Children were considered a blessing in ancient Egypt. Sons and daughters took care of their parents in their old age. They were often called “the staff of old age,” that is, one upon whom the elderly parents could depend upon for support and care. The scribe Ani instructed that children repay the devotion of Egyptian mothers:

“Repay your mother for all her care. Give her as much bread as she needs, and carry her as she carried you, for you were a heavy burden to her. When you were finally born, she still carried you on her neck and for three years she suckled you and kept you clean.”

It was also expected that the older son or child carry on the funerary provisioning of the parents after their death. Children had value in ancient Egypt. The Greeks, who were accustomed to leaving infants exposed to the elements, were stunned to observe that every baby born to Egyptian families were cared for and raised. This care was not easy. Many children died to infection and disease. There was a high rate of infant mortality, one death out of two or three births, but the number of children born to a family on average were four to six, some even having ten to fifteen.

The Kahun, Berlin and Carlsberg papyri contain an extraordinary series of tests for fertility, pregnancy and to determine the sex of the unborn child. These tests cover a wide range of procedures, including the induction of vomiting and examination of the eyes. Perhaps the most famous test says: to see if a woman will or will not bear a child. Emmer and barley, the lady should moisten with her urine every day, like dates and like sand in two bags. If they all grow, she will bear a child. If the barley grows it will be a male, if the emmer grows it will be a female, if neither grow she will not bear a child.

This technique was tested in the late 20th century, and it showed no growth of either seed when watered with male or non-pregnant female urine. With forty specimens from pregnant women, there was growth of one or both species in more than 50% of the cases. While this seemed a good indicator of pregnancy, no growth failed to exclude pregnancy in 30% of the cases. When only one species germinated, the prediction of gender was correct in seven cases, and incorrect in sixteen cases.

Other pregnancy tests involve examination of the blood vessels over the breasts, and making mixtures to be drunk. In the former, the woman lies down, and her breasts, both arms and shoulders, are smeared with new oil. Early in the morning she is to be examined, and if her blood vessels look fresh and good, none being collapsed, that is, sunken, bearing children will occur. If the vessels are green and dark, she will bear children late. If a woman was given milk from one who had already borne a male child, and the milk was mixed with melon puree, if it made the woman sick, she was pregnant.

As there were ways of determining if a woman could bear children, so too were there ways believed to prevent pregnancy. Contraception was known, one suggested mixture involving acacia, carob, dates, all to be ground with honey and placed in the womans vagina.

Giving birth could also be a difficult and often dangerous process. In the tomb of King Horemheb at Saqqara were the fragmented remains of his queen Mutnodjmet, who was between the ages of 40 and 45 when she died. Among those remains were found the tiny bones of a fully developed fetus. Perhaps the queen had died in childbirth, as her pubic bones bore signs of previous difficult deliveries.

One spell to assist the birth-process went like this: “Come down, placenta, come down! I am Horus who conjures in order that she who is giving birth becomes better than she was, as if she was already deliveredLook, Hathor will lay her hand on her with an amulet of health! I am Horus who saves her!” This was to be repeated four times over a dwarf of clay, a Bes-amulet, placed on the brow of the woman in labor.

Ancient Egyptians estimated the time of gestation from 271 to 294 days, compared from the modern count of 282 days from the onset of the last cycle. The Egyptians believed that the uterus opened into the abdominal cavity, but also, that the alimentary canal coming from the mouth also connected with the uterus and the abdominal cavity. They believed that the monthly cycle ceased during pregnancy because the blood was being diverted to create and sustain the embryo.

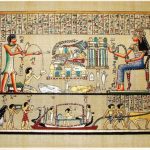

The medical papyri say nothing about the normal conduct of labor, and only representations of the magical birth of kings exist, as in the Westcar Papyrus. “Isis placed herself in front of [the woman], Nephthys behind her, and Heqet hastened the birth.The child rushed forth into [Isiss] arms, his bones strongthen they washed him and his umbilical cord was cut. He was placed in cloth on a couch of brick.”

