Last month, my colleagues and I published our analysis of an intact Egyptian prehistoric

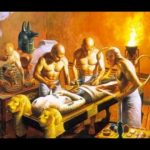

body, dating from around 3,700 to 3,500 BC, that had been housed in the Museo Egizio (Egyptian Museum) in Turin, Italy, since 1901. The results provide strong evidence that Egyptian mummification techniques — long associated with the time of the pharaohs — date back to 1,500 years earlier.

Before this, it was assumed that the dead man had been naturally mummified by the desiccating action of the hot, dry desert sand. But now we know he was deliberately preserved.

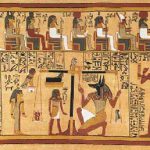

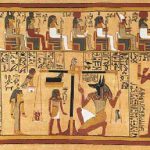

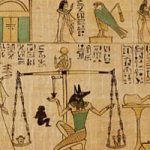

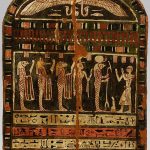

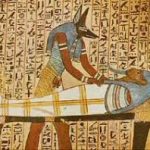

Together with our previous research, this new information tells us that the prehistoric Egyptians, living at the time the man died, already had knowledge of the processes required to preserve the body, and practiced a developed religious belief system about the afterlife.

We had hints

Prior to this new study, our analysis of funerary wrappings from prehistoric bodies found in sites in central Egypt proved that people who lived before the time of the pharaohs used some body preservation techniques.

Reports of pellets of resin, found in pouches with the bodies in early burials excavated at prehistoric sites at Badari and Mostagedda in Middle Egypt (circa 4,500 to 3,350 BC), had made me wonder whether they were already using resin in a rudimentary form of mummification.

Resin is a substance harvested from certain trees, particularly pine, and is a preservative component of embalming mixtures.

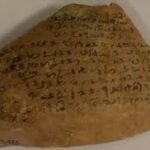

In our previous work we did not have whole bodies — only small fragments of linen conserved in British museums. These pieces of fabric — donated by excavators in the early 20th century in return for excavation funds — were the only surviving evidence the bodies had been wrapped.

Working with archaeological chemist Stephen Buckley, my colleague Ron Oldfield and I identified resin in the wrappings.

But we didn’t have any further samples to expand this work — until now.