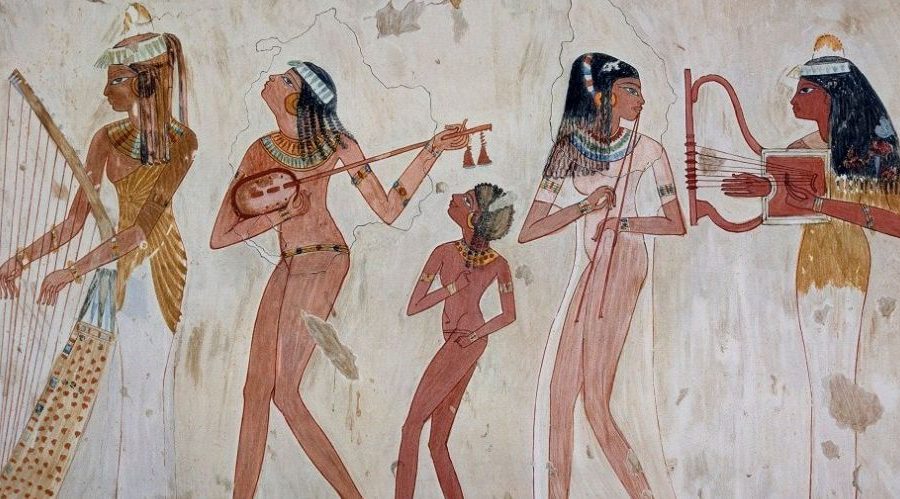

By the time of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 – c. 1069 BCE) music was well established as a part of Egyptian life. The famous poetic genre of the love song, so closely associated with the New Kingdom, may have developed to be sung and accompanied by interpretative dance. Whether the love song developed as a song lyric is uncertain but interpretative dance was a regular part of religious rituals. Egyptologist Gay Robins describes an engraving from the reign of Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) depicting a musical performance. A male harpist performs and sings a hymn to the deity while women appear to dance interpretatively:

A number of acrobatic dancers are shown doing back-bends, or dancing energetically with their hair falling over their faces. In one scene, their actions are captioned ‘dancing by the dancers’. Other women are not dancing but shake their sistra with one hand and hold a menit necklace in the other; they also sing a hymn. (146)

Music and dance served to elevate participants in religious ceremonies toward a closer relationship with the deity. Hymns to the gods were sung to the accompaniment of musical instruments and dance, and there was no proscription on who could or could not dance at any given time. Although the upper class do not seem to have danced publicly as the lower class did, there are clear instances in which the king danced.

Perhaps part of the reason upper-class men and women are not shown dancing is because of the close association it had with public entertainment in which dancers wore next to nothing. The problem would not have been with nudity but with associating one’s self with the lower class. Ancient Egyptians, in any era of the culture, were completely comfortable with their naked bodies and those of others. Scholar Marie Parsons comments on this:

Women who danced (and even women who did not) wore diaphanous robes, or simply belt girdles, often made of beads or cowrie shells, so that their bodies could move about freely. Though today their appearance may be interpreted as erotic and even sensual, the ancient Egyptians did not view the naked body or its parts with the same fascination that we do today, with our sense of possibly more repressed morality. (2)

Whether in the temple or in public performances, the gods were invoked through dance. The gods and goddesses of Egypt were present everywhere, in every aspect of one’s life, and were not restricted simply to temple worship. A practice of ‘impersonating’ a deity grew up in which the dancer would take on the attributes of the divine and interpret the higher realms for an audience. The most popular deity associated with this is Hathor.

Dancers would imitate the goddess by invoking her epithet, The Golden One, and enacting stories from her life or interpreting her spirit through dance. Dancers would often have tattoos representing the protective aspect of Hathor or the god Bes, and priestesses were known as Hathors and, in some periods, wore horned headdresses to associate themselves with Hathor’s aspect as a cow-goddess.

Types of Dance

Marie Parsons cites the types of dances most common in Egyptian practice:

1. The purely movemental dance. A dance which was little more than an outburst of energy, where the dancer and audience alike simply enjoyed the movement and its rhythm.

2. The gymnastic dance. Some dancers excelled at more strenuous and difficult movements, which required training and great physical dexterity and flexibility. These dancers also refined their movements so as to move delicately.

3. The imitative dance. These appeared to be emulative of the movements of animals, only obliquely referred to in Egyptian texts while not actually being represented in art.

4. The pair dance. Pairs in ancient Egypt were formed by two men or by two women dancing together, not by men dancing with women. The movements of these dancers were executed in perfect symmetry, indicating, at least to the author of this treatise, that the Egyptians were deeply conscious and serious about this dance as something more than just movement.

5. The group dance. These fell into two sub-types, one taking place with perhaps at least four, sometimes as many as eight, dancers, each performing different movements, independent of each other, but in matching rhythms. The other sub-type was the ritual funeral dance, performed by ranks of dancers executing identical movements.

6. The war dance. These were apparently recreations for resting mercenary troops of Libyans, Sherdans, Pedtiu (peoples who formed parts of the so-called Sea Peoples) and other groups.

7. The dramatic dance. From the examples used herein, the author is considering a depicted familiar posture of several girls as being performed to commemorate a historical tableau: a kneeling girl represents a defeated enemy king, a standing girl the Egyptian king, holding the enemy with one hand by the hair and with the other a club.

8. The lyrical dance. The description of this dance indicates it told its own story, much as a ballet we may see today. A man and a girl dancer using wooden clappers which gave their steps rhythm danced in harmonious movement, separately or together, sometimes pirouetting, parting, and approaching, the girl fleeing from the man, who tenderly pursued her.

9. The grotesque dance. These were apparently primarily performed by dwarves such as the one Harkhuf was asked to bring back to dance “the divine dances”.

10. The funeral dance. These formed three sub-types. One was the ritual dance, forming part of the actual funeral rite. Then there were the expressions of grief, where the performers placed their hands on their heads or made the ka gesture, both arms upraised. The third sub-type was a dance to entertain the ka of the deceased.

11. The religious dance. Temple rituals included musicians trained for the liturgy and singers trained in the hymns and other chants.

All of these dances, for whatever purpose, were thought to elevate the spirit of the dancer and of the audience of spectators or participants. Music and dance called upon the highest impulses of the human condition while also consoling people on the disappointments and losses in a life. Dance and music at once elevated and informed not only one’s present circumstance but the universal meaning of triumph and suffering.

Conclusion

The association of music and dance with the divine was recognized by ancient cultures around the world, not only in Egypt, and both were incorporated into spiritual rituals and religious ceremonies for thousands of years. The present-day aversion to dance and so-called ‘secular music’ stems from the condemnation of both with the rise of Christianity.

Although some church fathers such as Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE) saw evidence in the scriptures encouraging dance (such as King David’s famous spontaneous dancing for God in II Samuel 6:14-16), most saw dance as a continuation of heathen practices and forbade it. By the time of the Byzantine Empire (330 CE), dancing had been proscribed as immoral and music was separated into the categories of liturgical and secular.

The Byzantine Empire still approved, somewhat tentatively, of both but the church of Rome did not. It is for this reason that the Eastern Orthodox Church still encourages dance and music in religious services while the Catholic Church, until very recently, has not. Long before either of these sects of the new religion blossomed, the ancient Egyptians recognized the power of music and dance to elevate the soul and open new perspectives and, for over three thousand years, people were encouraged and inspired by music, the force which helped give birth to and shape the universe, and dance, which is the human response to creation.