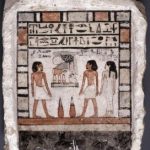

Delivery took place in special surroundings, on the cool roof of the house, or in an arbor or confinement pavilion, a structure of papyrus-stalk columns decorated with vines. A mattress, headrest, mat and cushion and a stool were arranged in the area. At delivery, only female helpers were present, not physicians. The peasant women called two women either from their households or neighbors, and wealthier classes would have servants and nurses present. There are no known words in ancient Egyptian for midwife, obstetrician, or gynecologist.

Women delivered their babies kneeling, or sitting on their heels, or on a delivery seat. This was indicated even shown in the birth hieroglyphic. Often, hot water was placed under the seat, so that the vapors would ease delivery. Delivery sayings were repeated, such as one that asked Amun to “make the heart of the deliverer strong, and keep alive the one that is coming.”

As in all areas of daily life, the gods of Egypt were connected to the birth process. The creator-god Khnum gave health to the newborn after birth. Women would place two small  statues for the gods Bes and Taweret. The dwarf-god Bes was supposed to vanquish any evil things hovering around the mother and baby. The chief deity of women in pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding, was the pregnant hippopotamus-goddess Taweret, often carrying a magic knife or the knot of Isis. To seek divine help in the birthing process, women often placed a magic ivory crescent-shaped wand, decorated with carvings of deities, snakes, lions, and crocodiles, on the stomach of the woman giving birth. About 150 of these wands have been found, all dating from the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period.

statues for the gods Bes and Taweret. The dwarf-god Bes was supposed to vanquish any evil things hovering around the mother and baby. The chief deity of women in pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding, was the pregnant hippopotamus-goddess Taweret, often carrying a magic knife or the knot of Isis. To seek divine help in the birthing process, women often placed a magic ivory crescent-shaped wand, decorated with carvings of deities, snakes, lions, and crocodiles, on the stomach of the woman giving birth. About 150 of these wands have been found, all dating from the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period.

The god Thoth was also often called upon for help, and the goddess Hathor, guardian of women and domestic bliss, was believed to be present at every birth. Severe labor pains might be soothed by the god Amun, gently blowing in as a cool northern breeze.

The Ebers Papyrus contains a remedy for contracting the uterus, but it is not clear as to whether this was to hasten birth, expel the placenta, or to return the uterus to pre-pregnancy size. The remedy went like this: mix the kheper-wer plant (identity now unknown), honey, water of carob, milk, strain and place in the vagina.

If the perineum had an injury during birth, the Kahun Papyrus contained this remedy: prepare new oil to be soaked into her vagina.

The Egyptians were always anxious to now the future, and in order to ascertain the destiny of new-born children they relied upon the seven Hathors, who hovered over a childs cradle and announced his destiny. Representations of these seven forms of the goddess appear in the tomb of Queen Nefertari and in various versions of the Book of Coming Forth by Day.

If a sickly baby was thought likely to die, its chances were assessed by the strength of its cries and its facial expression. A child that cries “Hii” will live, but one that cries “Mbi” will die. If the child made a sound like the creaking of the pine trees, or turned his face downward, he would die. Where there was still doubt, the infant was for three days put on a diet of milk containing a ground fragment of its placenta. If it did not vomit, it would survive.

The parents would lose no time in giving their child a name. Some Egyptians had very short names such as Ti or Abi, others had a complete phrase, such as Djedptahioufankh, meaning “Ptah says he will live.” Names may have pointed to physical qualities, such as Pakamen, the blind one, or to occupations, such as Pakapu, the birdcatcher.

Most parents liked to place their children under the sponsorship of some deity, and so there were children named Hori and others named Seti, and others named Ameni, that is, dedicated to Horus, to Set, and to Amun, respectively. The historian Manetho was under the protection of the Theban deity Montu. The name Mutemwia means “Mut is in her bark,” perhaps signifying that on the day of this girls birth, there was a procession of the goddess Mut, and the mother wanted to keep that special occasion by naming her daughter after the goddess.

