The kings still ruled from their capital of Memphis at the beginning of the First Intermediate Period, but they had very little actual power. The nomarchs administered their own regions, collected their own taxes, built their own temples and monuments in their honor, and commissioned their own tombs. The early kings of the First Intermediate Period (7th-10th dynasties) were so ineffectual that their names are hardly remembered and their dates are often confused. The nomarchs, on the other hand, grew steadily in power. Historian Margaret Bunson explains their traditional role prior to the First Intermediate Period:

The power of such local rulers was modified in times of strong pharaohs, but generally they served the central government, accepting the traditional role of being First Under The King. This rank denoted an official’s right to administer a particular nome or province on behalf of the pharaoh. Such officials were in charge of the region’s courts, treasury, land offices, conservation programs, militia, archives, and store-houses. They reported to the vizier and to the royal treasury on affairs within their jurisdiction. (103)

During the First Intermediate Period, however, the nomarchs used their growing resources to serve themselves and their communities. The kings of Memphis, perhaps in an attempt to regain some of their lost prestige, moved the capital to the city of Herakleopolis but were no more successful there than at the old capital.

C. 2125 BCE an overlord known as Intef I rose to power at a provincial city called Thebes in Upper Egypt and inspired his community to rebel against the kings of Memphis. His actions would inspire those who succeeded him and finally result in the victory of Mentuhotep II over the kings of Herakleopolis c. 2040 BCE, initiating the Middle Kingdom.

Mentuhotep II reigned from Thebes. Although he had ousted the old kings and begun a new dynasty, he patterned his rule on that of the Old Kingdom. The Old Kingdom was looked back on as a great age in Egypt’s history, and the pyramids and expansive complexes at Giza and elsewhere were potent reminders of the glory of the past. One of the old patterns he kept, which had been neglected during the latter part of the Old Kingdom, was duplication of agencies for Upper and Lower Egypt as Bunson explains:

In general, the administrative offices of the central government were exact duplicates of the traditional provincial agencies, with one significant difference. In most periods the offices were doubled, one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower Egypt. This duality was carried out in architecture as well, providing palaces with two entrances, two throne rooms, etc. The nation viewed itself as a whole, but there were certain traditions dating back to the legendary northern and southern ancestors, the semi-divine kings of the predynastic period, and to the concept of symmetry.

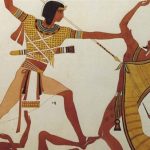

The duplication of agencies not only honored the north and the south of Egypt equally but, more importantly for the king, kept a tighter control of both regions. Mentuhotep II’s successor, Amenemhat I (c. 1991 – c.1962 BCE), moved the capital to the city of Iti-tawy near Lisht and continued the old policies, enriching the government quickly enough to begin his own building projects. His shifting of the capital from Thebes to Lisht may have been an attempt at further unifying Egypt by centering the government in the middle of the country instead of toward the south. In an effort which curbed the power of the nomarchs, Amenemhat I created the first standing army in Egypt directly under the king’s control. Prior to this, armies were raised by conscription in the different districts and the nomarch then sent his men to the king. This gave the nomarchs a great degree of power as the men’s loyalties lay with their community and regional ruler. A standing army, loyal first to the king, encouraged nationalism and a stronger unity.

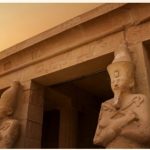

Amenemhat I’s successor, Senusret I (c. 1971-c.1926 BCE) continued his policies and further enriched the country through trade. It is Senusret I who first builds a temple to Amun at the site of Karnak and initiates the construction of one of the greatest religious structures ever built. The funds the government needed for such massive projects came from trade, and in order to trade the officials taxed the people of Egypt. Wilkinson explains how this worked:

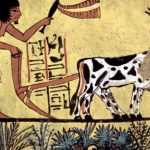

When it came to collecting taxes, in the form of a proportion of farm produce, we must assume a network of officials operated on behalf of the state throughout Egypt. There can be no doubt that their efforts were backed up by coercive measures. The inscriptions left by some of these government officials, mostly in the form of seal impressions, allow us to re-create the workings of the treasury, which was by far the most important department from the very beginning of Egyptian history. Agricultural produce collected as a government revenue was treated in one of two ways. A certain proportion went directly to state workshops for the manufacture of secondary products – for example, tallow and leather from cattle; pork from pigs; linen from flax; bread, beer, and basketry from grain. Some of these value-added products were then traded and exchanged at a profit, producing further government income; other were redistributed as payment to state employees, thereby funding the court and its projects. The remaining portion of agricultural produce (mostly grain) was put into storage in government granaries, probably located throughout Egypt in important regional centers. Some of the stored grain was used in its raw state to finance court activities, but a significant share was put aside as emergency stock, to be used in the event of a poor harvest to help prevent wide-spread famine.

The nomarchs of the Middle Kingdom cooperated fully with the king in sending resources, and this was largely because their autonomy was now respected by the throne in a way it had not been previously. Art during the Middle Kingdom period shows a much greater variation than that of the Old Kingdom which suggests a greater value placed on regional tastes and distinct styles rather than only court approved and regulated expression. Further, letters from the time make clear that the nomarchs were accorded a respect by the 12th Dynasty kings, which they had not known during the Old Kingdom. Under the reign of Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE) the power of the nomarchs was decreased and the nomes were reorganized. The title of nomarch disappears completely from the official records during Senusret III’s reign suggesting that it was abolished. Provincial rulers no longer had the freedoms they had enjoyed earlier but still benefitted from their position; they were now just more firmly under the control of the central government.

The 12th Dynasty of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (c. 2040-1802 BCE) is considered the ‘golden age’ of Egyptian government, art, and culture, when some of the most significant literary and artistic works were created, the economy was robust, and a strong central government empowered trade and production. Mass production of artifacts such as statuary (shabti dolls, for example) and jewelry during the First Intermediate Period had led to the rise of mass consumerism which continued during this time of the Middle Kingdom but with greater skill producing works of higher quality. The 13th Dynasty (c. 1802-c. 1782 BCE) was weaker than the 12th. The comfort and high standard of living of the Middle Kingdom declined as regional governors again assumed more power, priests amassed more wealth, and the central government became increasingly ineffective. In the far north of Egypt, at Avaris, a Semitic people had settled around a trading center and, during the 13th Dynasty, these people grew in power until they were able to assert their own autonomy and then expand their control of the region. These were the Hyksos (‘foreign kings’) whose rise signals the end of the Middle Kingdom and the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt.