by Salah Zaimeche

Nothing contrasts more the discrepancies in learning as the place of books. When Muslim libraries abounded with books, some containing even tens of thousands, and where students, scholars and any curious mind found a place, there was hardly anything of worth in any part of the Christian West, not just the British Isles. Even by the early so-called Renaissance (around the late 15th century) few books existed in Christian Europe excepting those preserved in monasteries……

Von Grunebaum remarks:

Modern Muslim society as a whole is lamentably ignorant of the origin, development, and achievements of its civilisation. This ignorance is due partly to a defective educational system.”[1]

Which raises two interesting issues:

First, the obvious, Muslim society, as a whole, has little, if any, idea at all of the impact its civilisation has exerted on the modern world and modern science and civilisation. Hardly will it occur to most Muslims that the English speaking world, which dominates our modern civilisation, had at some point acquired its learning and science from the Muslims. Which is a lamentable state, indeed.

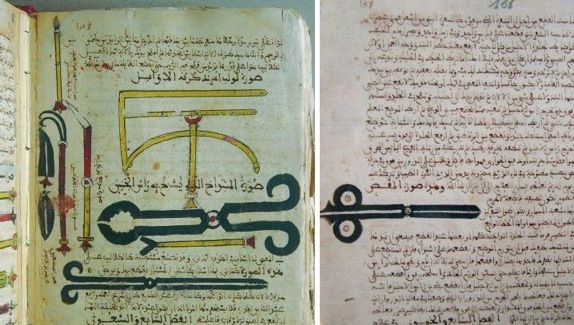

Figure 1. Manuscript from the medical treatise of Al-Zahrawi in the General Library in Rabat, Morocco (Source)

Secondly, equally obvious, if the Muslims themselves ignore their contribution, why should others acknowledge it for them. Hence the general great silence from the English speaking world, just as from others, about the Islamic contribution to their scientific revival. In fact, one is wrong to refer to the great silence of the non Muslim world in respect to the impact of Muslim civilisation. Indeed, had it not been for non Muslim scholars and historians, Muslims today would know near to nothing about anything, including their own history and the impact of their civilisation on the modern world.

Whilst these words are harsh, they express a lamentable reality and weakness on the part of Muslim scholarship and other elites and institutions meant to inform or teach, an issue on which this author has no wish to dwell, and also this not being the right venue. One, however, must note the few exceptions such as such great figures of Muslim scholarship in the field: Sezgin, Rashed, Djebbar, Al Hassan, Ihsanoglu, and a few others who achieved a considerable amount in the field, and also some Muslim institutions such as Al Furqan of London, IRCICA of Istanbul, and the web-site muslimheritage. What should be stressed, indeed, is that, if it weren’t for scholars of the calibre of Sarton, Haskins, and many other so called Orientalists (Gibb, Amari, Guillaume, Arnold, Carra de Vaux…) our knowledge of both Islamic history and civilisation would be near nil. If it weren’t for many scholars of today, also, especially those from the Anglo-Saxon world, America and England, primarily, the likes of David King, Donald Hill, Thomas Glick, Andrew Watson (from Canada), Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom, Fairchild Ruggles, D.C. Lindberg, Harley and Woodward, and few others to be named gradually as this essay progresses, poor, indeed, would be our grasp of the vast Islamic contribution to the rise of modern sciences and civilisation.[2] Whilst we are on this Western scholarly contribution, and in relation to our specific subject, i.e the impact of Muslim learning on England, if it weren’t for someone like Charles Burnett, as an instance, our knowledge of such an impact would be utterly incomplete and flawed.[3] Besides Burnett, other scholars, such as Melitzki, Cochrane, Harvey, Sweetman, and a few more, have enlightened us on the vast impact Islamic civilisation and sciences had on the British Isles, and England, most particularly.[4] Some books such as Briffault’s Troubadours, and G.A. Russell’s edition of The Arabick Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth Century England, are absolute gems which are necessary for anyone to understand some issues of fundamental importance as far as such an impact went.[5]

Relying on such a Western scholarship, the following essay will outline how Islamic civilisation impacted on the rise of science and learning, and the arts and architecture of England.[6] It will also show other aspects of impact, including the arts of gardening, and how England owes a great deal of its richness in the field thanks to the imports of many plants and flowers from the Muslim world, Turkey, most particularly.[7]

Before this is done, first and foremost, journey must be made to the days when such a transfer began, and explain the conditions of both civilisations, Muslim and British/English, and the sharp contrasts between the two, so as to appreciate fully the scope of the Muslim impact.

