Active and independent individuals, women in Ancient Egypt enjoyed a legal equality with men that their sisters in the modern world did not manage until the 20th century, and a financial equality that many have yet to achieve.

Whilst the concept of a career choice for women is a relatively modern phenomenon, the situation in ancient Egypt was rather different. For some three thousand years the women who lived on the banks of the Nile enjoyed a form of equality which has rarely been equalled.

Sexual equality

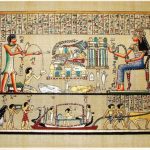

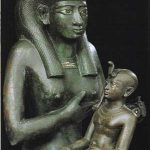

In order to understand their relatively enlightened attitudes toward sexual equality, it is important to realise that the Egyptians viewed their universe as a complete duality of male and female. Giving balance and order to all things was the female deity Maat, symbol of cosmic harmony by whose rules the pharaoh must govern.

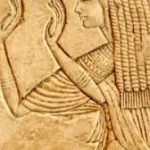

The Egyptians recognised female violence in all its forms, their queens even portrayed crushing their enemies, executing prisoners or firing arrows at male opponents as well as the non-royal women who stab and overpower invading soldiers. Although such scenes are often disregarded as illustrating ‘fictional’ or ritual events, the literary and archaeological evidence is less easy to dismiss. Royal women undertake military campaigns whilst others are decorated for their active role in conflict. Women were regarded as sufficiently threatening to be listed as ‘enemies of the state’, and female graves containing weapons are found throughout the three millennia of Egyptian history.

Royal women undertook military campaigns whilst others were decorated for their active role in conflict. Women were regarded as sufficiently threatening to be listed as ‘enemies of the state’, and female graves containing weapons are found throughout the three millennia of Egyptian history.

Although by no means a race of Amazons, their ability to exercise varying degrees of power and self-determination was most unusual in the ancient world, which set such great store by male prowess, as if acknowledging the same in women would make them less able to fulfil their expected roles as wife and mother. Indeed, neighbouring countries were clearly shocked by the relative freedom of Egyptian women and, describing how they ‘attended market and took part in trading whereas men sat and home and did the weaving’, the Greek historian Herodotus believed the Egyptians ‘have reversed the ordinary practices of mankind’.

And women are indeed portrayed in a very public way alongside men at every level of society, from co-ordinating ritual events to undertaking manual work. One woman steering a cargo ship even reprimands the man who brings her a meal with the words, ‘Don’t obstruct my face while I am putting to shore’ (the ancient version of that familiar conversation ‘get out of my way whilst I’m doing something important’).

Egyptian women also enjoyed a surprising degree of financial independence, with surviving accounts and contracts showing that women received the same pay rations as men for undertaking the same job – something the UK has yet to achieve. As well as the royal women who controlled the treasury and owned their own estates and workshops, non-royal women as independent citizens could also own their own property, buy and sell it, make wills and even choose which of their children would inherit.

Ladies of leisure

The most common female title ‘Lady of the House’ involved running the home and bearing children, and indeed women of all social classes were defined as wives and mothers first and foremost. Yet freed from the necessity of producing large numbers of offspring as an extra source of labour, wealthier women also had alternative ‘career choices’.

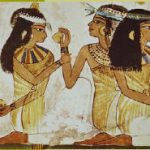

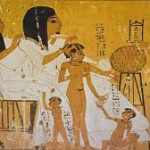

After being bathed, depilated and doused in sweet heavy perfumes, queens and commoners alike are portrayed sitting patiently before their hairdressers, although it is equally clear that wigmakers enjoyed a brisk trade. The wealthy also employed manicurists and even female make-up artists, whose title translates literally as ‘painter of her mouth’. Yet the most familiar form of cosmetic, also worn by men, was the black eye paint which reduced the glare of the sun, repelled flies and looked rather good.

Women are indeed portrayed in a very public way alongside men at every level of society, from co-ordinating ritual events to undertaking manual work.

