The civilization of Ancient Egypt came into being in North Africa in the lands along the Nile River when two kingdoms united during a so-called Early Dynastic Period (c. 3200-2620 B.C.E.). Historians divide the history of Egypt into three major periods: Old Kingdom (c. 2620-2260 B.C.E.), the Middle Kingdom (c. 2134-1786 B.C.E.), and the New Kingdom (c.1575-1087 B.C.E.). Throughout this entire period Egyptian dress changed very little.

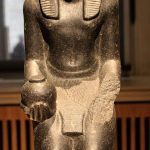

The structure of Egyptian society also seems to have changed little throughout its history. The pharaoh, a hereditary king, ruled the country. The next level of society, deputies and priests, served the king, and an official class administered the royal court and governed other areas of the country. A host of lower level officials, scribes, and artisans provided needed services, along with servants and laborers, and, at the bottom, were slaves who were foreign captives.

The hot and dry climate of Egypt made elaborate clothing unnecessary. However, due to the hierarchical structure of society, clothing served an important function in the display of status. Furthermore, religious beliefs led to some uses of clothing to provide mystical protection.

Sources of Evidence About Dress

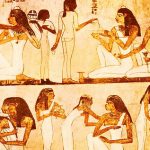

It is religious beliefs that have provided much of the evidence for dress of this period. Egyptians believed that by placing real objects, models of real objects, and paintings of daily activities in the tomb with the dead, the deceased would be provided with the necessities for a comfortable afterlife. Depictions and actual items of clothing and accessories were among the materials included. The hot, dry climate preserved these objects. Works of art from temples and surviving inscriptions and documents are additional sources of information.

Textile Availability and Production

Linen fiber, obtained from the stems of flax plants, was the primary textile used in Egypt. Wool was not worn by priests or for religious rituals and was considered “unclean” although the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 490 B.C.E.) reported that he saw wool fabrics in use. From samples of fabric that have been preserved, it is evident that the Egyptians were highly skilled in linen production. They made elaborately pleated fabrics, probably by pressing dampened fabrics on grooved boards. Tapestry woven fabrics appeared after 1500 B.C.E. Beaded fabrics are found in tombs, as are embroidered and appliquéd fabrics.

Major Costume Forms

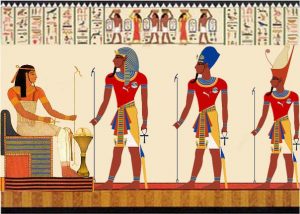

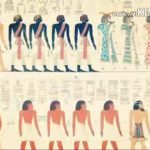

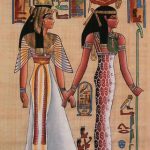

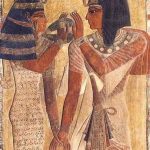

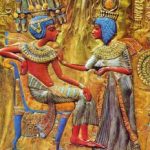

Draped or wrapped clothing predominated in Egyptian dress. Lower status men wore the simplest of garments: a loincloth of linen or leather, or a leather network covering a loincloth. Men of all classes wore wrapped skirts, sometimes called schenti, shent, skent, or schent by costume historians. The precise shape of these skirts varied depending on whether the fabric was pleated or plain (more often plain in the Old Kingdom, more likely pleated in the New Kingdom), longer or shorter (growing longer for high status men in the Middle Kingdom and after), fuller (in the New Kingdom) or less full (in the Old Kingdom). Royalty and upper-class men often wore elaborate jeweled belts, decorative panels, or aprons over skirts.

Coverings for the upper body consisted of leopard or lion skins, short fabric capes, corselets that were either strapless or suspended from straps, and wide, decorative necklaces. Over time the use of animal skins diminished. These became symbols of power, worn only by kings and priests. Eventually cloth replicas with painted leopard spots replaced the actual skins and seemed to have had a purely ritual use.

Tunics appear in Egyptian dress during the New Kingdom, possibly as a result of cross-cultural contact with other parts of the region or the conquest and political dominance of Egypt for a time by foreigners called the Hyksos.

