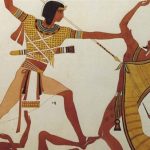

The Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE) is the era following the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-c.1069 BCE) and preceding the Late Period (c.525-332 BCE). Egyptian history was divided into eras of ‘kingdoms’ and ‘intermediate periods’ by Egyptologists of the late 19th century CE to clarify the study of the country’s history, but these designations were not used by the ancient Egyptians themselves. The term ‘kingdom’ is used to define an era of strong central government while ‘intermediate period’ designates a time of disunity and divided rule. In the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) and the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1570 BCE) this division caused tension between the two seats of power. In the First Intermediate Period relations were strained between the two kingdoms of Herakleopolis and Thebes, and during the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt between Thebes and the Hyksos rulers of Avaris, to the north, and the Nubians to the south.

THE Division of Power

In the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt, power was held almost equally between Tanis and Thebes early on, fluctuating at times one way or another, and the two cities ruled jointly even though they often had quite different agendas. Tanis was the seat of secular rule while Thebes was a theocracy. As there was no separation between one’s religious and daily life in ancient Egypt, ‘secular’ should be understood here along the lines of ‘pragmatic.’ The rulers of Tanis made their decisions based upon circumstances and accepted the responsibility even though the gods were certainly consulted. The High Priests at Thebes consulted the god Amun directly on every aspect of rule, and, in fact, Amun could safely be considered the actual ‘king’ of Thebes.

The king of Tanis and the High Priest of Thebes were often related as were those of the two ruling houses. The position of God’s Wife of Amun, a position of great power and wealth, illustrates this clearly as both daughters of the rulers of Tanis and Thebes held it. Joint projects and policies were undertaken by both cities, as evidenced by inscriptions left by the kings and priests, and each understood and respected the legitimacy of the other.

With this in mind, it is important to note that the Third Intermediate Period has long been regarded as a kind of epilogue to Egyptian history and an even darker age of chaos and collapse than the earlier intermediate periods. None of the intermediate periods of Egypt were as chaotic as early Egyptologists (and even later ones) interpreted them. The views of these early scholars were very much influenced by their times and the form of government they recognized as legitimate. Strong central rule was interpreted as good while disunity was seen as perilous. In reality, all three of the intermediate periods maintained a continuity of culture without a unifying central government and each added their own contributions to Egypt’s history.

Map of the Third Intermediate Period

The difference between the first two and the last is that, following the Third Intermediate Period, Egypt did not rise again to continue on to greater heights. In the latter part of the 22nd Dynasty, Egypt was divided by civil war, and by the time of the 23rd, the country was divided between self-styled monarchs who ruled from Herakleopolis, Tanis, Hermopolis, Thebes, Memphis, and Sais. This division made a united defense of the country impossible and the Nubians invaded from the south.

The 24th and 25th dynasties saw unification under Nubian rule, but the country was not strong enough to resist the advance of the Assyrians first under Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) in 671/670 BCE and then by Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE) in 666 BCE. Although the Assyrians were driven from the country, Egypt did not have the resources to repel other invaders. The Persian invasion of 525 BCE ended Egyptian autonomy until the rise of the 28th Dynasty of Amyrtaeus (c.404-398 BCE) in the Late Period freed Lower Egypt from Persian domination. Amyrtaeus, however, did not unify the country under Egyptian rule and the Persians continued to hold Upper Egypt. The 30th Dynasty (c. 380-343 BCE), also of the Late Period of Egypt, did achieve unity but it did not last long and the Persians returned in 343 BCE to hold Egypt as a satrapy until it was taken by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE. This period, therefore, is generally seen as a long decline which extinguished Egyptian culture, and while that interpretation is understandable, it is not quite accurate.

The Nature of the Third Intermediate Period

This difference between the Third Intermediate Period and the first two has resulted in a number of scholars, from the 19th through the 20th centuries CE and even to the present, characterizing the era as the end of Egyptian history and the collapse of the culture. The previous two intermediate periods have also been presented as ‘dark ages’ of confusion and chaos, but the Third Intermediate Period receives the worst treatment because there was no glorious Middle Kingdom or New Kingdom which followed it, only the Late Period which is often seen as simply a continuation of the Third Intermediate Period’s decline. These interpretations do a great disservice to an era which, although lacking in the traditional unity and homogeneity of the earlier periods, still maintained a strong sense of culture.

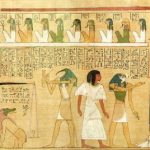

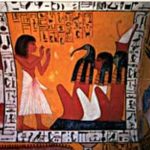

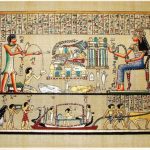

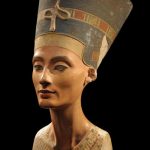

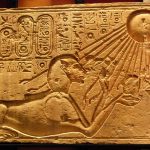

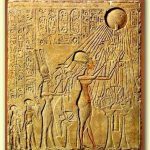

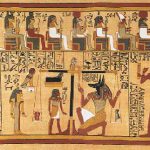

Egyptian mortuary rites, which resulted in some of the most impressive works of art for upper class and royal tombs, continued to be observed. Artwork of striking detail and innovation, especially in bronze, faience, silver, and gold, was produced during this time as well as intricate inscriptions, paintings, and statuary. Building projects were minimal during this time both in number and scope because the resources and a central government able to organize large-scale projects were not available until the reign of Amasis (Ahmose II, 570-526 BCE) of the 26th Dynasty and then the later unification of the country under the 30th Dynasty.

Religious practices seem to have focused on the concept of the pharaoh as a son of god, which led to the development of the mammisi (birth house), a local temple dedicated to worship of the child god born of the union of two powerful deities, one of whom was usually associated with the sun. The concept of triads of gods (father, mother, child) had a long history in Egypt and continued during this time with the popularity of the Cult of Isisand the triad of Osiris, Isis, and the child-god Horus. Worship of Amun, especially at Thebes, continued, but the Cult of Isis would outlast Amun’s worship and later travel to Rome to influence the early faith of Christianity.