The Romans controlled such a vast empire for so long a period that a summary of the art produced in that time can only be a brief and selective one. Perhaps, though, the greatest points of distinction for Roman art are its very diversity, the embracing of art trends past and present from every corner of the empire and the promotion of art to such an extent that it became more widely produced and more easily available than ever before. In which other ancient civilization would it have been possible for a former slave to have commissioned his portrait bust? Roman artists copied, imitated, and innovated to produce art on a grand scale, sometimes compromising quality but on other occasions far exceeding the craftsmanship of their predecessors. Any material was fair game to be turned into objects of art. Recording historical events without the clutter of symbolism and mythological metaphor became an obsession. Immortalising an individual private patron in art was a common artist’s commission. Painting aimed at faithfully capturing landscapes, townscapes, and the more trivial subjects of daily life. Realism became the ideal and the cultivation of a knowledge and appreciation of art itself became a worthy goal. These are the achievements of Roman art.

Art for All: Rome’s Contribution

Roman art has suffered something of a crisis in reputation ever since the rediscovery and appreciation of ancient Greek art from the 17th century CE onwards. When art critics also realised that many of the finest Roman pieces were in fact copies or at least inspired by earlier and often lost Greek originals, the appreciation of Roman art, which had flourished along with all things Roman in the medieval and Renaissance periods, began to diminish. Another problem with Roman art is the very definition of what it actually is. Unlike Greek art, the vast geography of the Roman empire resulted in very diverse approaches to art depending on location. Although Rome long remained the focal point, there were several important art-producing centres in their own right who followed their own particular trends and tastes, notably at Alexandria, Antioch, and Athens. As a consequence, some critics even argued there was no such thing as ‘Roman’ art.

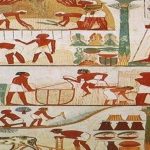

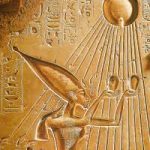

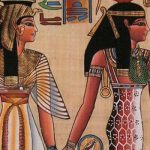

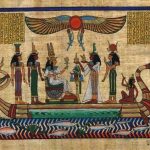

In more recent times a more balanced view of Roman art and a wider one provided by the successes of archaeology have ensured that the art of the Romans has been reassessed and its contribution to western art in general has been more greatly recognised. Even those holding the opinion that Classical Greek art was the zenith of artistic endeavour in the west or that the Romans merely fused the best of Greek and Etruscan art would have to admit that Roman art is nothing if not eclectic. Inheriting the Hellenistic world forged by Alexander the Great’s conquests, with an empire covering a hugely diverse spectrum of cultures and peoples, their own appreciation of the past, and clear ideas on the best way to commemorate events and people, the Romans produced art in a vast array of forms. Seal-cutting, jewellery, glassware, mosaics, pottery, frescoes, statues, monumental architecture, and even epigraphy and coins were all used to beautify the Roman world as well as convey meaning from military prowess to fashions in aesthetics.

Artworks were looted from conquered cities and brought back for the appreciation of the public, foreign artists were employed in Roman cities, schools of art were created across the empire, technical developments were made, and workshops sprang up everywhere. Such was the demand for artworks, production lines of standardised and mass produced objects filled the empire with art. And here is another factor in Rome’s favour, the sheer quantity of surviving artworks. Such sites as Pompeii, in particular, give a rare insight into how Roman artworks were used and combined to enrich the daily lives of citizens. Art itself became more personalised with a great increase in private patrons of the arts as opposed to state sponsors. This is seen in no clearer form than the creation of lifelike portraits of private individuals in paintings and sculpture. Like no other civilization before it, art became accessible not just to the wealthiest but also to the lower middle classes.