Agriculture was the foundation of the ancient Egyptian economy and vital to the lives of the people of the land. Agricultural practices began in the Delta Region of northern Egyptand the fertile basin known as the Faiyum in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 – c. 3150 BCE), but there is evidence of agricultural use and overuse of the land dating back to 8000 BCE.

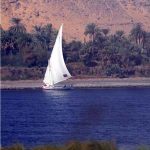

Egyptologist and historian Margaret Bunson defines ancient Egyptian agriculture as “the science and practice of the ancient Egyptians from predynastic times that enabled them to transform an expanse of semiarid land into rich fields after each inundation of the Nile” (4). In this, she is referring to the yearly flooding of the Nile River which rose over its banks to deposit nutrient-rich soil on the land, allowing for the cultivation of crops. Without the inundation, Egyptian culture could not have taken hold in the Nile River Valley and their civilization would never have been established. So important was the Nile flood that scholars believe many, if not most, of the best known Egyptian myths are linked to, or directly inspired by, this event. The story of the death and resurrection of the god Osiris, for example, is thought to have initially been an allegory for the life-giving inundation of the Nile, and numerous gods throughout Egypt’s history are directly or indirectly linked to the river’s flood.

So fertile were the fields of Egypt that, in a good season, they produced enough food to feed every person in the country abundantly for a year and still have surplus, which was stored in state-owned granaries and used in trade or saved for leaner times. A bad growing season was always the result of a shallow inundation by the Nile, no matter the amount of rainfall or what other factors came into play.

Tools & Practices

The yearly inundation was the most important aspect of Egyptian agriculture, but the people obviously still needed to work the land. Fields had to be plowed and seed sown and water moved to different areas, which led to the invention of the ox-drawn plow and improvements in irrigation. The ox-drawn plow was designed in two gauges: heavy and light. The heavy plow went first and cut the furrows while the lighter plow came behind turning up the earth.

Once the field was plowed, then workers with hoes broke up the clumps of soil and sowed the rows with seed. These hoes were made of wood and were short-handled (most likely because wood was scarce in Egypt and so wooden products were expensive) and so to work with them was extremely labor-intensive. A farmer could expect to spend most of a day literally bent over the hoe.

Once the ground was broken and the clods dispersed, seed was carried to the field in baskets and workers filled smaller baskets or sacks from these larger containers. The most common means of sowing the earth was to carry a basket in one arm while flinging the seed with the other hand.

Canals

Egyptian irrigation techniques were so effective they were implemented by the cultures of Greece and Rome. Irrigation was not an Egyptian invention, however, but was introduced during the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782 – c.1570 BCE) by the people known as the Hyksos, who settled in Avaris in Lower Egypt; the Egyptians simply improved upon the techniques. The yearly inundation of the Nile was essential to Egyptian life, but irrigation canals were necessary to carry water to outlying farms and villages as well as to maintain even saturation of crops near the river. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson notes how the Delta Region of Lower Egypt was far more fertile than the fields of Upper Egypt toward the south and so “the Upper Egyptian farmer had to be inventive and, at an early date, learned to cooperate with his neighbours in harnessing the river water through the building of irrigation canals and drainage ditches” (40).

These canals were carefully engineered to efficiently water the fields but, most importantly, not to interfere with anyone else’s crops or canals. This aspect of canal construction was so important that it was included in the Negative Confession, the proclamation a soul would make after death when it stood in judgment. Among the Confessions are numbers 33 and 34 in which the soul claims it has never obstructed water in another’s canal and has never cut into someone else’s canal illegally. After receiving permission to dig a canal, estate owners and farmers were responsible for the proper construction and maintenance of it. Bunson writes:

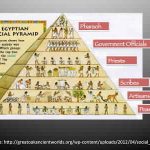

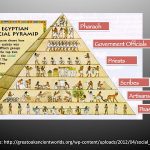

Early farmers dug trenches from the Nile shore to the farmlands, using draw wells and then the Shaduf, a primitive machine that allowed them to raise levels of water from the Nile into canals…Fields thus irrigated produced abundant annual crops. From the predynastic times agriculture was the mainstay of the Egyptian economy. Most Egyptians were employed in agricultural labors, either on their own lands or on the estates of the temples or nobles. Control of irrigation became a major concern and provincial officials were held responsible for the regulation of water.

Bunson is here referring not only to disputes between people over water rights but the almost sacred responsibility of officials to ensure that water was not wasted, which included making certain that canals were kept in good working order. The regional governor (nomarch) of a certain district (nome) delegated authority to those under him for the building of state-sponsored canals and for the maintenance of both public and private waterways. Fines were levied for improperly constructed or poorly maintained canals which wasted water or on those who diverted water from others without permission.

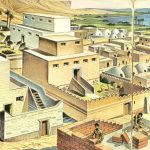

The state-sponsored canals were often ornate works of art. When Ramesses II the Great (1279-1213 BCE) built his city of Per-Ramesses at the site of ancient Avaris, his canals were said to be the most impressive in all of Egypt. These public works were elaborately ornamented while, at the same time, functioning with such high efficiency that the entire region around Per-Ramesses flourished. Hydraulics were used from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) onwards to drain land and move water efficiently through the land. An abundance of crops not only meant that the people were well fed but that the economy would thrive through trade of agricultural goods.