3. Three Muslim Scholars: Al Dimashki; Al Muqaddasi, and Ibn Khaldun:

As noted above, primary Muslim sources are the first recourse for any understanding of the subject. This is highlighted by the next few instances

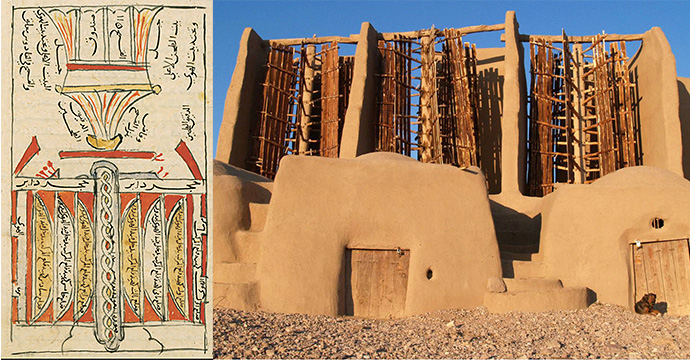

We begin with Al Dimashki,[101] in respect to a major issue that has yet not been addressed in this essay: the pioneering Islamic role in harnessing the forces of nature for economic purpose, specifically in the construction of windmills. Al Dimashki offers us one of the best descriptions together with an illustration.[102]It reads thus in translation:

“When they have carried out the construction of the two rooms as shown in the illustration, they make four embrasures in the lower room like the embrasures in the walls (aswar), only here the embrasures are the other way round, as their broad part is turned to the outside and their narrow part to the inside, [thus forming] a channel for the air so that through it the air enters inside with force as in the goldsmith’s bellows. The broad end is situated towards the mouth and the narrow one towards the inside so that it is more suitable for the entry of the air which enters into the room of the mill, from whichever area the wind may be blowing.”[103]

Figure 3. (Left) A 14th-century manuscript by Al-Dimashqi shows a cross-section of a typical windmill whose vertical vanes rotate around a vertical shaft, (Right) Windmills in the Iranian region of Nishtafun Right (Source)

Another geographer, Al Himyari, from Muslim Spain (writing in 866/1461) mentions, among the special features of the port of Tarragona, the existence of mills driven by wind power.[104]

In the following are addressed a variety of social issues with focus on al Muqaddasi and Ibn Khaldun. Before beginning with al Muqaddasi who in time preceded Ibn Khaldun by a few centuries, necessity requires us to mention that although al Muqaddasi was excellent at description, in terms of putting social theories or analysis, here, the master remains Ibn Khaldun. It was he who shaped the whole subject, laying the foundations upon which his successors built, not just in terms of methodology and contents, but also structure and approach. As Toynbee notes:

Islamic social scientists of Islam prior to Ibn Khaldun would hence, if a rigorous modern methodology or approach were pursued, not be included in the same realm as modern social scientists. Their writing often evolved outside a structured methodology. This, however, is the case of every science, beginning first with rough edges, and then gradually being refined by the time and labours of its practitioners.

Al-Muqaddasi

Al-Muqaddasi (or Al-Maqdisi), (b. 946-d. end of 10th century), originally from Al-Quds (Jerusalem), hence his name, is by far one of the most instructive of all early writers on Islamic society.[106] His works can generally, be found under the subject of geography. His best known treatise Ahsan at-Taqasim fi Ma’arifat Al-Aqalim (the best divisions in the knowledge of the Climes) was completed around 985 CE.[107] A good summary of it is given by Kramers,[108] extracts of which can be found in Dunlop‘s Arab Civilisation.[109] In this work, Al-Muqaddasi gives an overall view of the lands he visited, and gives the approximate distances from one frontier to the next. Then, he deals with each region separately. He divides his work in two parts, first enumerating localities and providing adequate description of each, especially the main urban centres. He then proceeds to other subjects: population, its ethnic diversity, social groups… moves onto commerce, mineral resources, archaeological monuments, currencies, weights, and also the political situation. This approach is in contrast with his predecessors, whose focus was much narrower; Al-Muqaddasi wanted to encompass aspects of interest to merchants, travellers, and people of culture.[110] Thus, it becomes no longer the sort of traditional ‘geography’, but a work that seeks to understand and explain the foundations of Islamic society, and not just that, the very functioning of such society. Out of this, excellent information, regarding many subjects can be gleaned.

