In the biblical Book of Luke, the story is told of Lazarus and the Rich Man in which a man of wealth and the poorest beggar both die on the same day. The beggar, Lazarus, finds himself in paradise while the rich man is in torment. He looks up to see Father Abraham with Lazarus beside him and asks if Lazarus might bring him some water, but this is denied; there is a great chasm fixed between those in heaven and those in hell, and none may cross. The rich man then asks if Abraham could send Lazarus back to the world of the living to warn his family because, he says, he has five brothers who are all living the same self-indulgent lifestyle he enjoyed and he does not want them to suffer the same fate. When Abraham answers, saying “They have Moses and the prophets; let them listen to them,” the rich man responds that his brothers will not listen to scripture, but if someone should come back from the dead, they would surely listen to him. Abraham then says, “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead” (Luke 16:19-31).

This story has been interpreted in many different ways over the centuries in order to make various theological points, but its theme is timeless: what happens after death? The rich man thought he was living a good life but finds himself in the worst kind of afterlife while Lazarus, who suffered on earth, is welcomed to a reward in heaven. The request of the rich man to send Lazarus back to earth sounds reasonable in that if someone came back from the dead to tell what it was like, people would certainly listen and live their lives differently; Abraham, however, denies the request.

Abraham’s response, however disappointing it might seem to the rich man, is an accurate assessment of the situation. In the present day, people’s stories of Near Death Experiences are accepted by those who already believe in that kind of afterlife and are denied by those who do not. Even if someone should come back from the dead, if one cannot accept that kind of reality, one will not believe their story and, in this same way, will certainly not accept ancient stories regarding the same kind of event.

In ancient Egypt, however, the afterlife was a certainty throughout most of the civilization’s history. When one died, one’s soul went on to another plane, leaving the body behind, and hoped for justification by the gods and an eternal life in paradise. There was no doubt that this afterlife existed, save during the period of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), and even then the literature which expresses cynicism toward the next life could be interpreted as a literary device as easily as a serious theological challenge. The soul of a loved one did not cease to exist at death nor was there any danger of a surprise in the afterlife such as the rich man from Luke experiences.

An exception is in the fictional work from Roman Egypt (30 BCE – 646 CE) known as Setna II, which is the probable basis for the Luke tale. In one part of Setna II, Si-Osire leads his father Setna to the underworld and shows him how a rich man and a poor man experienced the afterlife. Contrary to Setna’s earlier understanding that a wealthy man would be happier than the poor, the rich man suffers in the underworld and the poor man is elevated. Si-Osire leads his father to the afterlife to correct his misunderstanding, and their short trip there illustrates the closeness ancient Egyptians felt to the next world. The dead lived on and, if one wanted to, one could even communicate with them. These communications are known today as ‘letters to the dead’.

The Egyptian Afterlife & the Dead

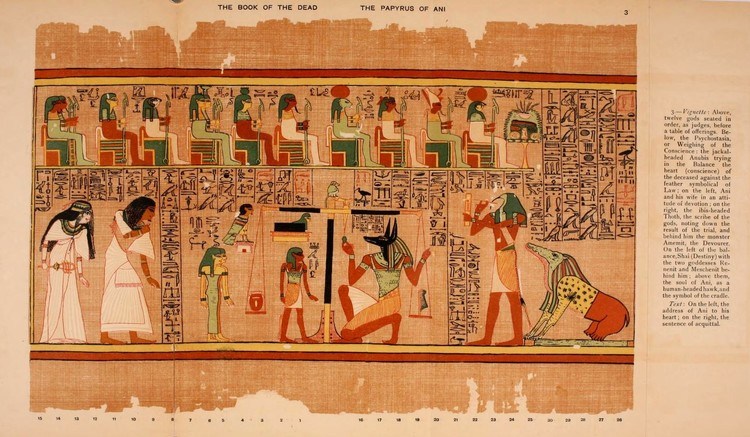

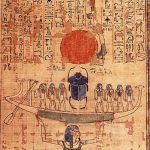

It was believed that, after one died and the proper mortuary rituals had been observed, one passed on to judgment before Osiris and his tribunal, and if one had lived a good life, one was justified and passed on to paradise. The question of ‘What is a good life?’ was answered through the recitation of the Negative Confession before the tribunal of Osiris and the weighing of the heart in the balance against the white feather of truth, but even before one’s death, one would have a fairly good idea of one’s chances in the Hall of Truth.