Names could signify the gods pleasure, perhaps explaining why there were so many Amenhoteps, Khnumhoteps and Ptahhoteps, or, signify that the god was in front of or the father of the child, as in the name Amenemhat. Those with a name Siamun were children of the god Amun. Senwosrets name meant that he was a son of the early Theban goddess Wosret, thought to be the precursor of Mut as the consort of Amun.

After the child was named, the parents had to register it with the authorities. A princess Ahori, wife of one Nenoferkaptah, declared, “I gave birth to this baby that you see, who was named Merab and whose name was entered into the registers of the House of Life.” Births, marriages and deaths may have been recorded for inheritance and taxation purposes. When witnesses were called in legal proceedings, their names, those of their parents, and their occupation, were all noted.

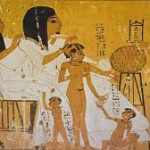

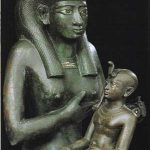

A baby stayed with its mother, carried in a sling around her neck. The mother, or a nurse, would nurse the baby for three years. Bottles, or at least the clay equivalents of bottles, have also been found.

The most common infant malady was infection of the alimentary canal. An example of a spell designed to ward off infection went like this: “Come on out, visitor from the darkness, who crawls along with your nose and face on the back of your head, not knowing why you are here! Have you come to kiss this child? I forbid you to do so! Have you come to do it harm? I forbid this! I have made ready for its protection a potion from the poisonous afat herb, from garlic which is bad for you, from honey which is sweet for the living but bitter for the dead.”

Some childrens mummies have been found to have a high incidence of stalled growth, possibly from malnutrition or infection. The young weaver called Nakht had signs of such arrested growth in his shin bones. Skin troubles like eczema, anemia, and tonsil infections, were also frequent. But rickets was virtually unknown in Egyptian children.

Amulets were often tied to each part of a childs body to protect it, with a different deity associated with a different body part. The crown of the head was the crown of Ra, the eyes the eyes of the Lord of the Universe, the ears are those of the Two Cobras, the arms those of the Falcon, etc. Protective spells were also written on small papyrus rolls, rolled up and bound in a pendant around the childs neck.

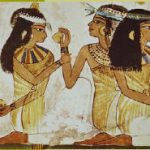

As children grew, they apparently had carefree periods in their lives. There have been many toys and games found in excavations, and paintings showing children playing together. The children wrestled, raced, played tug of war, used small doll-like figures of animals, boats, balls, and danced, just like children do today. They had birds or dogs for pets. Very young children often went naked, or with girdles around their waists. Their hair was worn in a braided plait, with the end rolled up in a curl, the familiar “sidelock” of youth.

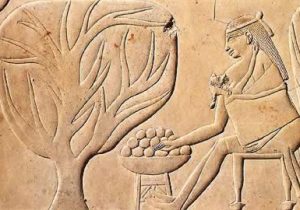

From about age five, the children began to help their families. Boys and girls of farmer families ran errands, fed animals, sowed seed, harvested and gleaned, fetched food for the workers, even finished pottery in the workshops. Older girls would begin to help in the kitchen, baking bread, and all children were responsible for caring for their younger siblings.

Children of wealthier families were taught how to manage their properties and estates, and boys may have been brought to scribal school. Boys were often brought in as apprentices to learn the duties of a bureaucrat or even of priesthood. Children of course learned by copying their parents and other adults. Children played military war games, and learned the ritual gestures of mourning, by watching their parents.

Later on, upper-class boys would go to scribal school and learn how to serve in the temple. In the New Kingdom and later, girls served in the temples as musicians and dancers. There may have been female scribes, though not much evidence for that exists. But girls did learn about their legal rights in property and business. It was clear that women understood about inheritance and property.

As boys and girls reached their teens, marriage was often considered as the next step in their lives. Boys would have been circumcised sometime after they reached the age of ten, and girls were often considered marriageable by thirteen. Once a young man and woman married, the cycle of life would begin again.