Ancient Egyptian art includes painting, sculpture, architecture, and other forms of art, such as drawings on papyrus, created between 3000 BCE and 100 AD. Most of this art was highly stylized and symbolic. Many of the surviving forms come from tombs and monuments, and thus have a focus on life after death and preservation of knowledge.

Symbolism

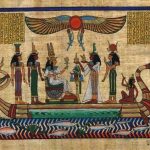

Symbolism in ancient Egyptian art conveyed a sense of order and the influence of natural elements. The regalia of the pharaoh symbolized his or her power to rule and maintain the order of the universe. Blue and gold indicated divinity because they were rare and were associated with precious materials, while black expressed the fertility of the Nile River.

Hierarchical Scale

In Egyptian art, the size of a figure indicates its relative importance. This meant gods or the pharaoh were usually bigger than other figures, followed by figures of high officials or the tomb owner; the smallest figures were servants, entertainers, animals, trees and architectural details.

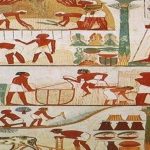

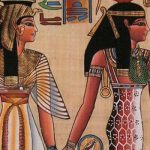

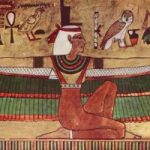

Painting

Before painting a stone surface, it was whitewashed and sometimes covered with mud plaster. Pigments were made of mineral and able to stand up to strong sunlight with minimal fade. The binding medium is unknown; the paint was applied to dried plaster in the “fresco a secco” style. A varnish or resin was then applied as a protective coating, which, along with the dry climate of Egypt, protected the painting very well. The purpose of tomb paintings was to create a pleasant afterlife for the dead person, with themes such as journeying through the afterworld, or deities providing protection. The side view of the person or animal was generally shown, and paintings were often done in red, blue, green, gold, black and yellow.

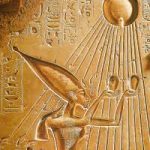

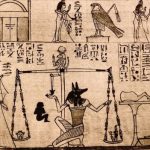

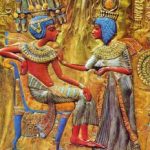

Sculpture

Ancient Egyptians created both monumental and smaller sculptures, using the technique of sunk relief. In this technique, the image is made by cutting the relief sculpture into a flat surface, set within a sunken area shaped around the image. In strong sunlight, this technique is very visible, emphasizing the outlines and forms by shadow. Figures are shown with the torso facing front, the head in side view, and the legs parted, with males sometimes darker than females. Large statues of deities (other than the pharaoh) were not common, although deities were often shown in paintings and reliefs.

Colossal sculpture on the scale of the Great Sphinx of Giza was not repeated, but smaller sphinxes and animals were found in temple complexes. The most sacred cult image of a temple’s god was supposedly held in the naos in small boats, carved out of precious metal, but none have survived.

Ka statues, which were meant to provide a resting place for the ka part of the soul, were present in tombs as of Dynasty IV (2680-2565 BCE). These were often made of wood, and were called reserve heads, which were plain, hairless and naturalistic. Early tombs had small models of slaves, animals, buildings, and objects to provide life for the deceased in the afterworld. Later, ushabti figures were present as funerary figures to act as servants for the deceased, should he or she be called upon to do manual labor in the afterlife.

Many small carved objects have been discovered, from toys to utensils, and alabaster was used for the more expensive objects. In creating any statuary, strict conventions, accompanied by a rating system, were followed. This resulted in a rather timeless quality, as few changes were instituted over thousands of years.

Faience, Pottery, And Glass

Faience was sintered-quartz ceramic with surface vitrification used to create relatively cheap, small objects in many colors, but most commonly blue-green. It was often used for jewelry, scarabs, and figurines. Glass was originally a luxury item, but became more common, and was to used to make small jars, of perfume and other liquids, to be placed in tombs. Carvings of vases, amulets, and images of deities and animals were made of steatite. Pottery was sometimes covered with enamel, particularly in the color blue. In tombs, pottery was used to represent organs of the body removed during embalming, or to create cones, about ten inches tall, engraved with legends of the deceased.

Papyrus

Papyrus is very delicate and was used for writing and painting; it has only survived for long periods when buried in tombs. Every aspect of Egyptian life is found recorded on papyrus, from literary to administrative documents.

Architecture

Architects carefully planned buildings, aligning them with astronomically significant events, such as solstices and equinoxes, and used mainly sun-baked mud brick, limestone, sandstone, and granite. Stone was reserved for tombs and temples, while other buildings, such as palaces and fortresses, were made of bricks. Houses were made of mud from the Nile River that hardened in the sun. Many of these houses were destroyed in flooding or dismantled; examples of preserved structures include the village Deir al-Madinah and the fortress at Buhen.

The Giza Necropolis, built in the Fourth Dynasty, includes the Pyramid of Khufu (also known as the Great Pyramid or the Pyramid of Cheops), the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure, along with smaller “queen” pyramids and the Great Sphinx.

The Temple of Karnak was first built in the 16th century BCE. About 30 pharaohs contributed to the buildings, creating an extremely large and diverse complex. It includes the Precincts of Amon-Re, Montu and Mut, and the Temple of Amehotep IV (dismantled).

The Luxor Temple was constructed in the 14th century BCE by Amenhotep III in the ancient city of Thebes, now Luxor, with a major expansion by Ramesses II in the 13th century BCE. It includes the 79-foot high First Pylon, friezes, statues, and columns.

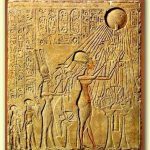

The Amarna Period (1353-1336 BCE)

During this period, which represents an interruption in ancient Egyptian art style, subjects were represented more realistically, and scenes included portrayals of affection among the royal family. There was a sense of movement in the images, with overlapping figures and large crowds. The style reflects Akhenaten’s move to monotheism, but it disappeared after his death.