The Nile River was the source of life for the ancient Egyptians and so figured prominently in their religious beliefs. At night, the Milky Way was considered a heavenly Nile, associated with Hathor, and provider of all good things. The Nile was also linked to Uat-Ur, the Egyptian name for the Mediterranean Sea, which stretched out to unknown lands from the Delta and brought goods through trade with foreign ports.

Watercrafts were no doubt among the earliest conveyances built in Egypt, with small boats appearing in inscriptions in the Predynastic Period (c. 6000 – c. 3150 BCE). These boats were made of woven papyrus reeds but later were made of wood, grew larger, and became ships.

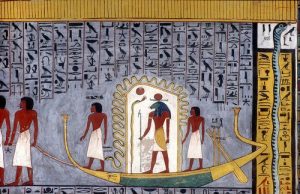

The ships of the Egyptians were used for commercial ventures like fishing, trade, and travel and also in warfare, but from at least the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE), they also feature in religious beliefs and practices. Ships known as Barques of the Gods are associated with a number of different Egyptian deities and, although each had its own significance, their common importance was in linking the mortal world with the divine.

The Barque of Ra

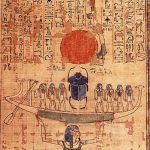

Easily the most important divine vessel was the Barque of Ra which sailed across the sky each day as the sun. In one religious tale, Ra becomes enraged with humanity and their ceaseless stupidity and decides to destroy them by sending Sekhmet to devour them and crush their cities. He repents and stops her by sending her a vat of beer, which she drinks, passes out from, and wakes up later as Hathor, the friend to humans. In some versions, the story ends there, but in others, Ra is still not satisfied with humanity and so boards his great barge and sails away into the heavens. Still, since he cannot completely distance himself from the world, he appears each day watching over it as the sun. The solar barque the people saw during the day was called the Mandjet, and the one which navigated through the underworld was known as the Meseket.

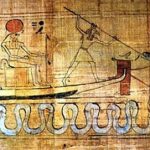

By the time of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE), this myth included the added dimension of the Great Serpent known as Apophis. As the Barque of Ra descended into the west in the evening, it entered the underworld where Apophis waited to attack it. Apophis was present at the beginning of creation when, in one myth, Ra is the god who stands on the primordial mound and raises order out of chaos. Apophis wanted to return the universe to its original undifferentiated state and could do this if he destroyed the barge of the sun god and the sun god with it.

Other gods, as well as the souls of the justified dead, would travel on the barge with Ra to protect him and his ship from Apophis during its journey through the underworld. A number of paintings and inscriptions depict all of the most famous gods, at one time or another, fending off the Great Serpent either alone, in groups, or in the presence of the justified dead.

Mortals were encouraged to participate in this struggle from their homes and temples on earth. Rituals such as The Overthrowing of Apophis were observed in which figures and images of Apophis were made of wax and then ritually mutilated, spat on, urinated on, and burned. This was among the most widely practiced execration rituals in Egypt and linked the living with the souls of those who had passed on and with the gods.

Every night the gods, souls, and humanity joined together to battle chaos and darkness and preserve life and light, and each time they won, the sun rose in the morning, and the dawn light was an assurance that all was well with Ra and life on earth would continue. As the barge sailed across the sky, however, Apophis returned to life in the underworld and would be waiting again once night fell; and so the battle would have to be fought again.

The Barque of Amun

Ra’s barge existed in the spiritual realm but there were others which were built and maintained by human hands. The best known of these was the Barque of Amun constructed and kept at Thebes.

Amun’s Barque was known to the Egyptians as Userhetamon, ‘Mighty of Brow is Amun,’ and was a gift to the city from Ahmose I (c. 1570 – c.1544 BCE) following his victory over the Hyksos and ascension to the throne which initiated the era of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-1069 BCE). Egyptologist Margaret Bunson writes, “It was covered in gold from the waterline up and was filled with cabins, obelisks, niches, and elaborate adornments” (21). There was a cabin for the shrine of the god, decorated with gold, silver, and precious gems, from which Amun, in the form of his statue, would preside over festivals and welcome the praise of his people.

During Amun’s annual festival, The Feast of Opet, the barque would move with great ceremony, carrying Amun’s statue from the Karnak temple downriver to the Luxor temple so the god could visit and then bringing him back again. At the ritual of the Wadi Festival (The Beautiful Feast of the Valley), one of the most significant of all Egyptian festivals, the statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu (the Theban triad) were transported on the barque from one side of the Nile to the other in order to participate in honoring the deceased and inviting their spirits back to earth to join in the festivities.