The Egyptians did not rely on ancient texts to instruct them on moral behavior but on the principle of ma’at, harmony and balance, which encouraged them to live in peace with the earth and with their neighbors. Certainly, this principle was illustrated in religious stories, embodied in the goddess of the same name, invoked in written works such as medical texts and hymns, but it was a living concept which one could measure one’s success in meeting daily. One would not need someone to come back from the dead with a warning; one’s actions in life and their consequences would be enough – or should have been – to give a person a fairly good indication of what awaited them after death.

The justified dead, now in paradise, had the ear of the gods and could be persuaded to intercede on people’s behalf in answering questions, predicting the future, or defending the petitioner against injustice. The gods had created a world of harmony, and all one needed to do in order to reach paradise in the next was to live a life worthy of eternity. If one made each day an exercise in creating a life one would wish to continue forever, founded on the concept of harmony and balance (which of course included consideration and kindness for one’s neighbors), one could be confident of entry to paradise after death.

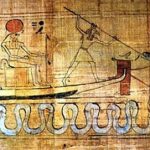

Still, there were supernatural forces at work in the universe which could cause one problems along life’s path. Evil demons, angry gods, and the unhappy or vengeful spirits of the dead could all interfere with one’s health and happiness at any time and for any reason. Simply because one was favored by a god, like Thoth, in one’s life and career did not mean that another, like Set, could not bring one grief. Further, there were simply the natural difficulties of existence which troubled the soul and threw one off balance such as sickness, disappointment, heartbreak, and death of a loved one. When these kinds of troubles, or those more mysterious, came upon a person, there was something direct they could do about it: write a letter to the dead.

History & Purpose

Letters to the Dead date from the Old Kingdom (c. 2613 – 2181 BCE) through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), essentially the entirety of Egyptian history. When a tomb was constructed, depending upon one’s wealth and status, an offerings chapel was also built so that the soul could receive food and drink offerings on a daily basis. The letters to the dead, often written on an offering bowl, would be delivered to these chapels along with the food and drink and would then be read by the soul of the departed. Egyptologist David P. Silverman notes how “In most cases, however, interaction between the living and the dead would have been more casual, with spoken prayers that have left no trace” (142). It is for this reason that so few letters to the dead exist today but, even so, enough do to understand their intent and importance.

One would write a letter in the same way one wrote to a person still living. Silverman explains:

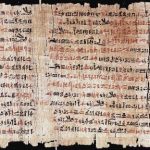

Whether inscribed on pottery bowls, linen, or papyrus, these documents take the form of standard letters, with notations of addressee and sender and, depending upon the tone of the letter, a salutation: “A communication by Merirtyfy to Nebetiotef: How are you? Is the West taking care of you as you desire?”

The ‘west’, of course, is a reference to the land of the dead, which was thought to be located in that direction. Osiris was known as the ‘First of the Westerners’ in his position as Lord of the Dead. As Silverman and others note, a response was expected to these letters since Spell 148 and Spell 190 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead enabled a spirit to let the living know how it was doing in the afterlife.

Once salutations and pleasantries were expressed, the sender would get to the matter of the message and this was always a request for an intercession of some kind. Often, the writer reminds the recipient of some kindness they performed for them or the life they lived happily together on earth. Egyptologist Gay Robins cites one of these:

A man points out in a letter to his dead wife that he married her ‘when I was a young man. I was with you when I was carrying out all sorts of offices. I was with you and I did not divorce you. I did not cause your heart to grieve. I did it when I was a youth and when I was carrying out all sorts of important offices for Pharaoh, life, propsperity, health, without divorcing you, saying “She has always been with me- so said I!”‘ In other words, as men climbed the bureaucratic ladder, it was probably not unknown for them to divorce the wives of their youth and remarry a woman more appropriate or advantageous to their higher rank.

This husband reminds his wife of how faithful and dutiful he was to her prior to making his request for her help with his problem. Egyptologist Rosalie David notes how “requests found in the letters are varied: some sought help against dead or living enemies, particularly in family disputes; others asked for legal assistance in support of a petitioner who had to appear before the divine tribunal at the Day of Judgment; and some pleaded for special blessings or benefits” (282). The most often made requests, however, deal with fertility and birth through appeals for a healthy pregnancy and child, most often a son.