A famous story from Greece relates how a young woman named Agnodice wished to become a doctor in Athens but found this forbidden. In fact, a woman practicing medicine in Athens in the 4th century BCE faced the death penalty. Refusing to give up on her dreams, she traveled to Alexandria where women were routinely allowed in the medical profession. Once she had received her training, she returned to Athens to practice but did so disguised as a man. When she was found to be a woman ‘pretending’ to be a doctor she was brought to trial charged with a capital crime until she was saved by her female patients who stormed the proceedings and shamed the prosecuting males into releasing her.

Following Agnodice’s trial, the laws were changed in Athens so women could now practice medicine, but by this time, female physicians were known in Egypt for centuries. The evidence for women in the medical field in Egypt, however, has been largely ignored by historians for the past century. Even so eminent an Egyptologist as Barbara Watterson claims that physicians in Egypt “were all, with one or two exceptions, male” (46). This claim, and others like it, flatly ignores evidence of women in the medical profession going back to the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 – c. 2613 BCE) when Merit-Ptah was the royal court’s chief physician c. 2700 BCE. Merit-Ptah is the first female doctor known by name in world history, but evidence suggests a medical school at the Temple of Neith in Sais (a city in Lower Egypt) run by a woman whose name is unknown c. 3000 BCE.

Egyptian Value of the Feminine

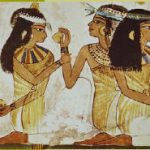

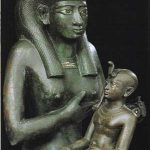

Female physicians do not appear in Egyptian history as frequently as males, and there is no doubt that men dominated the medical field. This does not mean, however, that there were no female doctors nor should it seem at all strange to find women in the medical profession in ancient Egypt. Women were highly respected throughout Egypt’s history, and feminine symbols appear early. Scholars identify the symbol of the tjet or tyet (also known as ‘The Knot of Isis’ or ‘Blood of Isis’ and dating from the Old Kingdom (c. 2613 – c. 2181 BCE) as the feminine counterpart to the ankh (dating from the Early Dynastic Period), and many of the major deities of the Egyptian Pantheon were female.

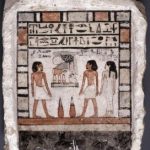

Neith is one of the most ancient goddesses in the world and among the earliest worshiped in Egypt. She is associated with creation in some myths and with the invention of birth as well as being linked with war, death, and the afterlife. One of the most popular and influential myths of Egypt is the story of Osiris and Isis in which Isis plays the dominant role. The goddess Hathor, presiding over joy, festivities, fertility, and many other bright aspects of life, was worshiped by both sexes as was Bastet, keeper of the hearth, home, and women’s secrets. Of the four deities most commonly associated with healing (Heka, Sekhmet, Serket, and Nefertum) two are female. The god Sobek, though also linked with healing, was more closely associated only with the aspects of surgery. The deity who presided over writing was the goddess Seshat, who was also the librarian of the gods. The recurring motif of the Distant Goddess in Egyptian myth, in which transformation is realized, is obviously associated with the feminine, and goddesses such as Qebhet and Nephthys play important roles in the mortuary rituals and the afterlife. The most important cultural value of Egyptian civilization was harmony and balance, symbolized by the goddess Ma’at and her white ostrich feather.

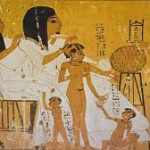

Egyptian culture is infused with feminine power and women were accorded almost equal rights and standing. Women could own land, initiate divorce, own businesses, and become priestesses and scribes. Doctors were all scribes, one of the most respected and affluent of the social classes, though not all scribes became doctors. Even though there persist scholars in the present day who claim women were not allowed to become scribes, the established female presence in the medical profession – as well as other evidence – argues otherwise. Doctors needed to be able to read the medical texts and spells as well as write them in order to care for their patients who were prone to a variety of illnesses.