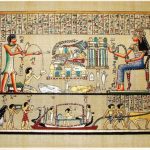

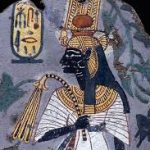

Egyptian culture empowered women from the time of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE) through the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) as evidenced by powerful female rulers such as Neithhotep in the First Dynasty through Cleopatra VII in the Ptolemaic Dynasty. There does not seem to have been the necessity of a particular cult in the New Kingdom to elevate the feminine since women had been participating almost equally in Egyptian society for thousands of years by then.

For example, from the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) women held the position of ‘sealers’ which was among the most important jobs one could have. In the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) women were still in this position and the practice continued into the New Kingdom. Robins explains:

Sealing was one of the commonest duties of men throughout the bureaucracy because, in the absence of locks and keys, seals were used to safeguard property. A sealer carried the authorized seal with which to secure containers and storerooms against unauthorized entry.

Women as sealers are evidence of their equality with men throughout Egypt’s history. Even though, as in the home, men were considered the dominant authority figures, women could obviously hold the same position as long as they were not supervising and giving orders to men.

Even this point not does hold true in every era of Egypt’s history, however, as it seems the female physician Pesehet (c. 2500 BCE) was a teacher at the medical school at Sais and the position of God’s Wife of Amun, which became increasingly important in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, was the female counterpart of the male High Priest. Female physicians would have seen both male and female patients, female seers would have interpreted the dreams and omens of males as well as females, and female dentists would have worked on alleviating the tooth pain of men as often as women.

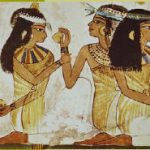

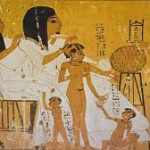

Women also were the first beer brewers and textile manufacturers in Egypt and continued to manage workshops and breweries even when men took over the day-to-day operation of the business. Paintings, inscriptions, and statuary depict women working in as well as supervising over manufacture and distribution of goods. Women of means could also be the Mistress of the House meaning they owned their own land, produce, and means of harvest and distribution.

Those who had acquired particularly impressive skills in home management could make a living as Household Managers in the homes of the wealthy and nobility. These women were responsible for supervising the servants and making sure that every job was done to satisfaction as well as stocking the home with supplies and organizing official dinners and banquets. The title of Keeper of the Dining Hall was especially important to the upper-class nobility who entertained foreign diplomats and other dignitaries as the banquet prepared and served would need to be perfect in every way.

Women may have worked their way up to these kinds of positions from the lower status of maid, servant, or cook. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley writes:

An Egyptian woman of good character could always find employment as a servant; the lack of modern conveniences, such as electricity and plumbed water, meant that there was a constant demand for unskilled domestic labour. A servant’s wages were relatively cheap and most middle- and upper-class homes had at least one maid who could be trained in domestic skills while helping out with the more arduous household chores.

Girls would enter the service at a young age, sometimes around 13, and if they proved themselves to be conscientious and loyal, could move up to a higher position. These women were vitally important to the maintenance of a home, and numerous letters and inscriptions make this clear. A common practice in ancient Egypt was writing letters to the dead asking for help in some matter. These often assumed a problem was being caused by some supernatural entity, usually an angry ghost or spirit whom the deceased could reason with or confront.

In one of these letters to the dead from a wife to her departed husband, the woman asks for his intercession on the part of a serving girl who is ill. She writes:

Can you not fight for her day and night with any man who is doing her harm, and any woman who is doing her harm? Why do you want your threshold to be made desolate? Fight for her again – now! – so that her household may be re-established and libations poured for you. If there’s no help from you, your house will be destroyed; don’t you know that it is this serving maid who makes your house amongst men? Fight for her! Watch over her!

A good servant was often considered a member of the family, and in some eras, a childless couple would adopt a servant as heir to ensure that their mortuary rites were performed correctly and that there would be someone to leave their estate to. In the above letter, the wife threatens the husband with cutting off his food and drink offerings (“why do you want your threshold to be made desolate?”) if he does not intercede on the girl’s behalf. This was a very serious threat because it was thought the dead required daily sustenance in the afterlife and it shows how much this serving girl meant to the author of the letter.

If a woman did not care for domestic work, she could be an entertainer. Women are recorded as musicians, singers, and dancers whether publicly or for temple rituals. Women could also be sacred singers who accompanied and assisted the God’s Wife of Amun at Thebes and, in some instances, succeeded to that position. In order to become a God’s Wife, the woman would need to know how to read and write and so, although a number of scholars claim that women lacked this skill, there seem to have been more of them than are credited.

Evidence for women’s literacy comes from ostraca (clay pot shards) with notes on them relating to childbirth, children, dressmaking, laundry, and other domestic issues. These ostraca are the ancient equivalent of the modern day to-do list in some cases and, in others, are either protective charms or execration texts. Whatever form they take, there is no doubt they were written by women.

Women were denied high positions such as vizier and, save for some notable exceptions, the monarchy, but they certainly had greater opportunities for personal advancement and financial gain than their sisters in neighboring countries. Women were essential figures as midwives, seers, and tattoo artists – though it is unclear if they were paid for these services – but also feature prominently in positions most often held by males. The women of ancient Egypt were largely the directors of their own fate, and in many cases, the only limit to their success was their own talent and imagination.