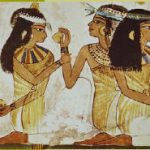

Current knowledge of Ancient Egypt indicates that Egyptian women were the equal of men under the law (unlike Greco-Roman or Mesopotamian women during the same period). Thus, they could own land, manage their own property and represent themselves in court cases. They could sit on juries and testify in trials. At the same time, they were also subject to the same legal penalties as men. She could divorce, initiate a lawsuit to recover the assets of the household and win the case, which did not prevent her from remarrying, as shown by the archaeological data on the Jewish community of Elephantine found in the Elephantine papyri.

Marriages were often arranged by the fathers of the bride and groom, but it was not rare for spouses to make their own choice. Normally the fathers of the bride and groom would arrange a pre-nuptual contract between the future spouses. The purpose of the pre-marital contract was to specify what allowance the wife would be entitled to receive from her husband, as well as what presents the groom was expected to give to his wife and her parents. The contract specifies any property or goods that the wife brings with her, and they remain hers in the case of divorce. There was no dowry expected from the bride’s father, another significant difference with other societies in the region.

By marrying, the Egyptian woman kept her name with the added-on surname “wife of X”. Marriage appears to have been perceived as a natural state, and it seems that it did not result from an administrative process or a religious event; it often embodies the will of a man and a woman to live together, which does not prevent the possible existence of a material marriage contract in the future, as was often the case elsewhere. As Christiane Desroches Noblecourt emphasizes, “marriage and eventually divorce are events sanctioned in the family environment only by the will of the spouses, without any intervention by the Empire’s bureaucracy”; the bride and groom pronounced the phrases: “I make you my wife” and “You make me your wife”.

Men were obligated to guarantee the well-being of their spouse in material ways. The scribe Ani (during the New Kingdom period) advised future spouses :

- If you are wise, keep your house, love your wife without interference, feed her properly, dress her well. Caress her and fulfill her desires. Do not be brutal, you will obtain much more from her through respects than through violence. If you reject her, your household goes down the drain. Open your arms, call to her; witness your love to her.

Certainly, things did not always proceed in an ideal fashion and divorce existed. It began on the initiative of one or the other spouse. If the initiative came from the husband, it had to cede part of his goods to his wife; if the women took the initiative, she was held to the same obligation but to a lesser degree. Recourse to a tribunal was possible in the case of a contested divorce between the spouses, although the Empire’s bureaucracy did not intervene in the act of marriage.

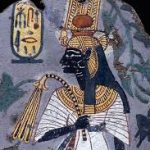

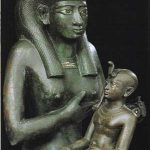

The great hymn to Isis written in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri expresses this equality between men and women, addressing the goddess with “the honor of the feminine sex” — “it is you, the mistress of the earth … you have given women power equal to that of men”.

Christiane Desroches Noblecourt :

- Egyptian women, the mother that one respected above all, the women subject to a strict moral code, but granted a great freedom of expression — her entire legal capacity, her shocking financial independence, the impact of her personality in family life and the management of common belongings and her own belongings. The insistence of the Egyptian moralists to remind men of their duties towards their wives lends itself to speculation that it was not rare in practice that men abused their position.