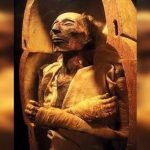

After its ‘golden age’ during the Twenty-first Dynasty and shortly after, the standard and quality of mummification steadily and gradually declined. However, the practice did not completely disappear until Muslim Arabs conquered Egypt in AD 641.

Mummification Elsewhere

It seems as though mankind has a subconscious need or desire to preserve the bodies of dead heroes. Alexander the Great was preserved in ‘white honey which had not been melted’, the English preserved their naval hereo, Lord Nelson, in brandy, and more recently the Communist countries have preserved the bodies of Lenin and Mao Tse-Tung.

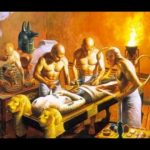

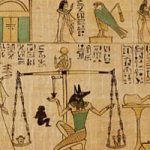

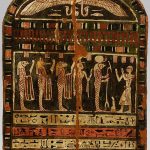

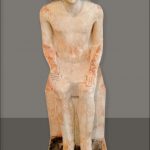

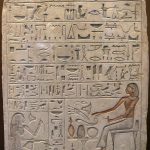

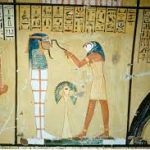

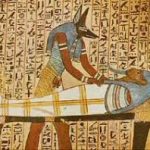

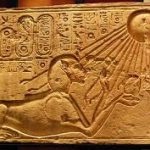

Religious Significance

The religious significance the ancient Egyptians attached to the art of mummification was based upon the belief that their god Osiris had been preserved by the gods from decaying after his death until they later restored him to life once more. By associating their dead kings with this god, the Egyptians believed that they, too, would be restored to life at some time in the future.

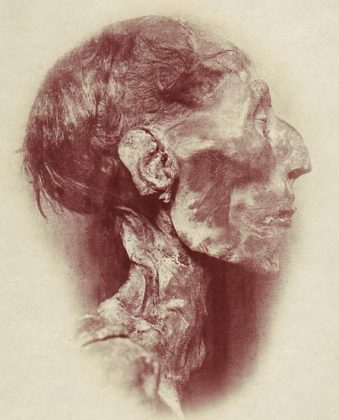

Ramesses II

In 1976, the mummified corpse of Ramesses II was flown to Paris to undergo cobalt-60 radiation treatment in an attempt to kill the airborne fungi that had penetrated the mummy’s showcase and was threatening to destroy the well-preserved body. Having been successfully cured of what has been termed its ‘museum illness’, the Pharaoh’s mummy was later returned to its ‘home’ in Egypt’s Cairo Museum. Who among those priests, busily preserving the body of their dead Pharaoh soon after his death in 1225 B.C., could have ever imagined that?

The lengths to which the modern world was prepared to go in order to keep the mummy intact demonstrates something of the fascination that this aspect of Egyptian civilization has held for the world since the mummies were rediscovered during Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt in 1798.