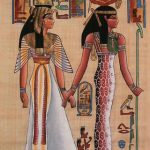

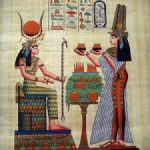

Long wrapped garments appear to have been worn by both men and women until the Middle Kingdom, after which they appear only on women, gods, and kings. Instead during the New Kingdom men were shown wearing long, loose, flowing pleated garments, the construction of which is not entirely clear. Shawls were worn as an outermost covering and were either wrapped or tied.

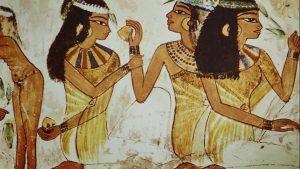

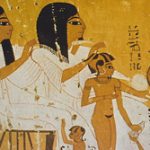

Slaves and dancing girls were sometimes shown as being naked or wearing only a pubic band. Laboring women wore skirts when at work. Women, especially those of lower socioeconomic status, wore long, loose tunics, similar to those worn by men. From the writings of Herodotus, it appears this garment was called a kalasiris. Some costume historians have mistakenly used this term to refer to a tightly fitted garment that appears on women of all classes. Although this garment has the appearance of a tightly fitted sheath dress, it is thought that this representation is probably an artistic convention, not a realistic view. The garment was more likely to have been a length of fabric wrapped around the body. Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood (1993) in an extensive study of garments from Egyptian tombs has found no examples of sheath dresses, but has found lengths of cloth with patterns of wear that are consistent with such wrapped garments.

Sheathlike garments are often shown with elaborate patterns. Suggestions for how the patterns were made have included weaving, painting, appliqué, leatherwork, and feathers. The more likely answer is that beaded net dresses, found in a number of tombs, were placed over a wrapped dress.

Garments from tombs from the Old Kingdom and after also include simple V-necked linen dresses made without sleeves. A later, sleeved version has a more complex construction that required sewing a tubular skirt to a yoke.

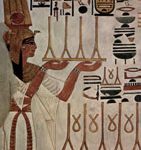

Like men, high status women wore long, full, pleated gowns in the New Kingdom. Careful examination of representations of these gowns indicates that the method of draping these garments that was used by women was different from those of men. Like men, women used wrapped shawls to provide warmth or cover.

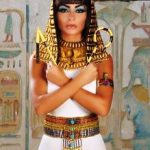

Egyptian jewelry often provided the main sources of color in costume. Wide jeweled collars, jeweled belts and aprons, amulets worn around the neck to ward off evil, diadems with real or jeweled flowers, armlets, bracelets, and, during the New Kingdom, earrings were all part of the repertoire of ornaments available to men and women.

Headdress and hair coverings were often used to communicate status. As a result works of art show a wide variety of symbolic styles. The pharaoh wore a crown, the pschent, that was made by combining the traditional crown of Lower Egypt with the traditional crown of Upper Egypt. This crown was a visible symbol of the king’s authority over both Upper and Lower Egypt. Other symbolic crowns and headdresses also are seen: the hemhemet crown, worn on ceremonial occasions; the blue or war crown when going to war; the uraeus, a representation of a cobra worn by kings and queens as a symbol of royal power. The nemes headdress, a scarflike garment fitted across the forehead, hanging down to the shoulder behind the ears, and having a long tail (symbolic of a lion’s tail) in back was worn by rulers. Queens or goddesses wore the falcon headdress, shaped like a bird with the wings hanging down at the side of the face.

Men, and sometimes women and children, shaved their heads. Although men were clean-shaven, beards were symbols of power and the pharaoh wore a false beard. When artists depict Hatshepsut, a female pharaoh, she, too, is shown with this false beard. The children of the pharaoh had a distinctive hairstyle, the lock of Horus or the lock of youth. The head was shaved, and one lock of hair was allowed to grow on the left side of the head where it was braided and hung over the ear.