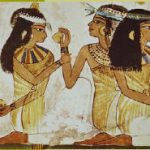

When it comes to legal rights, Herodotus wasn’t completely off the mark in his assessment of Egypt as the polar opposite of Greece. In ancient Greece, women possessed no legal standing and had to appoint a male to represent them in legal affairs. Upper-class Egyptian women enjoyed far more rights. One book of instruction for ancient Egyptians written by the vizier Ptahhotep during the Old Kingdom (2686 – 2181 B.C.) even advised men to never take their wives to court.

Women were able to represent themselves in court, motion for divorce, own and manage property, free slaves and sue other people. In the eyes of the law, elite men and women were virtually equal.

Marriage and divorce proceedings also were surprisingly progressive, even in comparison to today’s Western standards. The most common family unit consisted of a husband and wife, the husband’s widowed mother and unwed sisters. When the time came for weddings, the government and temples fulfilled no function, and the affairs remained private, relatively casual events. Nevertheless, the unions often resulted from agreements between the husband and the brides’ parents.

Before tying the knot, premarital sex was socially acceptable, and divorce was neither difficult to attain nor uncommon .

When a couple split up, the law didn’t leave the woman high and dry, either: Divorced women took their dowry and any property they owned with them.

Although upper-class women enjoyed these legal privileges, they didn’t extend to the lower ranks of the public. Egyptian law was gender-neutral — but not class-neutral. Social status determined one’s legal status in ancient Egypt. The patriarchal structure of the time dictated that a female’s social status be controlled by her father while unmarried and her husband after marriage. Consequently, a woman’s liberties were linked inextricably to a male counterpart somewhere along the line.

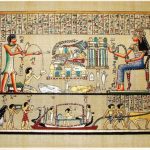

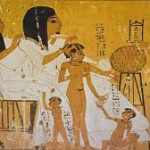

Women also had designated parts to play in society. The most common title for a married woman was “mistress of the house.” Wealth afforded women more opportunities for participation in public life, such as participating in a jury or becoming a priestess; but overall, married women presided over their own households only. The closest that most royal women ever got to the throne was the position of regent, which Hatshepsut held before becoming pharaoh.

Lower-class women got out of the house more often than their upper-class peers out of necessity. They farmed the fields, produced textiles, worked as domestic servants and labored on construction sites. Poor women also held most jobs as dancers, musicians and other entertainers for royalty. Men traditionally filled all artisan jobs.

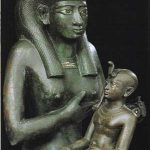

Female subservience even extended into the religious realm. Ancient Egyptians worshipped scores of gods and goddesses alike, with a Great Mother goddess in the form of Hathor or Isis. Yet, in the mythology surrounding the birth of gods and goddesses, the creator Atem first sneezed into existence the god Shu, followed by the goddess Tefnut .

Ancient Egyptian society was an intriguing hodgepodge of women’s progressive rights and rigorous restrictions. The popular conceptions of strong Egyptian women, especially Cleopatra, have likely promoted the curious notion of a feminist utopia along the Nile. On the contrary, archeological evidence confirms that ancient Egyptian feminism is as false as Hatshepsut’s kingly beard.