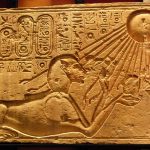

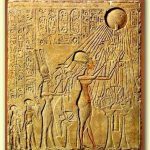

The pharaoh as a servant of the gods, and identified with a certain god (most often Horus), was common practice in ancient Egyptian culture, but no one before Akhenaten had proclaimed himself an actual god incarnate. As a god, he seems to have felt that the affairs of state were beneath him and simply stopped attending to his responsibilities. One of the many unfortunate results of Akhenaten’s religious reforms was the neglect of foreign policy.

From documents and letters of the time, it is known that other nations, formerly allies, wrote numerous times asking Egypt for help in various affairs and that most of these requests were ignored by the deified king. Egypt was a wealthy and prosperous nation at the time and had been steadily growing in power since before the reign of Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE). Hatshepsut and her successors, such as Tuthmosis III (1458-1425 BCE), employed a balanced approach of diplomacy and military action in dealing with foreign nations; Akhenaten chose simply to largely ignore what happened beyond the borders of Egypt and, it seems, most things outside of his palace at Akhetaten.

Watterson notes that Ribaddi (Rib-Hadda), king of Byblos, who was one of Egypt’s most loyal allies, sent over 50 letters to Akhenaten asking for help in fighting off Abdiashirta (also known as Aziru) of Amor (Amurru) but these all went unanswered and Byblos was lost to Egypt (112). Tushratta, the king of Mitanni, who had also been a close ally of Egypt, complained that Amenhotep III had sent him statues of gold while Akhenaten only sent gold-plated statues.

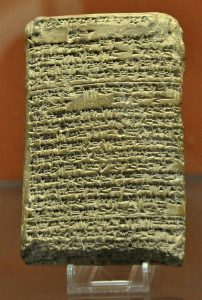

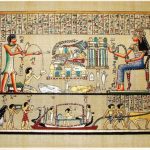

The Amarna Letters

The Amarna Letters, (correspondence found in the city of Amarna between the kings of Egypt and those of foreign nations) which provide evidence of Akhenaten’s negligence, also show him to have a keen sense of foreign policy when the situation interested him. He strongly rebuked Abdiashirta for his actions against Ribaddi and for his friendship with the Hittites who were then Egypt’s enemy. This no doubt had more to do with his desire to keep friendly the buffer states between Egypt and the Land of the Hatti (Canaan and Syria, for example, which were under Abdiashirta’s influence) than any sense of justice for the death of Ribaddi and the taking of Byblos.

There is no doubt that his attention to this problem served the interests of the state but, as other similar issues were ignored, it seems that he only chose those situations which interested him personally. Akhenaten had Abdiashirta brought to Egypt and imprisoned for a year until Hittite advances in the north compelled his release, but there seems a marked difference between his letters dealing with this situation and other king’s correspondence on similar matters.

While there are, then, examples of Akhenaten looking after state affairs, there are more which substantiate the claim of his disregard for anything other than his religious reforms and life in the palace. It should be noted, however, that this is a point hotly debated among scholars, as is the whole of the so-called Amarna Period of Akhenaten’s rule. The preponderance of the evidence, both from the Amarna letters and from Tutankhamun’s later decree, as well as archaeological indications, strongly suggests that Akhenaten was a very poor ruler as far as his subjects and vassal states were concerned and his reign, in the words of Hawass, was “an inward-focused regime that had lost interest in its foreign policy”

Any evidence that Akhenaten involved himself in matters outside of his city at Akhetaten always comes back to self-interest rather than state-interest. Hawass writes:

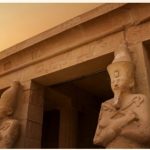

Akhenaten did not, however, abandon the rest of the country and retire exclusively to Akhetaten. When he laid out his city, he also commanded that a series of boundary stelae be carved in the cliffs surrounding the site. Among other things, these state that if he were to die outside of his home city, his body should be brought back and buried in the tomb that was being prepared for him in the eastern cliffs. There is evidence that, as Amenhotep IV, he carried out building projects in Nubia, and there were temples to the Aten in Memphis and Heliopolis, and possibly elsewhere as well.