Dressing in whatever style of linen garment was fashionable, from the tight-fitting dresses of the Old Kingdom (c.2686 – 2181 BC) to the flowing finery of the New Kingdom (c.1550 – 1069 BC), status was indicated by the fine quality of the linen, whose generally plain appearance could be embellished with coloured panels, ornamental stitching or beadwork. Finishing touches were added with various items of jewellery, from headbands, wig ornaments, earrings, chokers and necklaces to armlets, bracelets, rings, belts and anklets made of gold, semi-precious stones and glazed beads.

With the wealthy ‘lady of the house’ swathed in fine linen, bedecked in all manner of jewellery, her face boldly painted and wearing hair which more than likely used to belong to someone else, both male and female servants tended to her daily needs. They also looked after her children, did the cleaning and prepared the food, although interestingly the laundry was generally done by men.

Freed from such mundane tasks herself, the woman could enjoy all manner of relaxation, listening to music, eating good food and drinking fine wine. One female party-goer even asked for ‘eighteen cups of wine for my insides are as dry as straw’. Women are also portrayed with their pets, playing board games, strolling in carefully tended gardens or touring their estates. Often travelling by river, shorter journeys were also made by carrying-chair or, for greater speed, women are even shown driving their own chariots.

Women at the top

The status and privileges enjoyed by the wealthy were a direct result of their relationship with the king, and their own abilities helping to administer the country. Although the vast majority of such officials were men, women did sometimes hold high office. As ‘Controller of the Affairs of the Kiltwearers’, Queen Hetepheres II ran the civil service and, as well as overseers, governors and judges, two women even achieved the rank of vizier (prime minister). This was the highest administrative title below that of pharaoh, which they also managed on no fewer than six occasions.

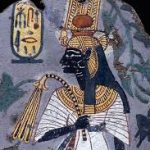

Egypt’s first female king was the shadowy Neithikret (c.2148-44 BC), remembered in later times as ‘the bravest and most beautiful woman of her time’. The next woman to rule as king was Sobeknefru (c.1787-1783 BC) who was portrayed wearing the royal headcloth and kilt over her otherwise female dress. A similar pattern emerged some three centuries later when one of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs, Hatshepsut, again assumes traditional kingly regalia. During her fifteen year reign (c.1473-1458 BC) she mounted at least one military campaign and initiated a number of impressive building projects, including her superb funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari.

Ancient Egyptian women enjoyed a surprising degree of financial independence, with surviving accounts and contracts showing that women received the same pay rations as men for undertaking the same job – something the UK has yet to achieve!

But whilst Hatshepsut’s credentials as the daughter of a king are well attested, the origins of the fourth female pharaoh remain highly controversial. Yet there is far more to the famous Nefertiti than her dewy-eyed portrait bust. Actively involved in her husband Akhenaten’s restructuring policies, she is shown wearing kingly regalia, executing foreign prisoners and, as some Egyptologists believe, ruling independently as king following the death of her husband c.1336 BC. Following the death of her husband Seti II in 1194 BC, Tawosret took the throne for herself and, over a thousand years later, the last of Egypt’s female pharaohs, the great Cleopatra VII, restored Egypt’s fortunes until her eventual suicide in 30 BC marks the notional end of ancient Egypt.

Wives and mothers

But with the ‘top job’ far more commonly held by a man, the most influential women were his mother, sisters, wives and daughters. Yet, once again, many clearly achieved significant amounts of power as reflected by the scale of monuments set up in their name. Regarded as the fourth pyramid of Giza, the huge tomb complex of Queen Khentkawes (c.2500 BC) reflects her status as both the daughter and mother of kings. The royal women of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs were again given sumptuous burials within pyramid complexes, with the gorgeous jewellery of Queen Weret discovered as recently as 1995.

During Egypt’s ‘Golden Age’, (the New Kingdom, c.1550-1069 BC), a whole series of such women are attested, beginning with Ahhotep whose bravery was rewarded with full military honours. Later, the incomparable Queen Tiy rose from her provincial beginnings as a commoner to become ‘great royal wife’ of Amenhotep III (1390-1352 BC), even conducting her own diplomatic correspondence with neighbouring states.

