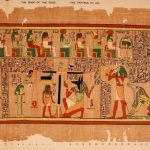

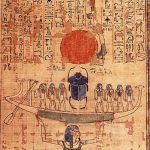

Egyptian culture incorporated this concept of immortality quite nicely into their religious system through the Osiris myth. In fact, a minority of historians believe that Osiris was an actual real human being at one time in Egyptian history—perhaps an ancient ruler who experienced a civil war during his reign, and who received glory and deification post–mortem as the ancients often did for heroes of old. Regardless, the Osiris myth proposed that through the supernatural powers of Horus and the clever vengeful machinations of Osiris’ wife, Isis, Osiris became a god and was reborn each year during the Nile’s annual flood as Pharaoh of the land. His son, Horus, and his wife, Isis, would also be reincarnated in a continual cycle that guaranteed the royal divine lineage would never cease.

This story was not only empowering to the aristocracy in Egypt but also to all people in Egypt, according to Hamilton–Paterson and Andrews who write that with the great “power” of this myth, “The ordinary Egyptian could easily identify with him [Osiris]” (23). In a severe hierarchical society, it allowed the Egyptian peasant an opportunity to enjoy the good life beyond death, as with the Pharaoh; and joined them together in a divine, eternal religious practice. Evidence of this grand embrace of mummification can be found in such archaeological discoveries as the Valley of the Golden Mummies at the Bahariya Oasis, southwest of modern–day Cairo.

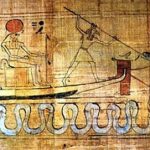

Budge gives a clear description of the purposes behind mummification. He states that mummification was used so that the Egyptian’s

soul [Ba], and his intelligence [Ka], when they returned some thousands of years hence to seek out the body in the tomb, might enter into the body once more, and revivify it, and live with it forever in the Kingdom of Osiris.

To aid in this goal, carefully drawn out funeral rites were carried out to protect and secure the Ka for future life. The Ba was what the mummified body was called after it joined with the Ka. In the Ba, the Egyptian could “take on any shape he chose when leaving his tomb” (Hamilton–Paterson & Andrews, 18). Additionally, the Egyptian Akh was that portion of him which “dwelt among the stars rather than in an afterworld” (Hamilton–Paterson & Andrews, 20). He could, therefore, share immortality with Osiris, although he may not ever be equal to him.

Beliefs & Afterlife

As referred to earlier, in this process of death and reincarnation involving the Ba and the Ka, a contradiction occurs. Is the dead Egyptian’s spirit in the tomb (or wherever the body was placed) or circling around the heavens? The question was unanswered in Egyptian theology. Nevertheless, Egyptians seem to have managed to set aside mutually conflicting ideas of immortality and allow for divine dissonance and limited understanding of the afterlife; however, events such as the dramatic shift to psuedo–monotheism of Akhenaten in the 14th century BCE suggest that Egyptian religious life was not set in stone, ironically.

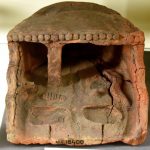

One of the problems in understanding the religious concepts surrounding death and mummification is the impossibility of knowing how widespread and dogmatic these beliefs were in the whole of Egyptian society. Unfortunately, nearly all ancient Egyptian records are from the rich, royalty, or the priesthood. As Hamilton–Paterson and Andrews state, “So much is known about the upper–class ancient Egyptians’ lives and culture that there is no longer any room for transcendental speculations” (20); however, the same is not true regarding the beliefs of the peasants in lower Egyptian society. The prevalence of magic and cults (as seen in the multitudinous references in tombs and burial sites) also include references to unheard–of, obscure deities and mystery religions, which suggests that not all Egyptians went along with the Osiris myth theological presumptions.

Still, one can still perceive a common thread in nearly all ancient funeral practices from the Old Kingdom to the New, despite any superfluous differences. Archaeologists and historians have been (and still are) astounded and impressed at the care and delicacy given to the deceased during the mummification process. No doubt, this meticulous and methodical treatment arose in ancient Egypt from a cultural sense of unity and hope in the afterlife, wherein decomposition just “upset so much theology”.