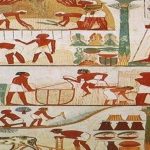

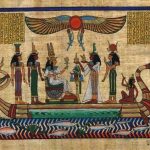

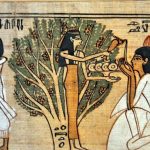

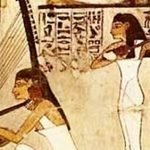

The paintings on Meket-Ra’s walls would have been done by artists mixing colors made from naturally occurring minerals. Black was made from carbon, red and yellow from iron oxides, blue and green from azurite and malachite, white from gypsum and so on. The minerals would be mixed with crushed organic material to different consistencies and then further mixed with an unknown substance (possibly egg whites) to make it sticky so it would adhere to a surface. Egyptian paint was so durable that many works, even those not protected in tombs, have remained vibrant after over 4,000 years.

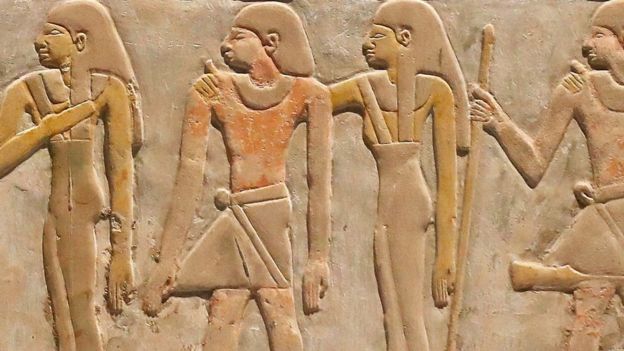

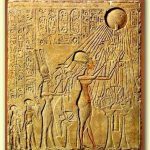

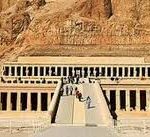

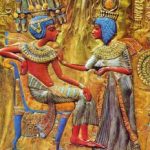

Although home, garden, and palace walls were usually decorated with flat two-dimensional paintings, tomb, temple, and monument walls employed reliefs. There were high reliefs (in which the figures stand out from the wall) and low reliefs (where the images are carved into the wall). To create these, the surface of the wall would be smoothed with plaster which was then sanded. An artist would create a work in minature and then draw gridlines on it and this grid would then be drawn on the wall. Using the smaller work as a model, the artist would be able to replicate the image in the correct proportions on the wall. The scene would first be drawn and then outlined in red paint. Corrections to the work would be noted, possibly by another artist or supervisor, in black paint and once these were taken care of the scene was carved and painted.

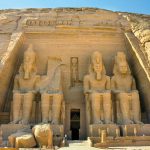

Paint was also used on statues which were made of wood, stone, or metal. Stone work first developed in the Early Dynastic Period and became more and more refined over the centuries. A sculptor would work from a single block of stone with a copper chisel, wooden mallet, and finer tools for details. The statue would then be smoothed with a rubbing cloth. The stone for a statue was selected, as with everything else in Egyptian art, to tell its own story. A statue of Osiris, for example, would be made of black schist to symbolize fertility and re-birth, both associated with this particular god.

Metal statues were usually small and made of copper, bronze, silver, and gold. Gold was particularly popular for amulets and shrine figures of the gods since it was believed that the gods had golden skin. These figures were made by casting or sheet metal work over wood. Wooden statues were carved from different pieces of trees and then glued or pegged together. Statues of wood are rare but a number have been preserved and show tremendous skill.

Cosmetic chests, coffins, model boats, and toys were made in this same way. Jewelry was commonly fashioned using the technique known as cloisonne in which thin strips of metal are inlaid on the surface of the work and then fired in a kiln to forge them together and create compartments which are then detailed with jewels or painted scenes. Among the best examples of cloisonne jewelry is the Middle Kingdom pendant given by Senusret II (c.1897-1878 BCE) to his daughter. This work is fashioned of thin gold wires attached to a solid gold backing inlaid with 372 semi-precious stones. Cloisonne was also used in making pectorals for the king, crowns, headdresses, swords, ceremonial daggers, and sarcophagi among other items.

Conclusion

Although Egyptian art is famously admired it has come under criticism for being unrefined. Critics claim that the Egyptians never seem to have mastered perspective as there is no interplay of light and shadow in the compositions, they are always two dimensional, and the figures are emotionless. Statuary depicting couples, it is argued, show no emotion in the faces and the same holds true for battle scenes or statues of a king or queen.

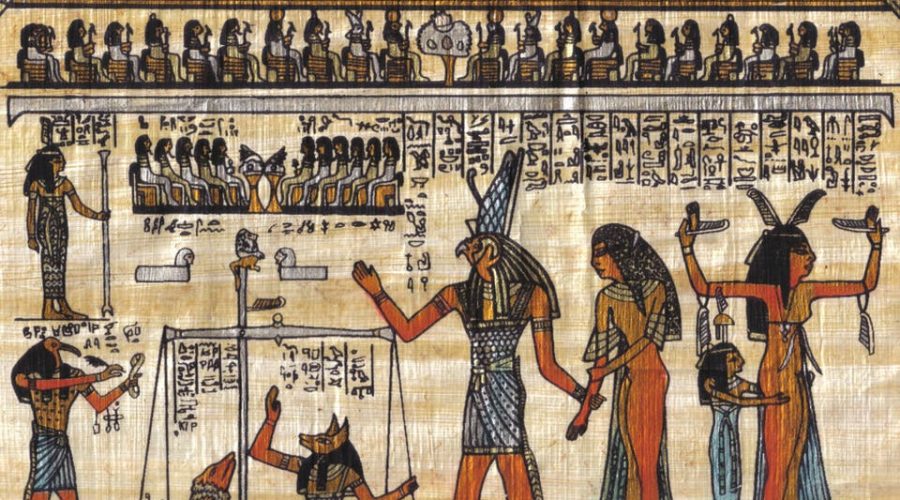

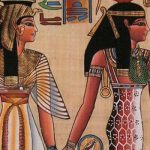

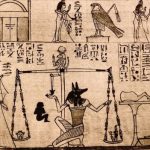

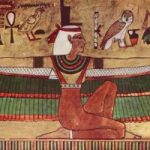

These criticisms fail to recognize the functionality of Egyptian art. The Egyptians understood that emotional states are transitory; one is not consistently happy, sad, angry, content throughout a given day much less eternally. Art works present people and deities formally without expression because it was thought the person’s spirit would need that representation in order to live on in the afterlife. A person’s name and image had to survive in some form on earth in order for the soul to continue its journey. This was the reason for mummification and the elaborate funerary rituals: the spirit needed a ‘beacon’ of sorts to return to when visiting earth for sustenance in the tomb.

The spirit might not recognize a statue of an angry or jubilant version of themselves but would recognize their staid, complacent, features. The lack of emotion has to do with the eternal purpose of the work. Statues were made to be viewed from the front, usually with their backs against a wall, so that the soul would recognize their former selves easily and this was also true of gods and goddesses who were thought to live in their statues.

Life was only a small part of an eternal journey to the ancient Egyptians and their art reflects this belief. A statue or a cosmetics case, a wall painting or amulet, whatever form the artwork took, it was made to last far beyond its owner’s life and, more importantly, tell that person’s story as well as reflecting Egyptian values and beliefs as a whole. Egyptian art has served this purpose well as it has continued to tell its tale now for thousands of years.