Origins

Pharaoh Ay is believed to have been a native Egyptian commoner by birth and born in Akhmim. He is thought to have been the son of Yuya, an Egyptian priest who also held various other offices in the land.

© Ashley Van Haeften – Birth name of Ay

© Ashley Van Haeften – Birth name of Ay

This conjecture is speculative only and is based on physical similarities between the two men; no documentation or DNA testing has proven the theory. Pharaoh Ay is also thought to have been partially of Syrian ethnicity and may have been brother to Tiye, who was one of Amenhotep III’s wives.

Ay and his first wife are thought to have been Queen Nefertiti’s parents, which would have made him the grandfather to Tutankhamun. Part of this speculation is based on a title he used, “It Netjer” which means “father-in-law of the king” or “God’s Father.” Again, there is no documentation or other evidence to support this theory, it is speculative only.

Role in the Amarna Period

The Amarna Period is significant in Egyptian history because the nation shifted from the worship of many gods to the worship of one god, Aten, who was the sun god. The royal palace was moved to Akhet-Aten and Amun, the name of the old religion’s primary god, was removed from buildings and monuments.

From inscriptions found on a box intended for his tomb, Pharaoh Ay is thought to have achieved the following ranks:

- Overseer of all the horses of his majesty

- Troop Commander

- Overseer of horses

- Fan-bearer on the right side of the king

- Acting scribe of the king

Overseer of all the horses of his majesty was the highest rank in the army’s charioteering division. Chariots were considered the primary weapons of the army and both the vehicles and the horses were extremely valuable.

The position of right-hand fan bearer indicated that he had the king’s ear and was another extremely important position in the court. When Ay subsequently became pharaoh, he incorporated this name into his title.

© Captmondo – Relief Cartouche of Ay

© Captmondo – Relief Cartouche of Ay

Two different theories exist to explain the rise of a commoner to such exalted positions. One theory postulates that, as mentioned above, he was the son of Yuya and therefore Amenhotep III’s brother-in-law. Yuya was one of Amenhotep’s senior military officers and speculation is that Ay followed the same direction and inherited his father’s duties when Yuya died.

The other theory is that Ay had a daughter who married Akhenaten and therefore had access to offices not usually given to commoners. Neither theory has weight over the other and documentation is scarce to support either theory.

Relationship with Tutankhamun

After Akhenaten’s death, Ay remained as advisor to the young Tutankhamun and evidence indicates that Ay was highly influential in abolishing the practice of monotheism and returning Egypt to its worship of many gods. Since Ay was Tut’s grandfather, the young Tut probably had little reason to distrust him and many reasons to conclude that Ay had Tut’s best interests at the forefront.

Although young King Tutankhamen, according to modern testing, appears not to have been murdered, which was previously thought, he led a difficult life and reign, and the presence of his grandfather may or may not have been a help.

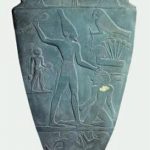

© Tjflex2 – Plaque at Thebes, depicting King Tut

© Tjflex2 – Plaque at Thebes, depicting King Tut

Reign of Pharaoh Ay

Pharaoh Ay reigned briefly, from either 1331 to 1327 BC, or from 1327 to 1323 BC, depending on the source; absolute dates have not been established. Some speculate this Ay’s reign could have been as long as nine years because his temple and monuments were eliminated by his unintended successor, Horemheb.

Nevertheless, it was a brief reign enabled only by his marriage to King Tut’s widow. Under Egyptian law, a commoner could not assume the throne unless married to royalty first.

Ay officiated at Tut’s burial and quickly assumed the role of heir, outmaneuvering Horemheb in his bid for the throne. Ay quickly married Tut’s widow Ankhesenamun, thereby cementing his position as pharaoh. Although Ay had served for more than 25 years under Akhenaten and Tutankhamen, his common birth would otherwise have prohibited his rise to the throne.

A letter purported to be from Ankhesenamun to the enemy Hittite king Suppiluliumas urgently requests that he send her one of his sons so that she doesn’t have to marry Ay, who by this time was at quite an advanced age, approximately 70 years old. Although Suppiluliumas reluctantly agreed, his son was killed en route to the marriage and Ay is thought to have been responsible.

Upon becoming pharaoh, Ay began to persecute followers of Akhenaten and that seems to be the focus of his short, four-year reign. After Ay became pharaoh, Ankhesenamun disappears and nothing further is heard about her.

© woodsboy2011 – Relief of Ay and his Wife

© woodsboy2011 – Relief of Ay and his Wife

Death of Pharaoh Ay

Ay had intended that Nakhtmin, who was either a natural son or an adopted one, be his successor. However, Horemheb eliminated his rival’s claim and assumed the throne. Since Horemheb also eliminated much that existed of his predecessor Ay, little more is known of him.

Horemheb instigated a campaign of expunging the monotheistic references, including those who endorsed it. He desecrated Ay’s tomb and annihilated his sarcophagus.

Pharaoh Ay’s Successors

Horemheb became the last of the 18th dynasty pharaohs and ushered in the 17th dynasty, also known as one of the second intermediate period dynasties. Rulers of this period were:

Archaeological Evidence

A wedding ring discovered in 1920 has the abutting cartouches of both Ankhesenamun and Ay inscribed inside it; this indicated that a marriage ceremony had taken place. The hastiness of the ceremony is indicated by pictures of Ay officiating at Tut’s death and wearing the blue crown, which indicates his claim to the throne.

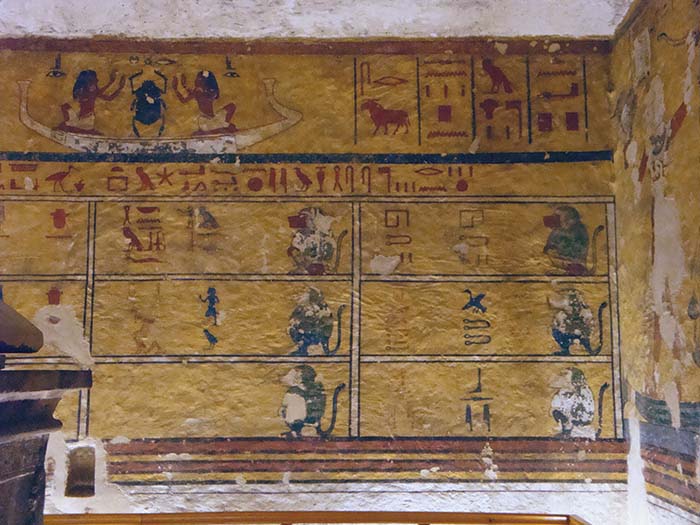

Inside the tomb of King Tut, a picture shows Ay performing the opening of the mouth ceremony, which was usually performed either by a high priest or the new pharaoh.

Ay’s royal tomb is one of two in the West Valley of the Kings. It was damaged after Ay’s burial; all of his images and his name were eradicated.

Although Ay’s sarcophagus was briefly on display at the Cairo museum during his tomb restoration, it has been returned to his tomb, although it was installed backwards. His mummy has never been located and it’s speculated that Horemheb had it destroyed so that Ay could not achieve his place in the afterlife.