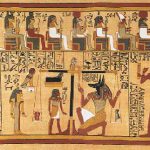

There was another power in Egypt which had been growing long before Amenhotep III came to the throne: the cult of Amun. Land ownership meant wealth in Egypt and, by Amenhotep III’s time, the priests of Amun owned almost as much land as the king. In accordance with traditional religious practice, Amenhotep III did nothing to interfere with the work of the priests, but it is thought that their immense wealth, and threat to the power of the throne, had a profound effect on his son. The god Aten was only one of many gods worshipped in ancient Egypt but, for the royal family, he had a special significance which would later become manifest in the religious edicts of Akhenaten. At this time, however, the god was simply another worshipped alongside the rest.

Perhaps in an attempt to wrest some power from the priests of Amun, Amenhotep III identified himself with Aten more directly than any pharaoh had previously. Aten was a minor sun god, but Amenhotep III elevated him to the level of a personal deity of pharaoh. Hawass writes:

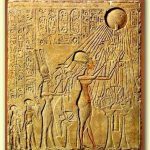

The sun god was a complex creature, whose dogma had been developing for thousands of years. In addition to his main incarnation as Re, this god was associated with the creator Atum as well as with deities such as Khepri…and Osiris, with whom Re merged at night. Another aspect of this god was the Aten; according to texts dating back at least to the Middle Kingdom, this was the disk of the sun, with which the king merged at death. This divine aspect, unusual in that it was not anthropomorphic, was chosen by Amenhotep III as a primary focus of his incarnation. It has been suggested that the rise of the Aten was linked specifically with maintenance of the empire, as the area over which, at least theoretically, the sun ruled. By associating himself with the visible disk of the sun, the king put himself symbolically over all the lands where it could be seen – all the known world, in fact (31).

Amenhotep III’s elevation of Aten as his personal god was not uncommon. Pharaohs in the past were associated with a particular cult of a favored god and, obviously, Amenhotep III did not neglect the other gods in preference to Aten. If his goal in raising awareness of Aten was politically motivated, it did not accomplish very much at all during his reign. The cult of Amun continued to grow and amass wealth and, in doing so, continued to pose a threat to the royal family and the authority of the throne.

Amenhotep’s Death & the Reign of Akhenaten

Amenhotep III suffered from severe dental problems, arthritis, and possibly obesity in his final years. He wrote to Tushratta, the king of Mitanni (one of whose daughters, Tadukhepa, was among Amenhotep III’s lesser wives) to send him the statue of Ishtar that had visited Egypt before, at his wedding to Tadukhepa, to heal him. Whether the statue was sent is a matter of controversy in the modern day and what, precisely, was ailing Amenhotep the III is likewise. It has been suggested that his dental problems resulted in an abscess which killed him but this has been disputed.

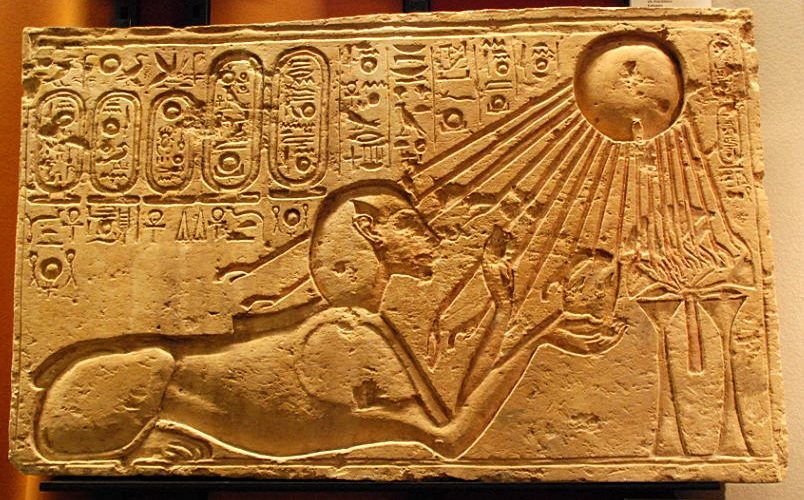

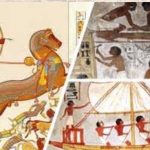

King Amenhotep III as a Lion

He died in 1353 BCE and letters from foreign rulers, such as Tushratta, express their grief on his passing and their condolences to Queen Tiye. These letters also make clear that these monarchs hoped to continue the same good relations with Egypt under the new king as they had with Amenhotep III. With Amenhotep III’s passing, his son, then called Amenhotep IV, began his reign. At first, there was nothing which distinguished Amenhotep IV’s rule from that of his father; temples were raised and monuments built just as before. In the fifth year of his reign, however, the new pharaoh underwent a religious conversion and outlawed the ancient religion of Egypt, closed the temples, and proscribed all religious practice. In place of the old faith, the king instituted a new one: Atenism. He changed his name to Akhenaten and created the first state mandated monotheistic system in the world.

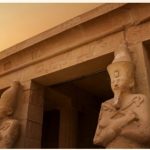

Akhenaten continued to build monuments and temples just as his father had, but “these temples were not to Amun, but to the sun disk as the Aten” (Hawass, 36). The Aten was now the one true god of the universe and Akhenaten was the living embodiment of this god. The new king abandoned the palace at Thebes and built a new city, Akhetaten (`the horizon of Aten’) on virgin land in the middle of Egypt. From his new palace he issued his royal decrees but seems to have spent most of his time on his religious reforms and neglected the affairs of state and, especially, foreign affairs. Vassal states, such as Byblos, were lost to Egypt, and the hopes which foreign rulers had expressed in continuing good relations with Egypt were disappointed.

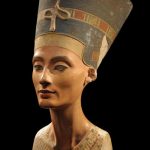

Akhenaten’s wife, Queen Nefertiti, assumed the responsibilities of her husband and, though she was adept at this, his neglect of his duties had already resulted in enormous loss of Egypt’s wealth and prestige. During Akhenaten’s reign, the treasury was slowly depleted, military discipline and efficacy was lax, and the people of Egypt, deprived of their traditional religious beliefs and the financial benefits associated with religious practices, suffered. Those who had once sold statuary or amulets or charms outside of temples no longer had a job, as the selling of such objects was illegal and those who worked in, or for, those temples were also unemployed. Foreign affairs were neglected as completely as the domestic and, by the time of Akhenaten’s death in 1336 BCE, Egypt had fallen far from its height under the reign of Amenhotep III.

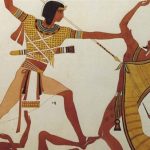

Akhenaten’s son and successor, Tutankhamun, tried to reverse the fortunes of his country in the brief ten years of his reign but died at the age of 18 before he could accomplish his goals. He did, however, overturn his father’s religious reforms, open the temples, and re-establish the old religion. His successor, Ay, continued these policies, but it would be Ay’s successor, Horemheb, who would completely erase, or try to, the damage done to the country by Akhenaten’s policies. Horemheb destroyed the city of Akhetaten, tore down the temples and monuments to Aten, and did this so thoroughly that later generations of Egyptians believed that he was the successor to Amenhotep III. Horemheb restored Egypt to the prosperity it had enjoyed before Akhenaten’s reign, but Egypt never was able to manage the heights it had enjoyed under Amenhotep III, the luxurious pharaoh, diplomat, hunter, warrior, and great architect of Egyptian monuments.