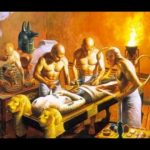

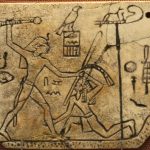

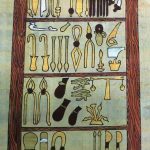

Metallurgy was carried on with an elaborate technique and a business organization not unworthy of the modern world, while the systematic exploitation of mines was an important industry employing many thousands of workers. Even as early as 3400 B.C., at the beginning of the historical period, the Egyptians had an intimate knowledge of copper ores and of processes of extracting the metal. During the fourth and subsequent dynasties (i.e. from about 2900 B.C. onwards), metals seem to have been entirely monopolies of the Court, the management of the mines and quarries being entrusted to the highest officials and sometimes even to the sons of the Pharaoh.

Whether these exalted personages were themselves professional metallurgists we do not know, but we may at least surmise that the details of metallurgical practice, being of extreme importance to the Crown, were carefully guarded from the vulgar. And when we remember the close association between the Egyptian royal family and the priestly class we appreciate the probable truth of the tradition that chemistry first came to light in the laboratories of Egyptian prie

The Egyptians called iron ‘the metal of heaven’ or ba-en-pet, which indicates that the first specimen employed were of meteoric origin; the Babylonian name having the same meaning.

It was no doubt on account of its rarity that iron was prized so highly by the early Egyptians, while its celestial source would have its fascination. Strange to say, it was not used for decorative, religious or symbolical purposes, which – coupled with the fact that it rusts so readily – may explain why comparatively few iron objects of early dynastic age have been discovered.

One which has fortunately survived presents several points of interest: it is an iron tool from the masonry of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza, and thus presumably dates from the time when the Pyramid was being built, i.e. about 2900 B.C. This tool was subjected to chemical analysis and was found to contain combined carbon, which suggests that it may have been composed of steel.

By 666 B.C. the process of casehardening was in use for the edges of iron tools, but the story that the Egyptians had some secret means of hardening copper and bronze that has since been lost is probably without foundation. Desch has shown that a hammered bronze, containing 10.34 per cent of tin, is considerably harder than copper and keeps a cutting edge much better.

Of the other non-precious metals, tin was used in the manufacture of bronze, and cobalt has been detected as a coloring agent in certain specimens of glass and glaze. Neither metal occurs naturally in Egypt, and it seems probable that supplies of ore were imported from Persia. Lead, though it never found extensive application, was among the earliest metals known, specimen having been found in graves of pre-dynastic times. Galena (PbS) was mined in Egypt at Gebel Rasas (‘Mountain of Lead’), a few miles from the Red Sea coast, and the supply must have been fairly good, for when the district was re-worked from 19I2 to 1915 it produced more than I8,000 tons of ore.

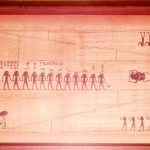

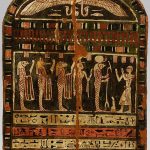

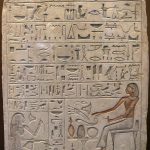

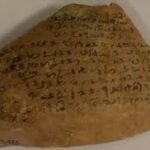

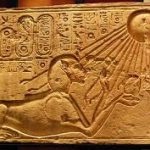

Of one of these mines – possibly near Apollinopolis – a plan has been found in a papyrus of the fourteenth century B.C., and the remains of no fewer than 1,300 houses for gold-miners are still to be seen in the Wadi Fawakhir, halfway between Koptos and the Red Sea. In one of the treasure chambers of the temple of Rameses III, at Medinet-Habu, are represented eight large bags, seven of which contained gold and bear the following descriptive labels.

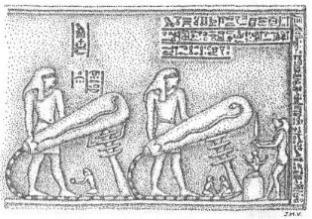

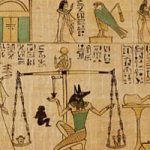

The Egyptian word for gold is nub, which survives in the name Nubia, a country that provided a great deal of the precious metal in ancient days. French Scientist Champollion regarded it as a kind of crucible, while Rossellini and Lepsius preferred to see in it a bag or cloth, with hanging ends, in which the grains of gold were washed – the radiating lines representing the streams of water that ran through.

In the later dynasties, the Egyptians themselves forgot the original significance of the sign and drew it as a necklace with pendent beads. Elliot Smith however says that this was the primitive form and became the determinative of Hathor, the Egyptian Aphrodite, who was the guardian of the Eastern valleys where gold was found.