Water as a social indicator:

On the subject of water management and hydraulic technology, much can be learnt from Al-Muqaddasi’s treatise. In Egypt, the description of the Nilometer attracts most attention:

In Biyar, in the Al-Daylam region, he notes the drier conditions, pointing out that water is distributed by water clock, whilst the millstones are below ground, and the water flowing down. This being the desert, he observes, there is no other choice.[112] And in Al-Ahwaz, in Khuzistan he notes:

Still on water, but on a more anecdotal note, Al-Muqaddasi makes the following observation:

Fiscal Issues and Finance

Currency, its uses, and its users, as well as its fluctuations, constitutes a major area of interest for Al-Muqaddasi. Dinar, Dirhem, their multiples, and sub-multiples, as well as each region‘s local currencies are dealt with in their most intricate functions. Thus, for the Maghrib region, Al-Muqaddasi states:

There is also the small rub`, (quarter of a dinar); these two coins pass current by number, [rather than the weight]. The dirham also is short in legal weight. A half dirham is called a qirat; there is also the quarter, the eighth part, and the sixteenth part which is called a kharnuba. All of these circulate by number [rather than by weight], but their use thus does not bring any reduction in price. The sanja (counterpoise weights) used are made of glass, and are stamped just as described about the ratls.

The ratl of the city of Tunis is twelve uqiya (ounce), this latter being twelve dirhams (weight).”

Exchanges from one currency to the other also receive attention from the author, as well as their emission, control, regulations, and much else. The wealth of those involved in currency dealing is also garnered.

Figure 4. Umayyad coins, 693CE (Source)

Prices, their fluctuations, varying in relation to size and wealth for every market place, are considered; Cairo, Al-Muqaddasi notes, has such low prices as to greatly surprise him.

Al Muqaddasi could hardly ignore taxes, being himself a trader on occasions, finding them light and bearable in some places, and perverse and disastrous in others. Thus, in parts of the Arab peninsula, he observes that:

In Uman a dirhem is levied on every date palm tree. I have found in the work of Ibn Khurradadhbih that the revenue of Al-Yaman is six hundred thousand Dinars; I do not know what he means by this, because I did not see it in Kitab Al-Kharaj (the Book of Tribute). In fact, rather, it is well known that the Peninsula of the Arabs is on a tithing system. The province of Al-Yaman formerly was divided into three departments, a governor over Al-Janad and its districts, another over Sanaía and its districts, and a third over Hadhramawt and its districts. Qudama bin Jaíafar Al-Katib has noted that the revenue of Al-Haramayn (the two sacred cities) is one hundred thousand dinars, of Al-Yaman six hundred thousand dinars, of Al-Yamam and Al-Bayrayn five hundred thousand dinars, and of Uman three hundred thousand dinars.”

Weights and Measures

For weights and measures, Al-Muqaddasi shows the same attention to specific detail. For each province, he names, measures, compares and explains the fluctuations and variations in each measure and weight. . He would also dwell on the history of each; and so minute it all becomes in the detail, that it ends like the finance page of a broadsheet newspaper, with values, stocks and shares exhibited in all their minute variations, so tedious for the general reader, so fascinating to the expert.

Naval Transport:

During his visit to the bustling port of Old Cairo, al Muqaddasi narrates:

Urban Development

The Islamic urban setting, its evolution, diversity, complexity, economy and politics is what attracts most of the attention of Al-Muqaddasi. It re-occurs in each chapter, for every region and place he visits. A. Miquel offers an excellent summary of Al-Muqaddasi’s interest in the subject but in French.[118] Al-Muqaddasi differentiates between town and city by the presence of the great mosque, and its minbar, symbols of Islamic authority. In connection with this, he adds:

Al-Muqaddasi focuses most particularly on the defensive structures of every city. Walls, their height, thickness, distances between each, fortifications, access in and out, their location according to the general topography, and in relation to the rest, artificial obstacles, in particular, attract his attention. And so do daily concerns such as trade and exchanges, markets and the urban economy as a whole.

Al-Muqaddasi studies markets, their expansion and decline, providing also a bill of health for each, the revenues derived from them, both daily and monthly, and how such revenues are distributed.[120] He also studies carefully how a location is run, and its citizens act, dwelling particularly on such factors as order, cleanliness, morality and state of learning, all of which he considers for each and every place visited.

Considering the links between topography and urban expansion, he notes that in places such as Arabia, it is the sea alone that explains the presence of towns and people, opening up frontiers beyond the sea itself for trade and exchange.[121] Thus on Adan, in the Yemen, he notes:

The impact of space and climate on physical features are well observed, too, the author noting that colder places, such as Ferghana and Khwarizm, thicken beards and increase amounts of fat in bodies. Local customs form a major point of his interest; Al-Muqaddasi narrates one from Pre-Islamic and Newly Islamised Egypt which is of particular interest:

Diets, clothing, dialects, differences of all sorts, form other elements of study for the many ethnic groups of the vast Muslim lands. A diversity in union, which Miquel notes in his conclusion, was to be completely shattered by the Mongol irruption.