Contrasts Between Islamic and English/British Isles Societies:

The glimmering lamp of knowledge was sustained when it was all but ready to die out. By the Arabians it was handed down to us [says Draper.]”[8]

The glimmering lamp of knowledge was sustained when it was all but ready to die out. By the Arabians it was handed down to us [says Draper.]”[8]

A brief statement, which means everything. Scott, Haskins and Metlitzki help in this respect to highlight the dire state of learning and civilisation in the West, including England, and how it was the Muslims who kept them before they passed on some such light of knowledge.

Tenth century Andalusia [Scott tells us,][9] was traversed in every direction by magnificent aqueducts; Cordova was a city of fountains; its thoroughfares, for a distance of miles, were brilliantly illuminated, substantially paved, kept in excellent repair, regularly patrolled by guardians of the peace. In London, in contrast, there were no pavements until the fourteenth; at night the city was shrouded in inky darkness; that it was not until the close of the reign of Charles II (17th century), that even a defective system of street lighting was adopted in London. The mortality of the plague is a convincing proof of the unsanitary conditions that everywhere prevailed; the supply of water was derived from the polluted river or from wells reeking- with contamination.

Tenth century Andalusia [Scott tells us,][9] was traversed in every direction by magnificent aqueducts; Cordova was a city of fountains; its thoroughfares, for a distance of miles, were brilliantly illuminated, substantially paved, kept in excellent repair, regularly patrolled by guardians of the peace. In London, in contrast, there were no pavements until the fourteenth; at night the city was shrouded in inky darkness; that it was not until the close of the reign of Charles II (17th century), that even a defective system of street lighting was adopted in London. The mortality of the plague is a convincing proof of the unsanitary conditions that everywhere prevailed; the supply of water was derived from the polluted river or from wells reeking- with contamination.

[In Muslim Spain, then, Scott pursues,] the annual receipts of the state from all sources under Abd-al-Rahman III, in the first half of the tenth century exceeded three hundred million dollars (late 19th century value); the revenues of the English Crown at the close of the seventeenth century were fifteen million. The inhabitants of England at the death of Elizabeth were about four million; the population of Muslim Spain six centuries previous to that date could not have been less than thirty million. In 1700, London, the most populous city of Christian Europe, was only half as large as Cordova was in 900, when Almeria and Seville had each as numerous a population as the capital of the British Empire eight hundred years afterwards.”[10]

Medieval Muslim visitors to Christian towns complained-as Christian visitors now to Muslim towns do of the filth and smell of the “infidel cities.”[11] At Cambridge, now so beautiful and clean, sewage and offal ran along open gutters in the streets, and ‘gave out an abominable stench, so… that many masters and scholars fell sick thereof.’[12] In the thirteenth century some cities had aqueducts, sewers, and public latrines; in most cities rain was relied upon to carry away refuse; the pollution of wells made typhoid cases numerous; and the water used for baking and brewing was usually-north of the Alps-drawn from the same streams that received the sewage of the towns.[13]

At the dawn of the eleventh century, [resumes Scott] the Muslim dominions of Sicily and Spain presented a picture of universal cultivation and consequent prosperity, where industry was promoted and idleness was punished; where an enlightened spirit of humanity had provided asylums within whose walls the infirm and the aged might pass their remaining days in comfort and peace. Six hundred years afterwards what are now the richest and most valuable agricultural districts of Great Britain were unclaimed and uninhabitable bog and coppice, abandoned to game and frequented by robbers; and one-fourth of the inhabitants of England, incapable of the task of self-support, were during the greater part of the year dependent upon public charity, for which purpose a sum equal to one-half of the revenues of the crown was annually disbursed. In the middle of the tenth century there were nine hundred public baths in the capital of Moorish Spain; in the eighteenth century there were not as many in all the countries of Christian Europe.[14]

Figure 2. Some of the Islamic/Arabic dirhams found at Torksey [Torksey is a small village in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England.] Photograph: © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (Source)

As for learning, the situation in England, as elsewhere in Western Christendom, was in a lamentable condition. King Alfred had complained of the English ignorance of Latin, the language of literature and moral culture.[15]The chief centres of culture, Haskins tells us, were the monasteries ‘islands in a sea of ignorance and barbarism saving learning from extinction in Western Europe at a time when no other forces worked strongly to that end.’[16] `When we remember,’ Lane Poole notes, `that the sketch we are about to extract from the records of Arabian writers concerning the glories of Cordova, relate to the tenth century, when our (English) Saxon ancestors dwelt in wooden hovels and trod upon dirty straw, when our language was unformed, and such accomplishments as reading and writing were almost confined to a few monks, we can to some extent realize the extraordinary civilisation of the Moors.’[17]

From what his friends told him of England, Adelard of bath (fl.1106), the first English scientist, on whom plenty more further down, gathered that:

