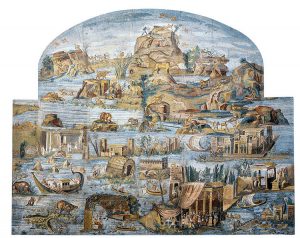

Ptolemaic Egypt rapidly established itself as an economic powerhouse of the ancient world at the end of the 4th century BCE. The wealth of Egypt was owed in large part to the unrivalled fertility of the Nile, which served as the breadbasket of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Egypt’s economy underwent numerous radical changes during the Ptolemaic period, including the introduction of Egypt’s first official coinage, the cultivation of new crops, and the growth of international trade. Corrupt bureaucratic practices, droughts, military expenditures, and political unrest plagued the economy of the Ptolemaic dynasty as the kingdom went into a period of decline in the 2nd century BCE. Nevertheless, Ptolemaic Egypt remained one of the largest economies in the Mediterranean until the Romanconquest of Egypt in 30 BCE.

Managing the Egyptian economy

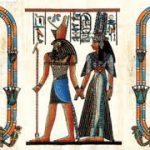

Instead of uprooting Egyptian tradition, the Ptolemaic dynasty incorporated pre-existing administrative practices when they assumed control of Egypt in the late 4th century BCE. Ptolemy II Philadelphus (c. 285 BCE – 246 BCE) laid the foundation of Ptolemaic economic policies by introducing new revenue and property laws and new taxes. Ptolemy II also began the distribution of ‘instruction texts’ describing ideal governmental behaviour to officials as an attempt to create some kind of bureaucratic standard.

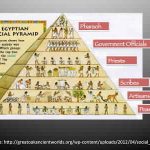

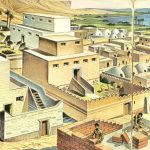

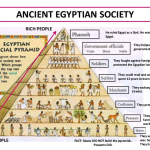

The chief economic minister in Ptolemaic Egypt was the dioiketes, who was appointed by the ruling monarch to set Egypt’s economic policies. All of the offices dealing with finances, agriculture, and record-keeping were under his auspices. As a matter of practicality, ancient Egypt was divided into administrative provinces known as nomes. At the nome level, officials dealt with municipal and village authorities to handle economic issues like land management, taxation, and the circulation of currency.

On the surface, Ptolemaic Egypt appears to be a highly organised bureaucracy, which early modern historians characterised as the product of a highly centralised despotic state. The Ptolemaic crown may have directed economic policies but these could only be enforced by local authorities who sought to increase their own power and prestige. To complicate the issue, the Ptolemaic government lacked a clear chain of command, and areas of responsibility frequently overlapped. The independent initiative of farmers and merchants should also not be discounted. The economy of Ptolemaic Egypt was therefore never the product of state-direction, but the result of overlapping fiscal, agricultural, and social influences. Sitta Von Reden in The Ancient Economy and Ptolemaic Egypt concisely summed this up

The transformation of a system into one based on coinage and contract, however, was not achieved by force or centralisation as previous scholars have argued; rather, it was a system carefully devised as a balance of state and local power, royal patronage and private initiative, as well as indigenous agrarian patterns and Greekinnovation.

Corruption plagued all levels of government and gave way to predatory bureaucratic practices. This condition persisted in spite of royal decrees forbidding the financial exploitation of Ptolemaic subjects by officials. As a result of the broken fiscal system, Ptolemaic rulers frequently began their reigns by providing blanket forgiveness on all debts owed to the government to help undo past damage from state corruption.

From the 3rd century BCE onwards, social and economic inequality caused uprisings and civil unrest, which further strained the Egyptian economy. The largest uprising occurred between 205 BCE and 185 BCE when Upper Egypt temporarily seceded from the Ptolemaic Kingdom with Nubian support. Upper Egypt was reconquered during the reign of Ptolemy V (204 BCE – c. 180 BCE), but the effects of this insurrection rocked Egypt and prompted the Ptolemaic dynasty to reform many aspects of its rule.

Landowners & Labourers

An estimated 30-50% of farmland in Ptolemaic Egypt was owned directly by the crown, with temple property making up another large category of land. Temples managed land, archived information, and owned large estates which supported temple expenses through agricultural output and taxation. Contrary to popular belief, private landowning did exist in Ptolemaic Egypt and is especially well attested in Upper Egypt.

The Ptolemaic dynasty granted allotments of arable land to cavalry and infantrymen for their lifetime in order to create a loyal landowning class of soldiers (referred to as cleruchs) comparable to that of Greece and Macedon. Cleruchs were predominantly Greeks, Thracians, Cyrenians, and Hellenized Egyptians whose sons inherited their status and received ‘gift-estates’ of their own upon entering military service. Officials and favourites of the royal family were also given estates.

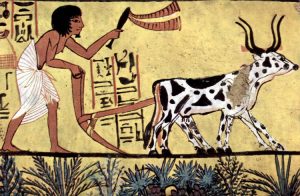

As elsewhere in the ancient Mediterranean, the majority of the Egyptian population were agricultural labourers. Most were tenant farmers who lived and worked on rented or leased plots of land. Tenant farmers were provided with farming equipment by their employers and loaned seed. Wage labour was also quite frequently used by both the crown and estate holders. Ptolemaic subjects were summoned by the crown for labour levies at certain times of year when extra manpower was needed to assist in the plantings and harvests.

Agriculture

In the Ptolemaic period, Egypt was a major producer of grain, wine, flax, cotton, papyrus, and a wide range of fruits, vegetables, and spices. The introduction of new crops, the cultivation of wine and olive oil during the Ptolemaic period played an important role in the transformation of Egyptian food and culture at this time. The earliest investors in this agricultural revolution were cleruchic soldiers or Ptolemaic officials like Apollonius, the dioiketes of Ptolemy II. Olives and grapes gradually became staple crops as the traditional diet became increasingly influenced by Mediterranean cuisine in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt. Wine had been cultivated in Egypt for millennia but the consumption of wine in Egypt was nowhere near as ubiquitous or culturally significant as it was in Greece. The climate in most of Egypt did not lend itself to winemaking and Egyptian wine was notoriously poor. To help improve vintages, some vineyard owners imported older vines from Greece at high costs to cultivate in Egypt.

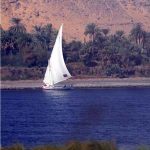

During the Ptolemaic period, Egyptian farmers began to cultivate durum wheat in place of the emmer wheat and barley. These new grains fetched higher prices on foreign markets and were more popular with Hellenistic and Near Eastern settlers in Egypt. The downside was that these new crops required even more water than the traditional Egyptian staples they replaced. In the late 3rd century BCE, large systems of canals were constructed to irrigate land that was otherwise too far from the Nile to be fed by the river. These canals were maintained through a combination of contracted wage labour and labour levies.

New irrigation techniques also played a role in opening up more land for agricultural use. At this time, a massive land reclamation program was launched to drain the marshy Fayum, which would become an important agricultural zone in Ptolemaic Egypt. The reliance on the Nile’s annual flooding, rather than rain, was both a gift and a weakness of Egypt. The Nile’s failure to fully flood in certain years led to periodic droughts and famines. To cope with these recurring famines, government stockpiles of grain and lentils might be sold on the market or distributed to the people.