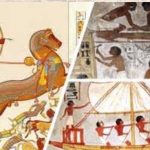

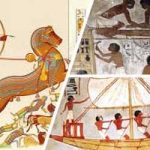

The best-known examples of these models come from the tomb of Meketre of the early Middle Kingdom. These are small dioramas which detail the brewing process at that time. The models supplement letters, receipts, and other written works in depicting how beer was brewed and by whom. Strudwick notes that “although beer was produced daily in most ancient Egyptian households, there was also large-scale production in breweries for distributing rations to town-dwellers, taverns or ‘beer houses’, wealthy individuals, and state employees” (410).

Every brewer had her or his own particular specialty, with some brews known for higher alcohol content and others for a certain flavor. According to Strudwick, “the most common kind of beer was a rich, slightly sweet ale, rather like brown ale, but lighter beers similar to a modern lager were created for special occasions” (411). In either case, as in the modern day, brewers followed basically the same procedure.

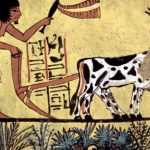

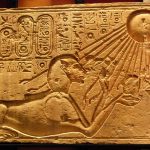

At first, around the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, beer was brewed by mixing cooked loaves of bread in water and placing the mixture in heated jars to ferment. The use of hops was unknown to the Egyptians as was the process of carbonation. To a modern-day beer drinker, an Egyptian brew would taste more like a fruit drink than the familiar beverage. Dates and honey were added for sugar, taste, and higher alcohol content, and then yeast in order to increase fermentation. This beer was a thick, dark red brew which perhaps suggested the beer originally dyed by Ra to calm and transform Sekhmet.

By the time of the New Kingdom barley and emmer (wheat) were used which were mixed with water to create a mash which was then poured into vats and heated to ferment. This mixture was then strained and different herbs and fruits added for the flavoring of the various types of beer. According to Strudwick, “fermentation of everyday beer took a few days, producing a mixture fairly low in alcohol” and “the outcome was a thick, brothy liquid that had to be filtered through a basket before being drunk” (410). Once strained, the beer was sealed in ceramic jugs and stored, often underground in a process similar to later lagering.

In the New Kingdom, when emmer and barley were used, the use of dates and honey decreased in the production of common beer and were only used for higher quality brews for special occasions. Beer with a high alcohol content was favored for banquets and festivals and, in fact, a party was rated a success depending on the level of the participants’ intoxication and the amount of beer consumed. The highest quality beer, of course, was brewed for the king and the nobility and flavored with honey which was associated with the gods. The beer found in the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun, for example, was honey beer similar to the later European mead.

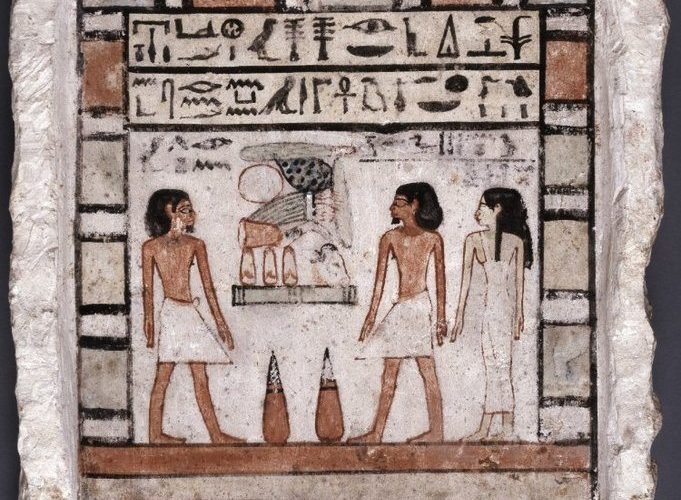

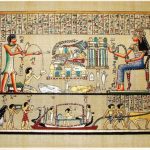

From the Middle Kingdom onwards, beer was increasingly a state-run industry, although people still brewed their own in their homes. This beer continued to be amber in color but not as thick; as shown by residue found in the bottom of vats and also through the beer found in Tutankhamun’s tomb and others. Just as beer was considered a staple for Egyptians in life, so was it considered a necessary offering for the dead; beer, therefore, became one of the most common grave goods placed in tombs for those who could afford to part with it. Since beer was was a common form of payment, including jars of the brew in a tomb would be comparable to burying one’s paycheck with the deceased.

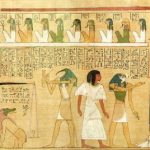

Besides the use of beer as part of one’s daily meals and at festivals, the drink featured prominently at banquets and funerals. Funerals were a celebration of the life of the departed and also a send-off for the soul on the continued journey into the afterlife. Once the formal ritual of the funeral was concluded, family and guests would gather, often outside the tomb under a tent, for a picnic-banquet at which the food the deceased had enjoyed in life would be served along with a quantity of beer and, sometimes, wine.

Beer was served to guests from pitchers and poured into ceramic cups from which guests drank without the use of straws or strainers. Strudwick notes that “the quality of beer depended on both the skill of the brewer and the sugar content: the more sugar that was added to the fermentation, the stronger the beer” (411). The beer served at funerals would have been higher in alcohol content than a regular brew. The same beer enjoyed by the guests would have earlier been placed in the tomb of the departed.

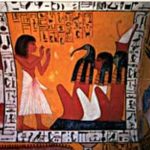

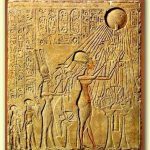

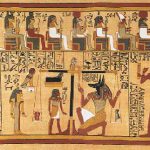

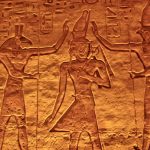

Just as beer was offered to the souls of the dead, it was considered the best offering to the gods. Temples brewed their own beer which was given to the statue of the god in the inner sanctum to gladden his or her heart just as it did humanity’s. Food and drink would be placed before the deity’s statue, which contained their spirit, and the nutrients absorbed supernaturally. The meal would then be taken away and given to the temple staff. Osiris had given the people the knowledge of beer, and the people showed their gratitude by offering in return the fruits of that knowledge: beer, the drink of the gods.