Pharaohs also had a host of ‘minor wives’ but, since succession did not automatically pass to the eldest son, such women are known to have plotted to assassinate their royal husbands and put their sons on the throne. Given their ability to directly affect the succession, the term ‘minor wife’ seems infinitely preferable to the archaic term ‘concubine’.

Yet even the word ‘wife’ can be problematic, since there is no evidence for any kind of legal or religious marriage ceremony in ancient Egypt. As far as it is possible to tell, if a couple wanted to be together, the families would hold a big party, presents would be given and the couple would set up home, the woman becoming a ‘lady of the house’ and hopefully producing children.

Women often held high offices in Ancient Egypt, and the records show that more than six were anointed pharaohs, others ran the civil service and, as well as overseers, governors and judges, two women even achieved the rank of vizier (prime minister).

Whilst most chose partners of a similar background and locality, some royal women came from as far afield as Babylon and were used to seal diplomatic relations. Amenhotep III described the arrival of a Syrian princess and her 317 female attendants as ‘a marvel’, and even wrote to his vassals – ‘I am sending you my official to fetch beautiful women, to which I the king will say good. So send very beautiful women – but none with shrill voices’!

Such women were given the title ‘ornament of the king’, chosen for their grace and beauty to entertain with singing and dancing. But far from being closeted away for the king’s private amusement, such women were important members of court and took an active part in royal functions, state events and religious ceremonies.

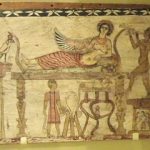

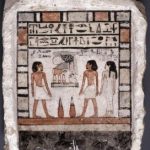

With the wives and daughters of officials also shown playing the harp and singing to their menfolk, women seem to have received musical training. In one tomb scene of c.2000 BC a priest is giving a kind of masterclass in how to play the sistrum (sacred rattle), as temples often employed their own female musical troupe to entertain the gods as part of the daily ritual.

Careers

In fact, other than housewife and mother, the most common ‘career’ for women was the priesthood, serving male and female deities. The title, ‘God’s Wife’, held by royal women, also brought with it tremendous political power second only to the king, for whom they could even deputise. The royal cult also had its female priestesses, with women acting alongside men in jubilee ceremonies and, as well as earning their livings as professional mourners, they occasionally functioned as funerary priests.

A brilliant linguist, Cleopatra VII, endowed the Great Library at Alexandria, the intellectual capital of the ancient world where female lecturers are known to have participated alongside their male colleagues. Yet an equality which had existed for millennia was ended by Christianity – the philosopher Hypatia was brutally murdered by monks in 415 AD as a graphic demonstration of their beliefs.

Their ability to undertake certain tasks would be even further enhanced if they could read and write but, with less than 2% of ancient Egyptian society known to be literate, the percentage of women with these skills would be even smaller. Although it is often stated that there is no evidence for any women being able to read or write, some are shown reading documents. Literacy would also be necessary for them to undertake duties which at times included prime minister, overseer, steward and even doctor, with the lady Peseshet predating Elizabeth Garret Anderson by some 4,000 years.

By Graeco-Roman times women’s literacy is relatively common, the mummy of the young woman Hermione inscribed with her profession ‘teacher of Greek grammar’. A brilliant linguist herself, Cleopatra VII endowed the Great Library at Alexandria, the intellectual capital of the ancient world where female lecturers are known to have participated alongside their male colleagues. Yet an equality which had existed for millennia was ended by Christianity – the philosopher Hypatia was brutally murdered by monks in 415 AD as a graphic demonstration of their beliefs.

With the concept that ‘a woman’s place is in the home’ remaining largely unquestioned for the next 1,500 years, the relative freedom of ancient Egyptian women was forgotten. Yet these active, independent individuals had enjoyed a legal equality with men that their sisters in the modern world did not manage until the 20th century, and a financial equality that many have yet to achieve.