On other days the barque would be docked on the banks of the Nile or at Karnak’s sacred lake. When not in use, the ship would be housed in a special temple at Thebes built to its specifications, and every year the floating temple would be refurbished and repainted or rebuilt. Other barques of Amun were built elsewhere in Egypt, and there were other floating temples to other deities, but Amun’s Barque at Thebes was the most elaborate. The attention lavished on the ship reflected the status of the god who, by the time of the New Kingdom, was so widely venerated that his worship was almost monotheistic with other gods relegated nearly to the status of aspects of Amun.

The Barque of Osiris

Among his closest competitors for first place in the hearts of the people, however, was Osiris. Osiris was considered the first king of Egypt who, murdered by his brother Set and revived by his sister-wife Isis and her sister Nephthys, was the Lord and Judge of the Dead. Osiris’ son Horus was among the most important deities of the pantheon, associated with the just reign of the king and, in most eras, identified with the king himself.

When a person died, they expected to have to appear before Osiris for judgment concerning their deeds in life. Although the judgment of the soul would be influenced by the 42 Judges, Thoth, and Anubis who would participate in accepting or rejecting one’s Negative Confession and the weighing of the heart, it was Osiris’ word which would be final. Since one’s continued existence in the afterlife depended upon his mercy, he was perpetually venerated throughout Egypt’s history.

Worship of Osiris dates conclusively to the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE) but no doubt originated in the Predynastic Period. The story of his death and resurrection by Isis became so popular that it pervaded Egyptian culture and, even when other gods might be honored more elaborately in state ceremonies, the festival of Osiris remained significant and his cult widespread. Mortuary rituals were based on the Osiris cult and the king was linked to Horus in life and Osiris in death. The king was, in fact, thought to travel to the land of the dead in his own barge which resembled the ship of Osiris.

Osiris’ barque was known as the Neshmet Barge which, though built by human hands, belonged to the primordial god Nun of the waters. Bunson writes, “An elaborate vessel, this bark had a cabin for the shrine and was decorated with gold and other precious metals and stones…it was refurbished or replaced by each king” (43). The Neshmet barge was considered so important that participation in its replacement or restoration was counted as one of the most significant good deeds in one’s life.

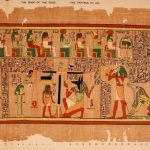

During the Festival of Osiris at Abydos, the Neshmet would transport Osiris’ statue from his temple to his tomb and back again, thus recreating the story of his life, death, and resurrection. At the beginning of the festival, two maidens of the temple would play the roles of the goddesses in reciting the call-and-response liturgy of The Lamentation of Isis and Nephthys which invited Osiris to participate in the ceremony while also ritually recreating his resurrection. Once he emerged from his temple in the form of his statue, the Neshmet Barge was waiting to transport him and the ceremony would be underway.

Ships of the Gods, King, & of the People

Many other gods and goddesses had their own ships which were all built along the same lines as the above. All were elaborately adorned and outfitted as floating temples. Bunson describes the barques of some of the other gods:

Other Egyptian deities sailed in their own barks on feast days with priests rowing the vessels on sacred lakes or on the Nile. Khons’ Bark was called “Brilliant of Brow” in some eras. The god Min’s boat was named “Great of Love”. The Hennu Bark of Sokar was kept at Medinet Habu and was paraded around the walls of the capital on holy days. This bark was highly ornamented and esteemed as a cultic object. The barks could be actual sailing vessels or carried on poles in festivals. The gods normally had both kinds of barks for different rituals.

Hathor’s barque at Dendera was of similar opulence and the temples of major deities had a sacred lake on which the ship could sail during feast days or on special occasions. This association of the gods with watercraft led to the belief that the king departed his earthly life for the next world in a similar boat. Prayers and hymns for the deceased monarch include the hope that his ship will reach the afterlife without mishap and some spells indicate navigational instructions. For this reason, boats were often included among the grave goods of the deceased.

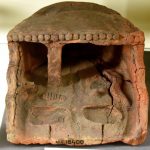

The best known of these is the Ship of Khufu, but so-called Solar Barges were buried with many kings throughout Egypt’s history. Khufu (2589-2566 BCE), the builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza, had his barge buried near his tomb for use in the afterlife, as with any of his other grave goods. He was neither the first to do so nor, by far, the last and it became customary to include even a model boat among the grave goods in the tombs of the upper class.

These full-sized or model boats were thought, like all grave goods, to serve the soul of the deceased in the afterlife. Even a model ship could be used to transport one safely from a certain point to another through the use of magical spells. Statuettes of various animals, like the hippopotamus, were often included in tombs for this same purpose: they would come to life when summoned by a spell to help the soul when required.

The ships, large or small, provided the same service and, by including them in one’s tomb, one was assured of easy travel in the realm of the gods. More importantly, though, one’s personal boat linked the soul with the divine in the same way the ships of the gods had done when one lived on the earth.