The First Intermediate Period has long been characterized as a time of chaos and darkness and artwork from this era has been used to substantiate such claims. The argument from art rests on an interpretation of First Intermediate Period works as poor quality as well as an absence of monumental building projects to prove that Egyptian culture was in a kind of free fall toward anarchy and dissolution. In reality, the First Intermediate Period of Egyptwas a time of tremendous growth and cultural change. The quality of the artwork resulted from a lack of a strong central government and the corresponding absence of state-mandated art.

The different districts were now free to develop their own vision in the arts and create according to that vision. There is nothing ‘low quality’ about First Intermediate Period art; it is simply different from Old Kingdom artwork. The lack of monumental building projects during this time is also easily explained: the dynasties of the Old Kingdom had drained the government treasury in creating their own grand monuments and, by the time of the 5th Dynasty, there were no resources left for such projects. The collapse of the Old Kingdom following the 6th Dynasty certainly was a time of confusion, but there is no evidence to suggest the era which followed was any kind of ‘dark age’.

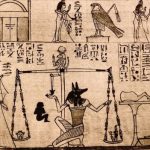

The First Intermediate Period produced a number of fine pieces but also saw the rise of mass-produced artwork. Items which had previously been made by a single artist were now assembled and painted by a production crew. Amulets, coffins, ceramics, and shabti dolls were among these crafts. Shabti dolls were important funerary objects which were buried with the deceased and were thought to come to life in the next world and tend to one’s responsibilities. These were made of faience, stone, or wood but, in the First Intermediate Period, are mostly of wood and mass produced to be sold cheaply. Shabti dolls were important items because they would allow the soul to relax in the afterlife while the shabti did one’s work. Previously, only the wealthy could afford shabti dolls, but in this era, they were available to those of more modest means.

Middle Kingdom Art

The First Intermediate Period ended when Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) of Thebesdefeated the kings of Herakleopolis and initiated the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). Thebes now became the capital of Egypt and a strong central government again had the power to dictate artistic taste and creation. The rulers of the Middle Kingdom, however, encouraged the different styles of the districts and did not mandate that all art conform to the tastes of the nobility. Although there was great reverence for Old Kingdom art and, in many cases, an obvious attempt to reflect it, Middle Kingdom Art is distinctive in the themes explored and the sophistication of the technique.

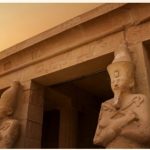

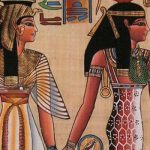

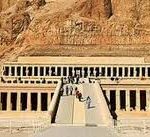

The Middle Kingdom is usually regarded as the high point of Egyptian culture. The tomb of Mentuhotep II is itself a work of art, sculpted from the cliffs near Thebes, which merges seamlessly with the natural landscape to create the effect of a wholly organic work. The paintings, frescoes, and statuary which accompanied the tomb also reflect a high level of sophistication and, as always, symmetry. Jewelry was also refined greatly at this time with some of the finest pieces in Egyptian history dated to this era. A pendant from the reign of Senusret II (c. 1897-1878 BCE) which he gave to his daughter is fashioned of thin gold wires attached to a solid gold backing inlaid with 372 semi-precious stones. The statues and busts of kings and queens are intricately carved with a precision and beauty lacking in much of the Old Kingdom artwork.

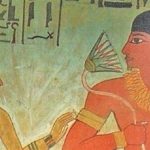

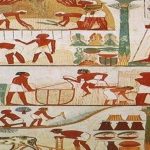

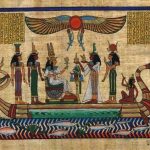

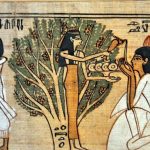

The most striking aspect of Middle Kingdom art, however, is the subject matter. Common people, instead of nobility, feature more often in art from this period than any other. The influence of the First Intermediate Period continues to be seen in all the art from the Middle Kingdom, where laborers, farmers, dancers, singers, and domestic life receive almost as much attention as kings, nobles, and the gods. Artwork in tombs continued to reflect the traditional view of the afterlife, but literature from the time questioned the old belief and suggested that one should concentrate on the only life one could be sure of, the present.

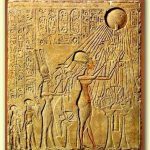

This emphasis on life on earth is reflected in less idealistic and more realistic artwork. Kings like Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE) are depicted in statuary and art as they really were instead of as ideal kings. Scholars recognize this by the uniformity and detail of the representations. Senusret III is seen in different works at different ages, sometimes looking careworn, sometimes victorious, whereas kings of earlier eras were always shown at the same age (young) and in the same way (powerful). Egyptian art is famously expressionless because the Egyptians recognized that emotions are fleeting and one would not want one’s eternal image to reflect only one moment in life but the totality of one’s existence.

Middle Kingdom art adheres to this principle while, at the same time, hinting more at the subject’s emotional state than in earlier eras. However the afterlife was viewed at this time, the emphasis in art always gravitates to the here-and-now. Images of the afterlife include people enjoying the simple pleasures of life on earth like eating, drinking, and sowing and harvesting a field. The detail of these scenes emphasizes the pleasures of life on earth, which one should make the most of. Dog collars during this time also become more sophisticated which suggests more leisure time for hunting and greater attention to the ornamentation of simple daily objects.

The Middle Kingdom began to dissolve during the 13th Dynasty when the rulers had grown too comfortable and neglected the affairs of state. The Nubians encroached from the south while a foreign people, the Hyksos, gained a substantial foothold in the Delta region of the north. The government at Thebes lost control of large sections of the Delta to the Hyksos and could do nothing about the growing power of the Nubians; it became increasingly obsolete and ushered in the era known as the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 – c. 1570 BCE). During this time the government at Thebes continued to commission artwork but on a smaller scale while the Hyksos either appropriated earlier works for their temples or commissioned for grander works.