The treatments prescribed usually combined some practical application of medicine with a spell to make it more effective. For example, a roasted mouse ground into a container of milk was considered a cure for whooping cough, but a ground mouse in milk taken after reciting a spell would work better. Mothers would bind their children’s left hand with a sanctified cloth and hang images and amulets of the god Bes in the room for protection, but they also would recite the Magical Lullaby which drove off evil spirits.

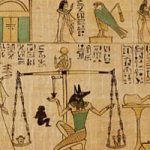

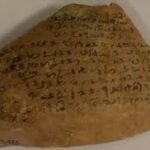

At the same time, there are a number of prescriptions which make no mention of magical spells. In the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) a prescription for contraception reads: “grind together finely a measure of acacia dates with some honey. Moisten seed-wool with the mixture and insert into the vagina” (Lewis, 112). The Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE) focuses on surgical treatment of injuries and, in fact, is the oldest known surgical treatise in the world. Although there are eight magical spells written on the back of the papyrus, these are thought by most scholars to be later additions since papyri were frequently used more than once by different authors.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is the best known for practical procedures addressing injuries, but there are others which offer the same kind of advice for disease or skin conditions. Some of these were obviously ineffective – such as treating eye ailments with bat’s blood – but others seem to have worked. Invasive surgery was never widely practiced simply because the Egyptian surgeons would not have considered this effective. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick explains:

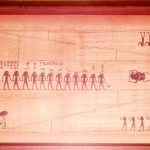

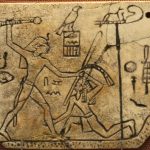

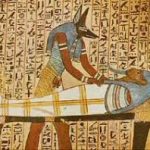

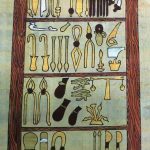

Because of the limited knowledge of anatomy, surgery did not go beyond an elementary level and no internal surgery was undertaken. Most of the medical instruments found in tombs or depicted on temple reliefs were used to treat injuries or fractures which were possibly the result of accidents incurred by workers on the pharaohs’ monumental building sites. Other implements were used for gynaecological problems and in childbirth, both of which were treated extensively in the medical papyri. (454)

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE) is the oldest document of its kind dealing with women’s health. Although spells are mentioned, many prescriptions have to do with administering drugs or mixtures without supernatural assistance, as in the following:

Examination of a woman bed-bound, not stretching when she shakes it,

You should say of it ‘it is clenches of the womb’.

You should treat it by having her drink 2 hin of beverage and have her spew it up at once. (Column II, 5-7)

This particular passage illustrates the problem in translating ancient Egyptian medical texts since it is unclear what “not stretching when she shakes it” or “clenches of the womb” mean precisely, nor is it known what the beverage was. This is often the case with prescriptions where a certain herb or natural element or mixture is written as though it is common knowledge needing no further explanation. Beer and honey (sometimes wine) were the most common drinks prescribed to be taken with medicine. Sometimes the mix is carefully described down to the dose, but other times, it seems it was assumed the doctor would know what to do without being told.

Conclusion

As noted, the physicians of ancient Egypt were considered the best of their time and frequently consulted and cited by doctors of other nations. The medical school at Alexandria was legendary, and the great doctors of later generations owed their success to what they learned there. In the present day, it may seem quaint or even silly for people to believe that a magical incantation recited over a cup of beer could cure anything at all, but this practice seems to have worked well for the Egyptians.

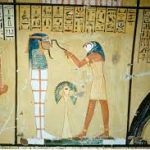

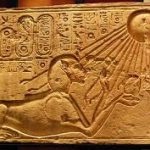

It is entirely possible, as a number of scholars have suggested, that the success of the Egyptian doctor epitomizes the placebo effect: people believed their prescriptions would work, and so they did. Since the gods were so prevalent an aspect of Egyptian life, their presence in curing or preventing disease was no great leap of faith. The gods of the Egyptians did not live in the far-off heavens – although they certainly occupied that space as well – but on the earth, in the river, in the trees, down the road, in the temple in the city’s center, at the horizon, noon, sunset, through life and on into death. When one considers the close relationship the ancient Egyptians had with their gods it is hardly surprising to find supernatural elements in their most common medical practices.