people object to this practice as ‘grave robbing,’ the archaeologists who professionally excavate tombs are assuring the deceased of their primary objective: to live forever and have their name remembered eternally. According to the ancient Egyptians’ own beliefs, the grave goods placed in the tomb would have performed their function many centuries ago.

Food, Drink & Shabti Dolls

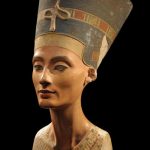

Grave goods, in greater or lesser number and varying worth, have been found in almost every Egyptian grave or tomb which was not looted in antiquity. The articles one would find in a wealthy person’s tomb would be similar to those considered valuable today: ornately crafted objects of gold and silver, board games of fine wood and precious stone, carefully wrought beds, chests, chairs, statuary, and clothing. The finest example of a pharaoh’s tomb, of course, is King Tutankhamun’s from the 14th century BCE discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 CE, but there have been many tombs excavated throughout ancient Egypt which make clear the social status of the individual buried there. Even those of modest means included some grave goods with the deceased.

The primary purpose of grave goods, though, was not so show off the deceased person’s status but to provide the dead with what they would need in the afterlife. A wealthy person’s tomb, therefore, would have more grave goods – of whatever that person favored in life – than a poorer person. Favorite foods were left in the tomb such as bread and cake, but food and drink offerings were expected to be made by one’s survivors daily. In the tombs of the upper-class nobles and royalty an offerings chapel was included which featured the offerings table. One’s family would bring food and drink to the chapel and leave it on the table. The soul of the deceased would supernaturally absorb the nutrients from the offerings and then return to the afterlife. This ensured one’s continual remembrance by the living and so one’s immortality in the next life.

If a family was too busy to tend to the daily offerings and could afford it, a priest (known as the ka-priest or water-pourer) would be hired to perform the rituals. However the offerings were made, though, they had to be taken care of on a daily basis. The famous story of Khonsemhab and the Ghost (dated to the New Kingdom of Egypt c. 1570-1069 BCE) deals with this precise situation. In the story, the ghost of Nebusemekh returns to complain to Khonsemhab, high priest of Amun, that his tomb has fallen into disrepair and he has been forgotten so that offerings are no longer brought. Khonsemhab finds and repairs the tomb and also promises that he will make sure offerings are provided from then on. The end of the manuscript is lost, but it is presumed the story ends happily for the ghost of Nebusemekh. If a family should forget their duties to the soul of the deceased, then they, like Khonsemhab, could expect to be haunted until this wrong was righted and regular food and drink offerings reinstated.

Beer was the drink commonly provided with grave goods. In Egypt, beer was the most popular beverage – considered the drink of the gods and one of their greatest gifts – and was a staple of the Egyptian diet. A wealthy person (such as Tutankhamun) was buried with jugs of freshly brewed beer whereas a poorer person would not be able to afford that kind of luxury. People were often paid in beer so to bury a jug of it with a loved one would be comparable to someone today burying their paycheck. Beer was sometimes brewed specifically for a funeral, since it would be ready, from inception to finish, by the time the corpse had gone through the mummification process. After the funeral, once the tomb had been closed, the mourners would have a banquet in honor of the dead person’s passing from time to eternity, and the same brew which had been made for the deceased would be enjoyed by the guests; thus providing communion between the living and the dead.

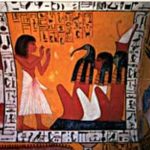

Among the most important grave goods was the shabti doll. Shabti were made of wood, stone, or faience and often were sculpted in the likeness of the deceased. In life, people were often called upon to perform tasks for the king, such as supervising or laboring on great monuments, and could only avoid this duty if they found someone willing to take their place. Even so, one could not expect to shirk one’s duties year after year, and so a person would need a good excuse as well as a replacement worker.

Since the afterlife was simply a continuation of the present one, people expected to be called on to do work for Osiris in the afterlife just as they had labored for the king. The shabti doll could be animated, once one had passed into the Field of Reeds, to assume one’s responsibilities. The soul of the deceased could continue to enjoy a good book or go fishing while the shabti took care of whatever work needed to be done. Just as one could not avoid one’s obligations on earth, though, the shabti could not be used perpetually. A shabti doll was good for only one use per year. People would commission as many shabti as they could afford in order to provide them with more leisure in the afterlife.

Shabti dolls are included in graves throughout the length of Egypt’s history. In the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) they were mass-produced, as many items were, and more are included in tombs and graves of every social class from then on. The poorest people, of course, could not even afford a generic shabti doll, but anyone who could, would pay to have as many as possible. A collection of shabtis, one for each day of the year, would be placed in the tomb in a special shabti box which was usually painted and sometimes ornamented.