A writer would receive a response from the dead in a number of different ways. One could hear from the deceased in a dream, receive some message or ‘sign’ in the course of a day, consult a seer, or simply find one’s problem suddenly resolved. The dead, after all, were in the company of the gods, and the gods were known to exist and, further, to mean only the best for human beings. There was no reason to doubt that one’s request had been heard and that one would receive an answer.

Osiris was the lord of justice, and it only made sense that a soul in his presence would have greater influence than one still in the body on earth. Should this seem strange or ‘archaic’ to a modern-day reader, it should be remembered that there are many who observe this same belief today. The souls of the departed, especially those considered holy, are still thought to have more pull with the divine than someone on earth. Silverman comments:

In all cases, the deceased is urged to take action on behalf of the writer, often against malignant spirits who have afflicted the author and his or her family. Such requests frequently refer to the underworld court and the role of the deceased within it: “you must instigate litigation with him since you have witnesses at hand in the same city of the dead”. The principle is stated succinctly on a bowl in the Louvre in Paris: “As you were one who was excellent upon earth, so you are one who is in good standing in the necropolis”. Despite this legalistic aspect, the letters are never formulaic but vary in content and length.

Clearly, writing to someone in the afterlife was the same as writing to one in another city on earth. There is almost no difference between the two types of correspondence. A letter written in the 2nd century CE from a young woman named Sarapias to her father follows roughly the same model:

Sarapias to Ammonios, her father and lord, many greetings. I constantly pray that you are well and I make obeisance on your behalf before Philotera. I left Myos Hormos quickly after giving birth. I have taken nothing from Myos Hormos…Send me 1 small drinking cup and send your daughter a small pillow.

The only difference between this letter and one a son writes to his deceased mother (c. First Intermediate Period of Egypt, 2181-2040 BCE) is that Sarapias asks for material objects to be sent while the son requests spiritual intervention. The son begins his letter with a similar salutation and then, just as Sarapias explains how she needs a cup and pillow sent, makes his request for aid. He also reminds his mother of how dutiful a son he was while she lived, writing, “You did say this to your son, ‘Bring me quails that I may eat them’, and this your son brought to you, seven quails, and you did eat them” (Robins, 107). Letters like this one also make clear to the deceased that the writer has not ‘garbled a spell’ in performing the necessary rituals. This would be most important in making sure that the soul of the deceased continued to be remembered so it could live well in the afterlife.

Once the soul had read the letter, the writer had only to be patient and wait for a response. If the writer had committed no sins and had performed all the rituals properly, they would receive a positive response in some fashion. After making their requests, the writers frequently promised gifts in return and assurances of good conduct. Robins comments on this:

In a First Intermediate Period letter to the dead, a husband tells his wife: ‘I have not garbled a spell before you, while making your name to live upon the earth’, and he promises to do more for her if she cures him of his illness: ‘I shall lay down offerings for you when the sun’s light has risen and I shall establish an altar for you’. The woman’s brother also asks for help and he says, ‘I have not garbled a spell before you; I have not taken offerings away from you’.

Since the dead person retained their personal identity in the next world, one would write them using the same kinds of touches that had worked in life. If one had gotten their way through threats, then threats were used such as suggesting that, if one did not get one’s wish, one would cut off offerings at the tomb. Offerings were made to the gods in their shrines and temples regularly, and the gods clearly heard and responded, and so it was thought the dead did the same. The problem with such threats would be that, if one stopped bringing offerings, one was more likely to be haunted by an angry spirit than have their request granted. Just as the gods frowned on petulant people’s impiety in withholding offerings, so did the dead.

Conclusion

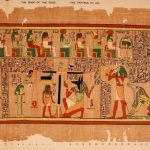

Every ancient culture had some concept regarding the afterlife, but Egypt’s was the most comprehensive and certainly the most ideal. Egyptologist Jan Assman notes:

The widespread prejudice that theology is the exclusive achievement of biblical, if not Christian, religion is unfounded with regard to ancient Egypt. On the contrary, Egyptian theology is much more elaborate than anything that can be found in the Bible.

The Egyptians left nothing to chance – as can be observed in the technical skill evident in the monuments and temples which still stand – and this was as true of their view of eternity as anything else. Every action in one’s life had a consequence not only in the present but for eternity. Life on earth was only one part of an everlasting journey and one’s behavior affected one’s short-term and long-term future. One could feel assured of what awaited after life by measuring one’s actions against the standard of harmonious existence and the example set by the gods and the natural world.

The Egyptian version of the story in Luke, though similar, is significantly different. The rich man in Setna II would expect to find punishment in the next life for ignoring the principle of ma’at. The beggar in the story would not have expected, nor been entitled to, a reward simply for suffering. Everyone suffered, after all, at one time or another, and the gods owed no one any special recognition for that.

In Setna II, the rich and poor man are punished and rewarded because their actions on earth either dishonored or honored ma’at, and, while others may have envied or pitied them, they could have expected what awaited them beyond death. In the Christianized version of Setna II which appears in Luke, neither the rich man nor Lazarus has any idea what is waiting for them. The Luke version of the story, in fact, would have probably been confusing to an ancient Egyptian who, if they had a question concerning the afterlife and what waited beyond, could simply write a letter and ask.