Violence ruled among the nobles, drunkenness among the prelates, corruptibility among the judges, fickleness among the patrons, and hypocrisy among the citizens; mendacious promises were given lightly, friends were invidious, and almost all whom one met courting favours.”[18]

The coming anarchy of the reign of Stephen was on its way. Nothing seemed more distasteful to Adelard than to submit to this `misery’. Being unable to avert `this moral degeneration,’ he decided to ignore it, holding a unique consolation-his enthusiasm for Arabum studia’ (Arab Studies).[19]

Adelard returned to England `in the reign of Henry, son of William,” having left it before 1100 to spend seven years learning in the Muslim East. His Quaestiones Naturales which he composed for the benefit of `his nephew,’ praises Muslim learning, to contrast with his feeling of misery about learning in England. The Quaestiones Naturales, in the form of a dialogue between him and his imaginary nephew, is essentially a report of Adelard’s grand tour and reflects ‘his excitement at the new scientific outlook of the Muslims which had left the Latin schools far behind.’[20]

Nothing contrasts more the discrepancies in learning as the place of books. When Muslim libraries abounded with books, some containing even tens of thousands, and where students, scholars and any curious mind found a place, there was hardly anything of worth in any part of the Christian West, not just the British Isles.[21] Even by the early so-called Renaissance (around the late 15th century) few books existed in Christian Europe excepting those preserved in monasteries; the royal library of France consisted of nine hundred volumes, two-thirds of which were theological works; their subjects were limited to pious homilies, the miracles of saints, the duties of obedience to ecclesiastical superiors,—their sole merit consisted in the elegance of their chirography and the beauty of their illuminations.[22] Even the illustrious Santa Maria de Ripoll, at its height under Abbot Oliva (1008-46), when we have a catalogue of its notable library of two hundred and forty six titles.[23] In England itself, in the highest seat of university learning, Oxford, we are told its ‘library’, before the year 1300, consisted only of a few tracts, chained or kept in chests in the choir of St. Mary’s Church.[24] Warton, in fact enlightens us more on this subject:

Although the invention of paper, at the close of the eleventh century, contributed to multiply manuscripts, and consequently to facilitate knowledge, yet even so late as the reign of our Henry the sixth, I have discovered the following remarkable instance of the inconveniencies and impediments to study, which must have been produced by a scarcity of books. It is in the statutes of St. Mary’s college at Oxford, founded as a seminary to Oseney Abbey in the year 1446. “Let no scholar occupy a book in the library above one hour, or two hours at most; so that others shall be hindered from the use of the same.” The famous library established in the university of Oxford, by that munificent patron of literature Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, contained only six hundred volumes.’ About the commencement of the fourteenth century, there were only four classics in the royal library at Paris. These were one copy of Cicero, Ovid, Lucan, and Boethius. The rest were chiefly books of devotion, which included but few of the fathers: many treatises of astrology, geomancy, chiromancy, and medicine, originally written in Arabic, and translated into Latin or French: pandects, chronicles, and romances. This collection was principally made by Charles the fifth, who began his reign in 1365. This monarch was passionately fond of reading, and it was the fashion to send him presents of books from every part of the kingdom of France. These he ordered to be elegantly transcribed, and richly illuminated; and he placed them in a Tower of the Louvre, from thence called, La Toure de la Librairie. The whole consisted of nine hundred volumes. They were deposited in three chambers which, on this occasion, were wainscotted with Irish oak, and cieled with cypress curiously carved. The windows were of painted glass, fenced with iron bars and copper wire. The English became masters of Paris in the year 1425. On which event the Duke of Bedford, regent of France, sent this whole library, then consisting of only eight hundred and fifty-three volumes, and valued at two thousand two hundred and twenty-three livres, to England, where perhaps they became the ground-work of Duke Humphrey’s library just mentioned. Even so late as the year 1471, when Louis the eleventh of France borrowed the works of the Arabian physician Rhasis from the faculty of medicine at Paris, he not only deposited by way of pledge a quantity of valuable plate, but was obliged to procure a nobleman to join with him as surety in a deed by which he bound himself to return it under a considerable forfeiture.”[25]

Under Muslim rule, it was difficult to encounter even a Muslim peasant who could not read and write; during the same period in Europe many great personages could not boast these accomplishments. And from the 9th to the 13th century, the Spanish Muslims possessed an educational system ‘not inferior to the most improved ones of modern times.’[26]

It was at the peak of such contrasts, when Cordova was the city of light in the midst of darkness, that there descended to that same city European envoys, soon to turn into early European scholars, one man in particular from Lorraine, where the revival of the West, including of Britain, would begin.