The practice of mummifying the dead began in ancient Egypt c. 3500 BCE. The English word mummy comes from the Latin mumia which is derived from the Persian mum meaning ‘wax’ and refers to an embalmed corpse which was wax-like. The idea of mummifying the dead may have been suggested by how well corpses were preserved in the arid sands of the country.

Early graves of the Badarian Period (c. 5000 BCE) contained food offerings and some grave goods, suggesting a belief in an afterlife, but the corpses were not mummified. These graves were shallow rectangles or ovals into which a corpse was placed on its left side, often in a fetal position. They were considered the final resting place for the deceased and were often, as in Mesopotamia, located in or close by a family’s home.

Graves evolved throughout the following eras until, by the time of the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE), the mastaba tomb had replaced the simple grave, and cemeteries became common. Mastabas were seen not as a final resting place but as an eternal home for the body. The tomb was now considered a place of transformation in which the soul would leave the body to go on to the afterlife. It was thought, however, that the body had to remain intact in order for the soul to continue its journey.

Once freed from the body, the soul would need to orient itself by what was familiar. For this reason, tombs were painted with stories and spells from The Book of the Dead, to remind the soul of what was happening and what to expect, as well as with inscriptions known as The Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts which would recount events from the dead person’s life. Death was not the end of life to the Egyptians but simply a transition from one state to another. To this end, the body had to be carefully prepared in order to be recognizable to the soul upon its awakening in the tomb and also later.

The Osiris Myth & Mummification

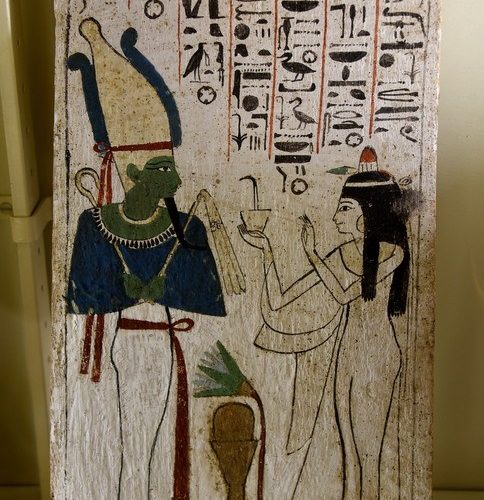

By the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE), mummification had become standard practice in handling the deceased and mortuary rituals grew up around death, dying, and mummification. These rituals and their symbols were largely derived from the cult of Osiris who had already become a popular god. Osiris and his sister-wife Isis were the mythical first rulers of Egypt, given the land shortly after the creation of the world. They ruled over a kingdom of peace and tranquility, teaching the people the arts of agriculture, civilization, and granting men and women equal rights to live together in balance and harmony.

Osiris’ brother, Set, grew jealous of his brother’s power and success, however, and so murdered him; first by sealing him in a coffin and sending him down the Nile River and then by hacking his body into pieces and scattering them across Egypt. Isis retrieved Osiris’ parts, reassembled him, and then with the help of her sister Nephthys, brought him back to life. Osiris was incomplete, however – he was missing his penis which had been eaten by a fish – and so could no longer rule on earth. He descended to the underworld where he became Lord of the Dead. Prior to his departure, though, Isis had mated with him in the form of a kite and bore him a son, Horus, who would grow up to avenge his father, reclaim the kingdom, and again establish order and balance in the land.

This myth became so incredibly popular that it infused the culture and assimilated earlier gods and myths to create a central belief in a life after death and the possibility of resurrection of the dead. Osiris was often depicted as a mummified ruler and regularly represented with green or black skin symbolizing both death and resurrection. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson writes:

HE CULT OF OSIRIS BEGAN TO EXERT INFLUENCE ON THE MORTUARY RITUALS AND THE IDEALS OF CONTEMPLATING DEATH AS A “GATEWAY INTO ETERNITY”. THIS DEITY, HAVING ASSUMED THE CULTIC POWERS AND RITUALS OF OTHER GODS OF THE NECROPOLIS, OR CEMETERY SITES, OFFERED HUMAN BEINGS SALVATION, RESURRECTION, AND ETERNAL BLISS.

Eternal life was only possible, though, if one’s body remained intact. A person’s name, their identity, represented their immortal soul, and this identity was linked to one’s physical form.

Parts of the Soul

The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts:

- The Khat was the physical body.

- The Ka one’s double-form (astral self).

- The Ba was a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens (specifically between the afterlife and one’s body)

- The Shuyet was the shadow self.

- The Akh was the immortal, transformed self after death.

- The Sahu was an aspect of the Akh.

- The Sechem was another aspect of the Akh.

- The Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil, holder of one’s character.

- The Ren was one’s secret name.

The Khat needed to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and be able to function properly. Once released from the body, these different aspects would be confused and would at first need to center themselves by some familiar form