Each home had its own altar which had to be kept clean and neat. People did not go to the temples in town to worship their gods but held private ceremonies and rituals in their houses. These altars would usually have an image or statue of a patron god or goddess and offerings would be placed there along with prayers making requests or giving thanks. This practice was especially prevalent in the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-1069 BCE) and seems to have given rise to rituals which modern-day scholars refer to as the Domestic Cult or cults of domesticity.

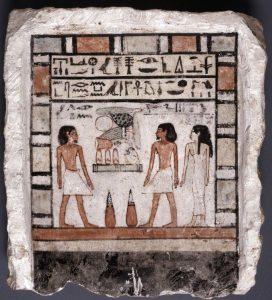

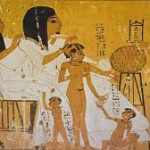

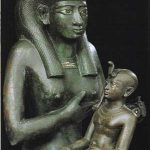

These cults are suggested by archaeological discoveries and inscriptions which seem to indicate an elevated focus on appreciation of the feminine by focusing on female deities. Pretty much every home is assumed to have had a personal altar honoring the family’s protective deities and ancestors, but these altars predominantly feature statuettes, images, and amulets of Renenutet (a goddess of protection in cobra form), Taweret (protective goddess of childbirth and fertility in hippo form), Bes (protective god of childbirth, children, fertility, and sexuality), and Bastet (goddess of women, children, hearth, home, and women’s secrets). Scholar Barry J. Kemp notes how, in the worker’s village at Deir el-Medina, there are paintings on the walls of the upstairs rooms which “supplied the focus for domestic feminity” (305). This cult is thought to have developed in response to the essential role women played in the daily life of the home.

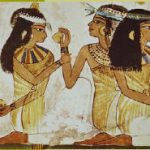

Egyptologist Gay Robins notes how “the rites practiced in the domestic cult may have included offering food, libations, and flowers at the altar, as in other Egyptian cults” and that these rituals “suggest that women of the family had an important part to play” (163). While this is no doubt true, and there may well have been a “domestic cult,” it is also possible that home altars during the New Kingdom simply celebrated the feminine aspect of divinity and protection more often than the masculine or that these kinds of altars have been found intact more than others.

It must be kept in mind that goddesses feature more prominently in Egyptian religious beliefs and stories than in those of other cultures and so it is hardly surprising to find home altars honoring the feminine. Bastet was not just a “woman’s goddess” but one of the most popular deities in all of Egypt with both sexes, and the Cult of Isis became so popular that it would outlast every other Egyptian cult hundreds of years into the Christian era. The festivals of goddesses like Bastet, Isis, Hathor, and Neith were national events in which everyone participated just as they did for gods like Osiris, Ptah, and Amun.