When we think of ancient Egyptians, the image that most readily pops into our minds is hordes of workers labouring to build a colossal pyramid, while whip-wielding overseers brutally urge them onwards. Alternatively, we imagine Egyptian priests chanting invocations as they conspired to resurrect a mummy.

Happily, the reality for ancient Egyptians was quite different. Most Egyptians believed life in ancient Egypt was so divinely perfect, that their vision of the afterlife was an eternal continuation of their earthly life.

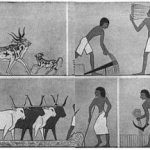

The artisans and labourers who built Egypt’s colossal monuments, magnificent temples and eternal pyramids were well paid for their skills and their labour. In the case of the artisans, they were recognized as masters of their craft.

Facts About Daily Life in Ancient Egypt

- Ancient Egyptian society was very conservative and highly stratified from the Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE) onwards

- Most ancient Egyptians believed life was so divinely perfect, that their vision of the afterlife was an eternal continuation of their earthly existence

- The ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife where death was merely a transition

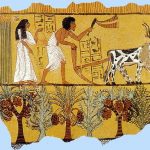

- Up until the Persian invasion of c. 525 BCE, the Egyptian economy used a barter system right and was based on agriculture and herding

- Daily life in Egypt focused on enjoying their time on earth as much as possible

- Ancient Egyptians spent time with family and friends, played games and sports and attended festivals

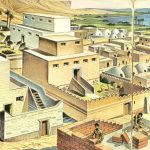

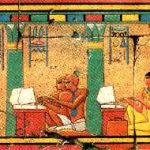

- Homes were built from sun-dried mud bricks and had flat roofs, making them cooler inside and allowing people to sleep on the roof in summer

- Houses featured central courtyards where the cooking was done

- Children in ancient Egypt rarely wore clothes, but often wore protective amulets around their necks as child mortality rates were high

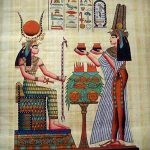

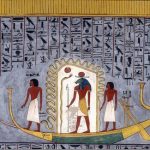

Role Of Their Belief In The Afterlife

Egyptian state monuments and even their modest personal tombs were built to honour their life. This was in recognition that a person’s life mattered sufficiently to be remembered across all eternity, be they the pharaoh or a humble farmer.

The fervent Egyptian belief in the afterlife where death was merely a transition, motivated the people to make their lives worth living eternally. Hence, daily life in Egypt focused on enjoying their time on earth as much as possible.

Magic, Ma’at And The Rhythm Of Life

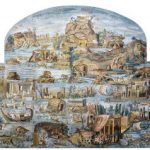

Life in ancient Egypt would be recognizable to a contemporary audience. Time with family and friends was rounded out with games, sports, festivals and reading. However, magic permeated the ancient Egypt world. Magic or heka was older than their gods and was the elemental force, which enabled the gods to carry out their roles. The Egyptian god Heka who did double duty as the god of medicine epitomized magic.

Another concept at the heart of daily Egyptian life was ma’at or harmony and balance. The quest for harmony and balance was fundamental to the Egyptian’s understanding of how their universe worked. Ma’at was the guiding philosophy that directed life. Heka enabled ma’at. By maintaining balance and harmony in their lives, people could peacefully coexist and collaborate communally.

Ancient Egyptians believed that being happy or allowing one’s face “shine” meant, would make one’s own heart light at the time of judgment and lighten those around them.

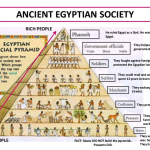

Ancient Egyptian Social Structure

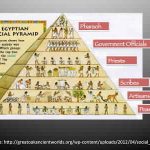

Ancient Egyptian society was very conservative and highly stratified from as early as Egypt’s Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE). At the top was the king, then came his vizier, members of his court, the “nomarchs” or regional governors, military generals after the New Kingdom, overseers of government worksites and the peasantry.

Social conservatism resulted in minimal social mobility for the majority of Egypt’s history. Most Egyptians believed the gods had ordained a perfect social order, which mirrored the gods own. The gods had gifted Egyptians with everything they needed and the king as their intermediary was the best equipped to interpret and enact their will.

From the Predynastic Period through to the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) it was the king who acted as the mediator between the gods and the people. Even during the late New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) when the Thebian priests of Amun had eclipsed the king in power and influence, the king remained respected as being divinely invested. It was the king’s responsibility to rule in keeping with the preservation of ma’at.